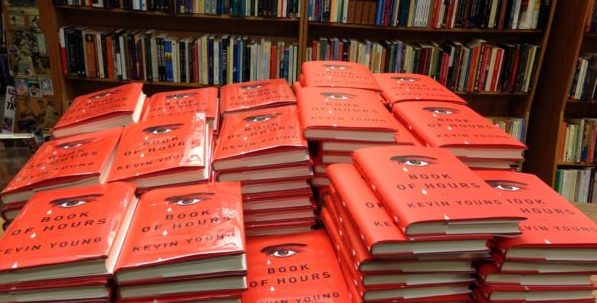

The Poetry of Kevin Young, says Lucille Clifton, ”re-creates for us an inner history which is compelling and authentic and American.” A National Book Award finalist, Young is the author of eleven books of poetry and prose, most recently Blue Laws: Selected & Uncollected Poems 1995-2015 (Knopf, 2016), longlisted for the National Book Award; Book of Hours (Knopf, 2014), a finalist for the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award and winner of the Lenore Marshall Prize for Poetry from the Academy of American Poets; and Ardency: A Chronicle of the Amistad Rebels (Knopf, 2011), winner of an American Book Award.

Young’s next nonfiction book, Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News, will be out from Graywolf Press November 14, 2017, and is longlisted for the National Book Award. Young’s nonfiction book The Grey Album: On the Blackness of Blackness (Graywolf Press, 2012) won the Graywolf Press Nonfiction Prize and the PEN Open Book Award; it was also a New York Times Notable Book for 2012 and a finalist for the 2013 National Book Critics Circle Award for criticism.

Young is the Director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, newly named a National Historic Landmark. We spoke in early June in the offices of Teachers & Writers Collaborative in New York City.

[Editors note: This interview was originally published in Teachers & Writers Magazine in 2009.]

Susan Karwoska: Your poetry reflects a broad range of interests: music, art, film, history. Did you ever consider following another path? How is it you chose to be a poet?

Kevin Young: I think that poetry chooses you. I don’t know if you choose it, exactly. It was the place I found where I could explore all these other things. History and music I think are two of poetry’s concerns. And, well, you have to be musical to be a musician. I took piano lessons, but I don’t play any instruments now; I can’t read music. I’m not a musical person. That said, my grandfather played zydeco music and I have his fiddle, so I feel like there’s this connection to music in my family, in my growing up. I think you just end up writing about the things around you, but also about the things you want to revisit and stay with. I’m not sure there’s much choice involved.

SK: Your work is very personal, but at the same time it situates you as an American in a certain time and place, and it’s interesting to me how these voices overlap in your work. When you write are you conscious of this, or does the personal automatically bring you to the larger concerns?

KY: Well, I don’t actually think about either of those things. I think that comes later. In the moment I think I’m just trying to get down the music of the poem. I mean, sometimes one is more conscious than others, but I find that my best poems, the poems I’m most invested in, the ones that come from that wellspring, not that they come easily, are from a place that is necessary and almost unspoken. My last book [Dear Darkness] has a lot of elegies, for instance, and it’s the kind of thing that you don’t really want to write but you have to. In For the Confederate Dead I have a long elegy called “African Elegy” written for a friend of mine who died. He was killed in a car accident on the one-year anniversary of September 11th, so I was really aware of this public grief mixed with this private grief, and the question of how to address both. In this case it was impossible to shut out the public grieving, the mourning, but mostly I wanted to describe it exactly right. If you’re worrying about all that other stuff you might not be crafting a poem.

SK: You lose the music.

KY: Yeah.

SK: Where did you grow up?

KY: I moved around a lot. My family’s from Louisiana, both sides of my family, but I was born in the Midwest, Nebraska, and moved about five times before I was ten. I lived in Boston, Chicago, Syracuse, and Boston again, and then we moved to Kansas, and that’s where I went to high school.

SK: When did you first start writing poems or think that you might want to be a poet?

KY: I came to poetry fairly young, I suppose, looking back on it. I was probably thirteen or so and I took a summer class in poetry with a guy who’s more of a fiction writer, Tom Averill, in Topeka, Kansas. We had to write both fiction and poetry in this class and I did both. Before then I’d always written little stories, but this was the first time I think I ever thought of writing a poem in this way and that it might be worthwhile to pursue. And if you wrote a poem that was at all successful he would pass it out to the class, and I remember the poem I wrote so it’s hard to imagine he thought it was successful…

SK: You were thirteen!

