“All I have are Iggy Pop and dirt-biking before I got locked up,” one student shared with the class.

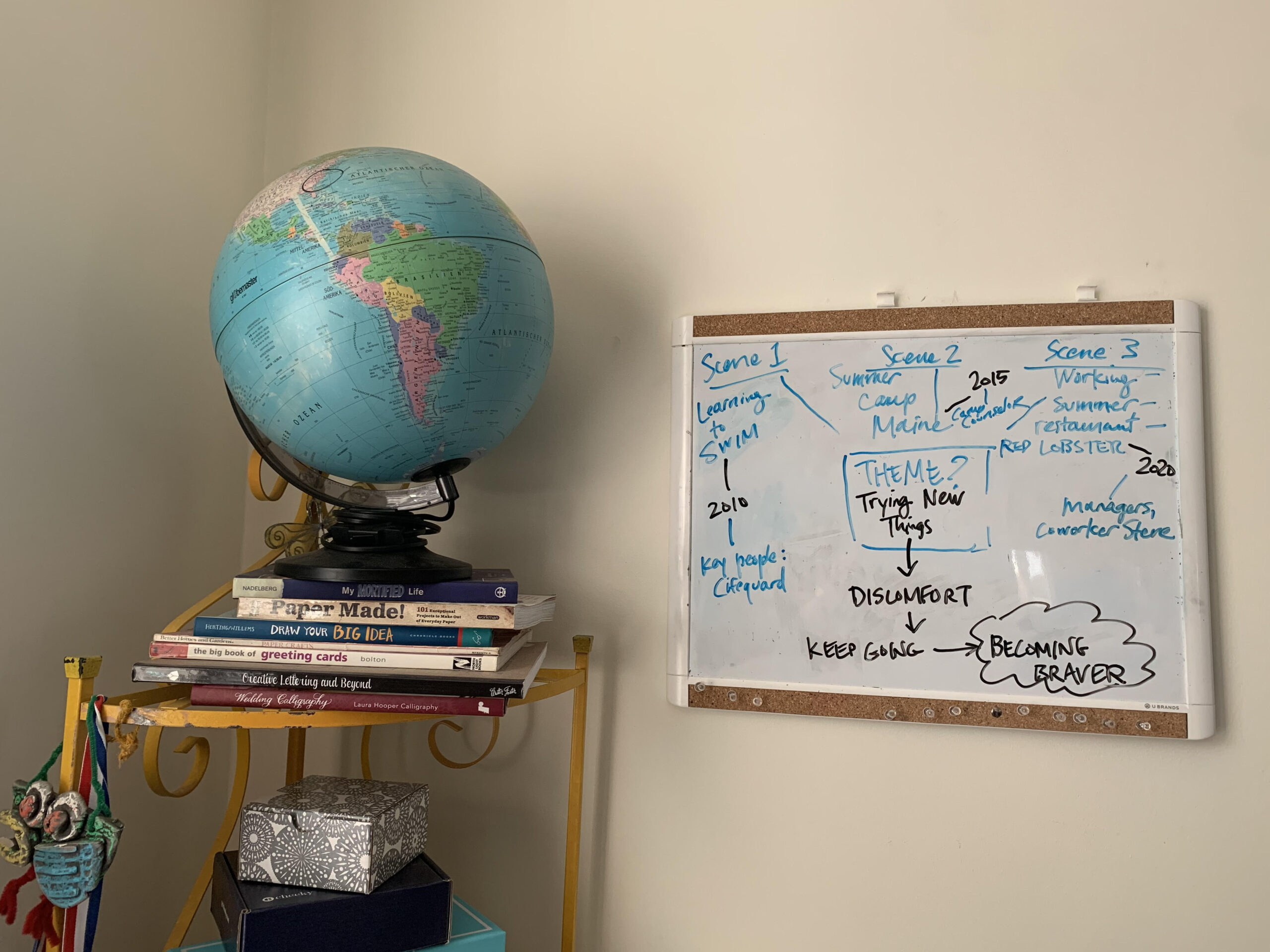

That sounds like plenty of material to me, I said, as I began to jot some of the student’s memories on the board.

