There was a low rumble as the engine of the plane started. I felt the body of the airplane moving. People looked scared and worried. They all seemed to feel anxious…. There was a deep chill along my spine, it prickled and made me feel uneasy. The windows on the side of the plane showed dark outlines of houses. Rain dotted the windows. The rough seats that welcomed us were all the same size. I sat in an empty seat and looked out the window. Behind me on the ceiling was a dim light that would flicker gently. We were speeding down the runway. Outlines of people were illuminated by the occasional flashing thunder. All of a sudden I felt an upward motion and we were speeding up up up to America. At the end of the trip, I saw the tops of buildings and we got off. I was glad my feet were finally on solid ground. As I stepped out, I realized I was going to encounter miracles and opportunities that were clearly unthinkable.

– Christopher, 4th Grade

When I was young, all of my friends kept diaries. They were private, miniature books with fragile locks and keys that were hidden somewhere easy to find. They were a place to confess, grieve, exult, and record the thoughts that could not be shared—especially with adults. These diaries weren’t meant to be read, but somehow they always were. Then, the horror of your mother knowing about your first kiss, and if you had a nosy brother, the next thing you knew, the whole block knew your business. But who can blame them? Diaries are tempting, and it takes a parent of supreme willpower to keep the covers closed when he or she comes across a journal with “Dear diary” scribbled across the front page. Children aren’t immune to diaries’ enticements either (remember the nosy brother?), and teachers can draw on this desire constructively to promote reading and writing.

One of the many beauties of diaries lies in the fact that they record not only a personal story but the larger story of a people. When I was looking for children’s diaries to use in the classroom, I compiled a rich compendium of confessional youth writing: a collective diary written by children in a Japanese internment camp, the diary of Charlotte Forten (a free African American child living in Salem in 1850), and the diary of William Bircher (a Civil War drummer boy).1 I also discovered an unlikely source: the journals of the young Anaïs Nin. Nin’s adolescent writings are remarkable in their attention to sensory detail and their passionate exploration of life—never more so than in the following account of her moment of arrival in America at the age of ten.

One of the many beauties of diaries lies in the fact that they record not only a personal story but the larger story of a people. When I was looking for children’s diaries to use in the classroom, I compiled a rich compendium of confessional youth writing: a collective diary written by children in a Japanese internment camp, the diary of Charlotte Forten (a free African American child living in Salem in 1850), and the diary of William Bircher (a Civil War drummer boy).(1) I also discovered an unlikely source: the journals of the young Anaïs Nin. Nin’s adolescent writings are remarkable in their attention to sensory detail and their passionate exploration of life— never more so than in the following account of her moment of arrival in America at the age of ten.

August 11, 1914

We were all dressed and on deck. It was 2 o’clock and one could vaguely see a city, but very far away. The sea was gray and heavy. How different from the beautiful sea of Spain! I was anxious to arrive, but I was sad. I felt a chill around my heart and I was seeing things all wrong. Suddenly we were wrapped in a thick fog, torrential rain began to fall, thunder rumbled; lightning flashes lit the heavy black sky. None of the Spanish passengers had ever seen weather like that, so the frightened women wept and the men prayed in low tones. We were not afraid. Maman had seen many other storms and her calmness reassured us. We were the first to go back up on the wet deck. But the fog continued and we waited. It was 4 o’clock when the ship began to move again, slowly as though she approached the great city with fear. Now, leaning on the railing, I couldn’t hear anything. My eyes were fixed on the light that drew closer. I saw the tall buildings. I heard the whistling of the engine. I saw a great deal of movement. Huge buildings went by in front of me. I hated those buildings in advance because they hid what I loved most—flowers, birds, fields. (2)

At the time I came upon this excerpt, I was teaching a class of precocious fourth graders in Queens. It was a happy coincidence (the luck factor in teaching) that the students were studying immigration. There were a few recent immigrants in the class, but the majority were second-, third-, and fourth-generation Americans. I started the class by asking, “Who here keeps a diary?” Some students raised their hands. “Would you let your mother read it?” Horrified answers: “No!” “Would you let me read it?” Some hesitation. “No!” “But do you like reading other people’s diaries?” “Yes!” “Well, today, I have a page from the diary of Anaïs Nin. She was a famous writer who came to America, to New York City to be exact, at your age. On the boat from Europe, she began her very first diary.”