KY: But he would pass them out anonymously, which was amazing because it was almost more thrilling than if your name was on it, and I think that thrill sort of captured me. Looking back on it, when I wrote those little stories I was always worried about every word being right, so I think even then I had a poet’s temperament. I just started writing like crazy after that. I mean nothing good. I don’t think I thought of myself as a poet, though, until well into writing what would become my first book, years later. A lot of those poems were about my family and Louisiana, and a way of life in the rural South that was disappearing, it seemed. How do you capture these memories and this personal history? But I don’t think I was totally comfortable with this notion of being a poet because I didn’t know any poets. It wasn’t a job description in my family that was familiar. That said, my parents were always supportive, but I think they breathed a sigh of relief when I got a job as a professor, even though I already had a book out and everything. I think in a way that that uncertainty [about the life of a poet] spurred me just to write more, to get the thing done, because who knew if you could make a life this way? Then again, I didn’t have a choice but to write these stories that I would hear or invent or find about the idea of home, where home was and what it was about and how you could understand it. When I was young I thought everyone had the kind of childhood that I had. My parents had grown up the same way, and it wasn’t until I got to college that I realized that not everyone went to the South every summer and ate grits. In my latest book I return to that terrain and to food specifically as a way of talking about memory and borne and history. Like I said, I thought everybody had pepper vinegar, which is hot peppers with vinegar, in a jar in their fridge. You pour it on greens and spice things with it, and I thought everyone had that. So I was somewhat naive, I guess, but usefully so. When you grow up a certain way you don’t really think about it, but you treasure it maybe even a bit more when you find out how unique it is. I feel like every book of mine is trying to describe this, but it’s impossible to convey. For instance, on my father’s side of the family they’ve lived in the same parish on the same patch of land for so many generations; in fact, I think in that parish for maybe 200 years. And there are two cemeteries there, one for each side of my family, that are just filled with my relatives, going back a long time, a hundred years of graves, you know.

SK: Very few Americans have that

KY: I know. I paid a pilgrimage there last year. My father passed away, and going back to these places was very powerful.

SK: Can you describe your writing process? And when I ask this I mean not just the nuts and bolts of when and where and for how long you work when you sit down to write, hut also the less tangible parts of the process, how you get an idea and turn it into a poem on the page.

KY: I often start with a title or a line, or sometimes just a phrase bouncing around. Sometimes it will be a title that I just can’t get out of my head. For instance, I have a poem based on a song called “I am Trying to Break Your Heart.” I just love that title. And how do you write a poem that doesn’t reproduce the song, because that’s sort of cheating, but riffs off of it and goes somewhere else? With the poems in Jelly Roll, there’s a word like “juke,” for instance. That’s such a great word; how do you evoke that? Or sometimes in Jelly Roll, I’d write a poem…. There are these blues-based love poems, and I’d write one and then have to find a title that spoke to some of the concerns in the poem. In terms of process, I write by hand in a notebook first, or a scrap of paper, and depending on how that’s going I’ll put it onto the computer or type it up either sooner or maybe years later; then I’ll print it out and I’m constantly scrawling all over those, revising.

SK: Do you have a discipline of sitting down every day? Is it just when the inspiration strikes, or when you can get to it?

KY: Well, these days I’m busy enough that it’s usually when I can get to it. But if I am working on something long I’ll try to work on it every day for a certain time, as long as I can, really, but after about three or four hours you’re done, really. It’s hard to work past that. I used to write at night when I was younger, but I can’t do that anymore. I was just reading a biography of James Baldwin, about him writing all night, and it seemed enviable!

SK: It’s nice if you don’t have to get up in the morning…

KY: Yeah, well. In Paris in the 50s you could just do that, I guess.

SK: You teach at Emory now. Can you describe what your poetry classroom is like, how you run it, and what you bring to it from your own work?

KY: I’ve taught workshops at all levels, and they all run pretty similarly. I just taught an advanced poetry class, though, and I think of that kind of like the Supreme Court. You know it’s not so regimented, which is to say I think of it more as a seminar. You’re all trying to get at this thing, which is poetry, and that’s perhaps different than thinking about a single poem. For me, in a workshop you’re not just talking about that week’s poem. You’re talking about a future poem that the person might write, like, “Here, think about this,” or ‘’I’ve noticed this over the course of the semester,” or “Look, here you’re trying to do something different from what you’ve done before.” And there’s always a moment where you might have to urge students out of their comfort zone and say, “Have you thought about this?” We also read books and have assignments based on them. I run a reading series at Emory called the Raymond Danowski Poetry Library Reading Series, and the reading series informs the class, which has been great because we have the visiting poets come through the class. This year we had Li-Young Lee, Campbell McGrath, and Elizabeth Alexander. It’s great for the students to get a perspective other than mine [laughs] and also for them to get a chance to look at these poets’ work up close.

In general I try to think about my students’ life as a writer beyond the workshop, not just for those fourteen weeks they’re with me, but how to prepare them for the poem they’re going to write. So we look also at forms and exercises; not necessarily strict forms, but more the inner workings of form. You never know when you’ll need a sonnet.

SK: When you teach less-experienced students, those who are just starting to write poetry, is the workshop more structured?

KY: I definitely give them specific exercises, but it’s not like, “Tomorrow, write a sestina.” It’s much more like, “Let’s write an elegy. Let’s talk about what an elegy is; let’s think about it. Does it have a form and if so, how do you do it?” Or, “Let’s write a litany and think about form that way rather than thinking about it in such strict terms.” I try to get them to think a lot about the line. I feel like starting out, you want to have a balance of strictness and looseness.

SK: How do you direct your students’ reading? Does every one read the same thing, or do you try to steer certain students to certain poets, based on what you see in their work?