First, I drew a large rectangle box in dry erase marker. I explained that this would be the core theme of what connects these memories — if, in fact, we found a connection. But first, we had to map out the time frame of the memories, the images that came from the memories, and the cast of characters present in the memories.

Extending from the main box, I drew spindly legs pointing in every direction.

“Each leg represents a singular memory, a slice of life,” I explained. This is the scaffolding upon which we build our work. This is how I help to usher my students toward the difficult work of memoir writing.

My student shared that he spent many seasons of his youth dirt-biking in rural areas with friends. He recalled some of the music that reminded him of these times. He also shared a specific memory of being chased by police officers because, he explained, these were not simply bicycles but rather motorized off-road bikes, not permitted on major byways, but that he and his friends dared to ride on the wide open road.

This particular student had experienced time behind bars and was in a pre-release program so that he could attend our class while he was serving the remainder of his sentence. As the student and I mapped out the memories of biking, police encounters, as well as his experience in prison, other students began to notice the themes. There were moments of freedom and childish shenanigans. There was also a price to pay for exercising these freedoms. Fun and frivolity can lead to crime and punishment.

It seemed that this student could better ascertain a theme — that of trading childhood for adulthood — from having shared the memories aloud, as well as seeing them written on a large canvas, with other classmates lending their own eyes and ears to the exercise. The student went on to write a memoir of which he was proud, threading in lyrics from various Iggy Pop songs that related to his story.

I have drawn a spiderweb on the dry erase board of so many college classrooms. Until I began working with a population of students largely from under-resourced neighborhoods, I never realized how powerful simple personal narrative exercises could be. While my students are mostly pursuing degrees in technical fields, many have shared with me that they never thought of themselves as writers until they attempted memoir writing. This exercise requires no prior knowledge of literature and does not require a mastery of language. It simply asks that the writer be willing to trace back to the people, places, and experiences that have shaped their lives.

“The spiderweb,” otherwise known as a non-linear visualization of interconnected memories and events from our lives, has been one of the most successful teaching methodologies in my English composition classes. I measure the success of this exercise by the number of students who have requested it, and how often they ask for extra worksheets as they are preparing to write their short memoirs. Semester after semester, students ask if I have any “extra spiderwebs.” This is not an original method by any means, but I find that my digital native students crave more tactile ways to work through their personal narratives. They scroll, scan, and swipe screens all day. The experience of pressing pen to paper, or scribbling on a big dry erase board, while not novel, seems to trigger something important for the students that they do not access in other spaces.

I teach at a technical institute in Boston where my students are mainly first-generation matriculants. Some have aged out of foster care and are learning to live independently for the first time. Others contend with poverty and the attendant instability that is so often part of the territory. Because of the instability and trauma many of my students have experienced, I take very seriously my responsibility as a teacher to shepherd them in writing their memoirs without triggering unresolved trauma.

The spiderweb knows some stories aren’t linear

An obvious approach to writing essays is to first identify a theme and to build a case full of evidence around that theme or thesis. But what if you’ve not yet processed the “evidence” of your own life? What if you have only learned to live with constant flux and the frequent need for flexibility, even around basic needs such as food, shelter, and clothing? Although I am not a mental health therapist, I know that processing our lives through writing can be helpful or hurtful. The spiderweb allows us to break down our thoughts and memories in a way that I hope is manageable for every student.

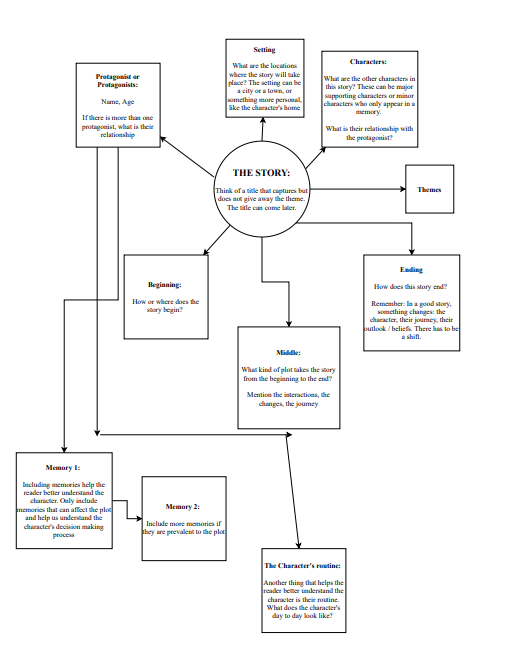

The spiderweb is a fairly rudimentary diagram of which I print a few copies for each student. I tell them that this is just for scribbling ideas down — nothing is in wet cement. First, I encourage students to try to think of a relationship or experience that was formative for them:

Is there a relationship that caused you to change your character or perspective?