After reading the excerpt, I started out with some simpler questions: “What is she feeling? Where is she coming from? What does she miss?” Then deeper questions: “How does the outer world reflect her inner world? How can you tell this is from a different time in history?” Then personal questions: “How would you feel if you had to move someplace far away, leave all your friends behind, and start a new life? Is there anyone here who came from a different country, or whose parents did?”

Most of the students raised their hands. “Russia, India, Italy, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Germany, Paraguay, Greece, Puerto Rico, Colombia, Afghanistan, Mexico….”

Then the big question: “Did your parents or grandparents ever tell you stories about when they first came?” They were shy, until I shared my story: “When my father first came here in 1970 (ancient history!), he didn’t know anybody and he only had $500. He was living in the YMCA and the first week he was here, someone stole all his money when he was asleep.”

There were gasps, giggles and then a flurry of stories. “My grandfather had money stolen too!” “My mother said when she came here she was scared of the subways!”

I told them that even if they didn’t know the details of their families’ arrivals, they could write from their imaginations. I had them close their eyes and visualize coming to this country for the first time. How did they get here? Was it a mode of transportation they were familiar with? What did they see when they looked around? Were there different animals and vegetation? Was the weather shockingly different than in their native land? When they opened their eyes, they began to write furiously. There is something freeing about writing in a diary, it is like you are cuddling up to a close friend whispering secrets in his or her ear. After about fifteen minutes, I told the class to wrap up their last sentence, but not to worry if they weren’t finished. We were going to continue working on our diary entries next time. I had two volunteers read their works-in-progress and sent them off with a series of questions to ask their families: Who was the first person to come to America? When did they come? Did they come alone? Did they know anyone here? What did they bring? What were they wearing? How did they feel?

When I saw them the next week, they were bursting with stories about their families. One boy, who had initially refused to do the assignment because he was adopted, came to me, his face glowing, with three sheets full of writing. His adopted mother had told him the story of his birth family, going three generations back.

Dear Diary,

I walked onto a large plane with a bottle of whiskey in one hand and a suitcase in the other. I looked back at my family for the last time. I started to cry rivers of tears. I waved at them and blew them a kiss. Now, it was raining heavy. I looked out the window, watching my family become smaller and smaller as the plane went higher and higher in the sky. The gray sky and rain was terrible. It made me feel even sadder than before. I closed my eyes, trying to sleep and stop crying. Finally, we landed. I woke up at 3 o’clock. My short-sleeve shirt and pants weren’t enough to keep me warm. I had forgotten that it was the middle of the winter and in Puerto Rico, it was never cold…. My uncle finally came to pick me up. The rain had stopped and now the sun was out. My uncle took me home. I was worried about my family in Puerto Rico. I was scared of the tall buildings and carriages that I saw. My family should have come. America is so different. It is so exciting and thrilling.

-Alyssa

It was 2 o’clock and I was on the plane. Below the plane, I spotted a new land, an unusual new land. It was different from Korea…. When I got off the plane, people were staring at me. So I decided to explore the new land. There was a building and a statue of a green lady holding a torch. I was wondering why there was a statue of a green lady. She was big. I saw many weird people. They had big noses and weird eyes. I didn’t know if I would fit in well. Soon I got my first baby sister! She is used to the building and the people. There were many other Koreans that fit in perfectly. Why do they have what I don’t?

-Angie

Notes

- The Children of Topaz: The Story of a Japanese-American Internment Camp. Based on a classroom diary by Michael O. Tunnell and George W. Chilcoat. A Free Black Girl Before the Civil War: The Diary of Charlotte Forten, 1854, edited by Christy Steele. A Civil War Drummer Boy: The Diary of William Bircher, 1861-1865, edited by Shelley Swanson Sateren.

- This excerpt appears in Meredith Sue Willis’s Personal Fiction Writing (T&W Books, 2000).

