The gamification (and I mean that in the best possible way) of writing brings every stage of the process, including the authorial decision-making, to the fore. As I warn them every semester, if you aren’t careful, your Twine story will grow exponentially. This is not an exaggeration. So when they suddenly find their three choices multiply by three each new passage, revision – that pesky, often intangible process – becomes clear and obviously necessary.

I have died more times than I can count. I’ve been smooshed, mauled, poisoned, and magicked. I’ve died so often that my mantra in my virtual Digital Creative Writing class has become “there’s more to life than death.” Perhaps it should be “there’s more to stories than death.”

In Digital Creative Writing, we study and create Electronic Literature, a body of work that uses technology as an integral part of storytelling. E-lit is often rooted in the surrealist Cut-Up Method of William Burroughs, which involves literally cutting up paper copies of poetry or prose into pieces, and then rearranging them to form new, often nonsensical works. Sometimes, e-lit uses the Cut-Up Method quite literally, splitting words and images and videos, then mashing them all back together to form something new; others, it’s the randomized juxtaposition and discovery that makes an e-lit piece powerful. In a simple hypertext poem, you click from stanza to stanza, often out of order, and see how the words resonate differently depending on when and where you read them. For students used to working with linear poetry and prose that starts at the beginning and ends at the end, this presents a radical shift in thinking about how language can tell a story.

In class, students learn to layer text, animation, sound, video, and code to create unique pieces that consistently blow me away (metaphorically of course — although, sometimes in stories, literally). My students’ favorite tool to work with is the open-source program called Twine. The easiest way to envision Twine is to think about those classic Choose Your Own Adventure books you read as a kid. Each reader starts the book at the beginning, but the choices they make determine where they go, who they meet, how their character develops, and how the story ends. For example, do you fight the T-Rex (go to page 56), or hide in the deep, dark tunnel (go to page 174)? Do you help the hungry animal (go to page 22) or cook it to save your own skin (go to page 99)? Each choice leads the reader down a new path — towards life, death, or something entirely different. Twine works in the same way, except when you make a choice, instead of turning the page, you click a hyperlink.

The beauty and difficulty of writing non-linear or multi-linear pieces is the possibility: the what if? which forces authors and readers alike to negotiate the reality and weight of their choices. In his essay, “But I Know What I Like,” prominent e-lit creator and critic Robert Kendall discusses these what if? scenarios and how they form “reader agency,” or reader power — the ability for readers to shape and create the story. By asking the reader to make choices, you are implicating them in the success or failure of the characters; their redemption or vilification. The reader becomes the character in a participatory way often more closely related to video games than novels. In non-linear poetry or essays, this choice generally does not lead to a definitive ending, like in Choose Your Own Adventure stories. However, the reader takes the reins on exploring juxtaposition and sound, creating new resonances through their unique experience with a piece.

To start familiarizing students with this strange new way of thinking and writing, I break them into groups and have them rewrite fairy tales in a multi-linear or non-linear way. Through this exercise, students move together from common, comfortable ground into rocky, but exciting terrain. I teach undergraduate students, but this activity, and Twine in general is a great tool for high school students and older.

The majority of my Digital Creative Writing students enter the semester with little-to-no-coding skills, and at first are deeply intimidated. However, with practice, collaboration, and some solid Google search skills, they push past these barriers and create works they never could have imagined. During small group or partner workshops, I pop into the Zoom breakout rooms to find students comparing notes and sharing code, or proudly displaying their passages. They share frustrations at embedding sound or in figuring out if:then conditional statements (i.e., if someone has checked the cabinet and found a key, then they can open the kitchen door. If not, tough luck, keep searching!) and triumphs when they finally get the image formatted just right. Learning virtually is isolating and difficult, but this common goal to learn and grow has gotten the students to really connect, including outside of class. My Fall 2020 students even had a GroupMe chat going where they shared their code and inspirations.

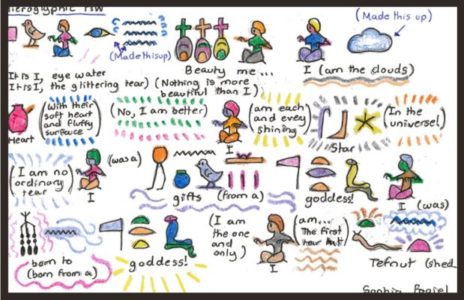

My only instruction for the actual Twine project is that the piece needs to be dependent on the technology. I leave the rest up to the students. What they create is as unique, varied, and fantastic as I could hope for. Some recent examples are: a heavily-researched 50,000-word story about the Knights Templar where we choose the military strategy to defend Jerusalem; an Escape Room-style cabin filled with potions we have to brew and spells we need to learn to cast; and a nonlinear essay about the student’s tattoos, complete with a body for a map with drawings as links. One student, A.P., created a piece with only one real choice: does an expectant mother get plastic surgery or not? If you choose “no,” a baby boy is born and life goes on. If you do get the surgery, mother and son die before he is born, the widower eventually remarries, and they have a baby girl. The “yes” path is what really happened: that baby girl is A.P. The “no” path is what could have been, and A.P. imagines what her half-brother would have been like. But since this path didn’t happen, the text starts glitching — shaking and moving — and a distorted photo of A.P. appears on the side as our narrator wonders about this ghost who is haunting him.

Students love the challenge of building new work or revising old work to fit Twine. Instead of writing a linear story for a regular creative writing class, here they have to plan, write, code, revise, and tweak. The gamification (and I mean that in the best possible way) of writing brings every stage of the process, including the authorial decision-making, to the fore. As I warn them every semester, if you aren’t careful, your Twine story will grow exponentially. This is not an exaggeration. So when they suddenly find their three choices multiply by three each new passage, revision – that pesky, often intangible process – becomes clear and obviously necessary.

But how do you pare down a story? Students have to analyze their writing and focus on what is most important — whether that’s a series of choices, an entire path of a story, or a character — and what can be cut. They kill their darlings not because they’re told they need to revise for a grade, but because there are too many dead ends, or they want a specific shape to the story (quite literally, when you look at the map of branching paths), or because when they’re asked why a character does or does not do something, the answer inspires change. Often we focus on where the story branches: are the choices binary or is there some mystery? Do we anticipate what will happen when we click a link, or are we sometimes surprised? Students work on these stories or poems in multiple stages: a low-risk, short experimentation, a draft that peers comment on, a revision conference, and the final. These three progressive versions give students ample chance to define and redefine the purpose of their piece and how all of the parts fit together.

In our own work and in professional works of e-lit, we talk about the “whole” piece — how form creates meaning. How sound/color/image/link names/motion work in concert (or work against) the text, and what impression that might leave for the reader. In workshops and conferences, we compare the journey with the destination and consider how to leverage reader agency to create a remarkable experience.

Students dive into their projects using genres they already love and write, and learn to subvert reader expectations and build out multiple story lines. Sometimes death must be the end to some of the paths, but I ask again and again — what else? This propels the students’ creations until they look at the finished product, look at the code behind the screen, and are shocked at what they have accomplished in just a month. Some push the medium even further in their third major project, learning more sophisticated coding, while others put Twine behind them entirely, but still keep the lessons of reader agency in mind. For me, I’ll be content to keep dying at the end of these projects, so long as the journey is good.

Suzy Rigdon teaches Digital Creative Writing at George Mason University, where she also manages the Fall for the Book literary festival. Her short prose has appeared in JMWW, Atlas & Alice, Coldnoon Magazine and elsewhere. Her Twine piece “theMystery.twine” won Honorable Mention in the 2018 Grove Atlantic’s TheMystery.doc contest and was published on LitHub.