Have you had an experience that changed your perspective on the world, or your opinion of yourself?

Did you work toward a goal and reach it or not reach it? What was that journey like and what was the destination?

Have you experienced something that friends often find interesting?

Once they have identified an experience or relationship that seems formative, I encourage them to write down memories in the “Memory” section at the top of the spiderweb. I remind the students that these memories may not seem exciting, but that they are still important—our memories may be trying to teach us something. The memories may be vivid or vague, and they can write down as much as they like. They don’t need to judge the memories, just to write down whatever comes to them.

Here is the basic form of the spiderweb:

We then try to identify the time frame in which the memories occurred, any sense memories (sights, sounds, smells) associated with the recollections, and the “cast” members that played major roles in these memories.

Once we look at our spiderwebs, sometimes students still feel lost about what the information represents. I tell students there is no need to rush to conclude anything, to draw any grand thesis statement. Sometimes they may want to walk with their memories for a bit, or to examine whether they see a pattern play out in other parts of their lives.

Even getting stuck, though, presents an opportunity with the spiderweb. Just as when one’s car winds up in a ditch, no one is getting that car out of the ditch by themselves. The same goes for our personal narratives. Sometimes we’re too close to the nature of our stories to see the metaphors and themes emerging.

When students get stuck

This is actually my favorite part of the exercise. I draw the spiderweb on the dry erase board and I invite a student to share with the class what they’re seeing emerge on their page.

In a recent class, one of my students shared that he was struggling. He felt bad about his memories. He loved his parents and knew they had tried hard in raising his family, but their early separation had been shattering for him. Yet, he didn’t want to shame his parents in his memoir. So I asked him if he would “reverse engineer” his memories. If he could start with his life today — how is his relationship with his parents now? Is there a recent memory that captures what the relationships are like? What does he hope for himself? That is, does he hope to have a family of his own one day? Then I encouraged him to work backward and to write down any memories of what it was like for him growing up with two different households, scrolling back to the day when he remembers his parents separating. I reminded him that this story was about him and not about his opinion of his parents. He was empowered to center himself in the action.

The student experienced a beautiful breakthrough and other students weighed in that they too knew what it was like to love their parents and also to have gone through family strife. The student said he had not written about his family before because he had feared assigning unfair judgment. By working backwards from recent history to deeper history, the student could be the protagonist of his own tale.

The final flourish in the spiderweb is when the students decide what their memoir is about. They write in the center of the memoir what they have concluded from what they have written upon the “threads”: their memoir is about them and their experience(s) — but mostly what they did as a result of those experiences. Using the spiderweb as our outline, the students are then better prepared to write their 2-4 page memoir in paragraph form.

The stories that have emerged have stunned me to breathless silence. One student who did not want to write his memoir, especially as it included his recent imprisonment, found one of the legs of his spiderweb was his devoted girlfriend. Writing about their relationship and the hope it sustained for him through his incarceration was uplifting for him, and he said it helped him to focus on the good in his life.

About the student who incorporated lyrics by Iggy Pop, a musical interest we both shared that I might not have known about otherwise, I truly believe the prolific songwriter himself may have known how I feel as the teacher of spiderwebs. I feel that I am both the driver of the vehicle, and once the students are able to access their threads, I become the passenger. To quote Mr. Pop:

“Oh, the passenger

He rides and he rides

He sees things from under glass

He looks through his window’s eye…

And all of it is yours and mine”

What a joy it is to help students access the stories that have shaped their lives, and in this way, they consistently shape mine.

Kendra Stanton Lee is an instructor of humanities at Benjamin Franklin Institute of Technology in Boston. Her essays have appeared in The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, Slate.com and others. She lives with her husband, their two children, and a wily rescue dog.