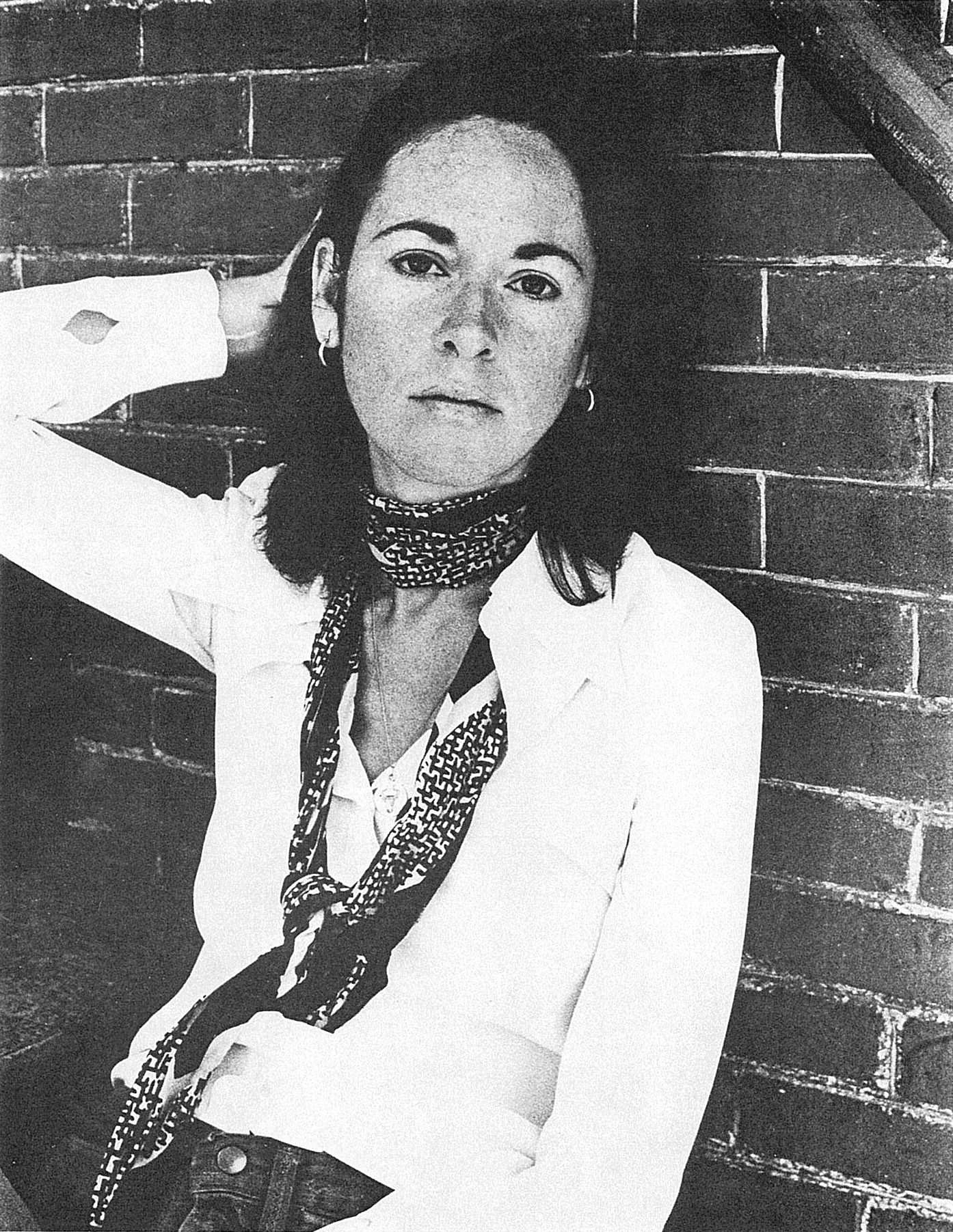

Rehman’s dark comedy, Corona, was chosen by the NY Public Library as one of its favorite books about NYC. She is co-editor of Colonize This! Young Women of Color on Today’s Feminism and author of the collection of poetry, Marianna’s Beauty Salon, described by Joseph O. Legaspi as “a love poem for Muslim girls, Queens, and immigrants making sense of their foreign home—and surviving.”

Her new novel, Roses, in the Mouth of a Lion, is a modern classic about what it means to be Muslim and queer in a Pakistani-American community.