Editors note: This interivew is from a 2004 issue of Teachers & Writers Magazine (2004, Vol. 36, No. 2).

Christina Davis: Last fall, you left Urban Word NYC (an after-school spoken word program based at Teachers & Writers) to take part in a national nonpartisan campaign called Declare Yourself. After an 18-city tour of colleges, at which you performed a spoken word show created specifically to “get out the youth vote,” I wonder how your thinking has changed? What were your initial assumptions about the relationship between poetry and politics, between self-expression and civic participation, and how have they altered?

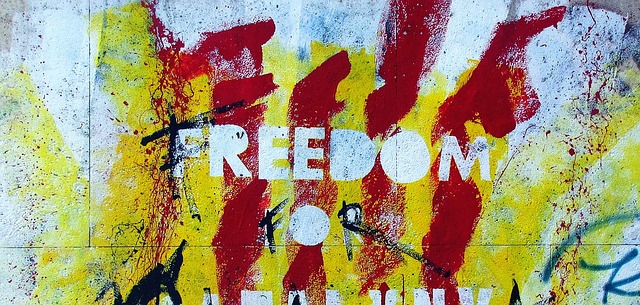

Marty McConnell: My thinking hasn’t changed much, except that I am more convinced than ever of the need for each of us to do everything we can to protect the freedom of expression in this country. I have always felt that poetry and politics are necessarily, and to some extent inextricably, interlaced. Poetry is the expression—the re-creation, if you will—of life in words, and our lives, like it or not, are political. One of the primary messages of this campaign is precisely that: You cannot escape the politics of your existence.

Self-expression is crucial to civic participation. Through this campaign, we have attempted to demonstrate the power of speaking your life, hoping that in seeing us speak, others will be moved to investigate and release the power of their own voices. And, of course, to vote. But not just to vote, but to see that act as a foundational event, the crucial expression of the self in American society. And from there, to go on speaking and dialoguing and listening and exploring what it means to be an American in our time.

CD: What does the verb “declare” mean to you? The Declaration of Independence is based on the pronoun “we”; whereas you seem to be inviting the “I” to declare itself. Do you think there is something about the anonymous nature of voting that makes it less attractive, less self-expressive, to teens? How have you sought to help youth see the relationship between self-expression and the ballot?

MM: To declare is to assert the self, to deliver to the world one’s specific and individual truth. For too long, too many of us have dismissed voting as a means of self-expression, choosing protest or poem or videogame playing over this basic and ultimately solitary act. We’ve declared ourselves through our clothes, our music, our hair, and overlooked this basic way in which we each can insist upon mattering to this country, can insist upon being heard.

So yes, we have tried throughout this campaign to illuminate for young people the connection between voting and self-expression. You can’t simply say “voting is important” and expect anything to happen. It’s like saying “peas are good for you” to a toddler; you’re still going to end up with a shirt full of spit green. Young people are smart, and getting smarter. They know what’s going on in the world, for better or worse. What we are saying is don’t count yourself out. Break the vicious cycle of politicians not speaking to young people because young people don’t vote, and conversely young people not voting because politicians don’t speak to them. Educate yourself, find your own reasons, and vote. Make them hear you.

We’re saying, you matter. Make sure your government knows that you know that. We’re saying, only you can silence yourself. Let all the knowledge and angst and opinion you carry drive you to the polls, to make yourself heard in this fundamental way.

CD: Prior to going on the road, you and your fellow spoken word artists met in L.A. to workshop the production. What kinds of exercises did you use?

MM: We created this show from scratch, starting in October of ’03 and continuing through today. From the beginning, we were committed to the idea of creating a multi-voice experience rather than a series of individual poems strung together.

We began each writing session by sharing relevant poems by people outside the group. We spent a great deal of time hashing out our own feelings about voting, civic participation, and the history of this country. We also discussed how we could present issues in a way that demonstrated their complexity, rather than persuading listeners to feel one way or another. One exercise involved each of us writing a series of assertions about the world and the nation, then placing each assertion in a bag and drawing them at random as writing prompts. A second involved each of us taking on one concept—equality, or justice, or dignity—and personifying it in a poem that examined what would happen should those concepts up and walk away. For example, the first line of mine was “Equality takes to the road with a bandanna tied to a stick.” My poem extrapolated upon what happens when we discover that this equality is hardly missed, since it is simply a synthetic version of the authentic one abandoned long ago.

CD: In Declare Yourself ’s mission statement, you repeat the phrases “authentic voices” and “authentic thoughts” several times. I wonder if you could talk about the nature of authenticity. Why it is so crucial to cultivate it at this time, and how it could be elicited in the classroom?

MM: We live in a time of rampant inauthenticity. Reality TV, videogames, and cybersex all conspire to create a false world, one that separates us from the breathing, bleeding, flawed, face-to-face life all around us. Which is why poetry, and its performance, is so crucial right now. Good poetry requires authenticity, disallows hiding and pretense. The act of voting is somehow poetic to me. So simple, such a clean concept: I, this one person, go into this little booth and say who I want making decisions about my life and my country. And having said it, I leave. Other people go in after I have had my say, and it’s all very civilized. The idea of all these people, these millions of people, knowing that they, whoever they are, have the right to decide, to choose based on whatever they think is right—no admissions exam, no SAT, no credit check, just a registration card they got in the mail. There’s more to it of course, all the politics swirling around, but it’s beautiful really, at base.

Authenticity requires exposure, vulnerability in a way. And that is not an easy thing to ask students to suffer, particularly marginalized students who have worked very hard to create buffer zones to protect themselves. But poetry allows a teacher a way in, a chance to show students examples of people just like them who do speak with authenticity, who express the truth of their lives and are applauded for it.

Teenagers in particular are hugely sensitive to inauthenticity; nothing rankles them more. For this reason, it’s crucial to introduce students to a variety of poets, from Quincy Troupe writing about Magic Johnson to Marie Howe ’fessing up to kissing girls at slumber parties for practice. In my experience, students honor an authentic poem whether or not it reflects their own experience, and the greater risks a poet takes in pursuit of that authenticity (the more vulnerable the poet allows herself to be), the more the students respond.

How do we get young writers to be authentic in their own work? Excellent examples are one way. Creating an atmosphere that is at once safe enough for vulnerability and challenging enough to encourage young people to engage in real dialogue about their lives and their work is another. Often it is the young people who can best point out the inauthenticity or the genuine portions of their peers’ poetry. And authenticity has to be valued publicly, and rewarded. The risk here is that at times young writers can get caught up in the facts of the experience they are trying to capture, and can limit themselves from exploring the truth of the poem, which might be very different from the facts. So a discussion of that point is crucial.

Christina Davis is the author of An Ethic (Nightboat Books, 2013) and Forth A Raven (Alice James Books, 2006). Her poems and essays have appeared in the American Poetry Review, At Length, Boston Review, The Concord Saunterer: A Journal of Thoreau Studies, The Occupy Wall Street Poetry Anthology, Poetry Magazine, and other publications. She worked for Teachers & Writers from 2001–2005 and currently serves as curator of the Woodberry Poetry Room, Harvard University. She wishes to dedicate her poem to Steve Shapiro and Nancy Larson Shapiro.