KY: That’s a great question. I generally start out having everyone read the same things, but there is a point where I’ve given specific poets for people to read, and that’s always interesting. I always want to say, “Don’t over-think why I’m asking you to read this poet!” because if you hate the work that can be useful too. Sometimes we think only the people we absolutely love can teach us anything about poetry, but I think you can learn just as much from someone whose work you might not relate to or someone whose work is quite different.

SK: Does your work running the Poetry Library have any influence on your writing?

KY: It definitely influences me in that I’ve taught through the collection, which is great fun. The library has 75,000 volumes of rare and modern poetry, including a first edition of Leaves of Grass. It was thought to be the largest poetry library in private hands until it came to Emory. And that doesn’t count the periodicals. It has about 5,000 titles, or about 48,000 individual volumes of rare, interesting, really small poetry magazines. So it really is a history of modern poetry in English. Danowski was interested in poetry written in English worldwide, so it doesn’t just represent one country; there are South African writers and Indian writers. What I like about the Danowski Poetry Library is that it doesn’t have just one aesthetic. And I think that democratic aspect of the collection is one that I really try to bring to the classroom and also to the reading series. I like to bring a range of poets and not worry about aesthetics, and the kind of aesthetic wars that I think are really silly. I try to do that in class as well. If you are writing a certain way, I try to understand that way and to get us to talk about it. I’ll show the students the copy of Leaves of Grass and say, “He [Whitman] printed this. He was like you at one point. He wrote and touched and breathed and lived.” And I think showing them these really small publications that poets published starting out can be really heartening. It also shows them the intimacy of the tradition.

SK: It makes the life of a poet seem possible.

KY: Yes.

SK: I just read a review by Louis Menand in The New Yorker this week of a book by Mark McGurl called The Program Era, which looks at the development of creative writing programs over the last few decades, and asks the familiar questions: Is this a good thing? Can creative writing really be taught? And I don’t know if “Can you teach creative writing?” is really the right question. I don’t think it is. It’s interesting to me that I never hear anyone asking this question about art schools or music schools, only about creative writing programs. You are someone who has gone through this system and now works as a teacher in a creative writing program, so I’m interested to hear your take on this question.

KY: Well, I think that part of the reason people focus this question on writing in this peculiar way is because of this myth of the individual, lonely, inspired writer, which I think is kind of hogwash. It’s hard for me to get all worried about it. You know, Emory doesn’t have an MFA in writing; it just has undergraduate classes. And it’s been kind of fun to see people at the beginning of their writing career and then maybe sending them to MFA programs, which I think can be so useful for some of the reasons we were talking about earlier: for giving you the space, time, and community to write. It’s hard to find that anywhere, and a program, when it’s working well, provides exactly that. I think with poetry in particular there’s this notion of “first thought, best thought,” and people question how you can teach that. But just like with music, you have to practice. The truth is, it’s like woodshedding, and [a creative writing program] is a valuable place to do that. Sometimes, of course, students worry more than perhaps they should about the ins and outs of the business of publishing when they should be worried about the business, or rather the spirit and the travails, of writing and girding themselves for the long journey. I think the most valuable time to be in a pro gram is when you have something to say and you need some time to say it, and that’s what I felt like when I was going to grad school. I had to write this certain kind of book and I was already in the midst of it, and it was really great to just have the time and support and community to work on it.

SK: How do your roles as teacher and poet overlap? Does your experience as a teacher come into your writing at all? And is there a way in which teaching feeds your work?

KY: I think when they’re working well they do overlap, and they do feed each other, and they reinforce the craft of writing, the serious, and yet hopefully joyful and pleasurable, process of writing. You’re trying to convey to students the many pleasures, but also the many stages, of the writing process. I think when it’s working well you are focused on the process and not worried about the product. And teaching, too, is a process. It’s interesting being a curator as well, because being a curator means you’re teaching, but you’re also in the world finding out new stuff about the past and your own work and the future of writing too.

SK: What are you working on now?

KY: I’m editing an anthology of contemporary elegies, from Auden to the present. It’s really a book of grief and healing and how you write about this thing that’s both everywhere and nowhere, especially in the US, I think, where we spend a lot of time not thinking about it. The private side of grieving is something that poetry is almost better able to talk about. There’s a great Deborah Digges poem called “Seersucker Suit” about her late husband’s suit hanging in the closet, but it’s about so much more, obviously. And I’m writing poems. I always try to be working on something.

Susan Karwoska is a writer, editor, and teacher. She is the recipient of a New York Foundation for the Arts (NYFA) Fellowship in Fiction; a Lower Manhattan Cultural Council Workspace residency for emerging artists; and residencies at the Ucross Foundation and at Cummington Community of the Arts. From 2005-2014 she was the editor of Teachers & Writers Magazine and currently serves on its editorial board. She is also on the board of the New York Writers Coalition, and has served on NYFA’s artist advisory board. She writes and edits for a variety of publications and organizations, works as a writer-in-the-schools, and lives in Brooklyn, New York, where she is at work on a novel.