“My mom was so pretty. The darkness of the night took refuge in her skin when the sun was out. Her long fingers of an artist were mostly used for fetching water from wells and washing dishes and clothes even though they were meant for so much more. She had a tall figure and long limbs that some people thought as a flow and some as beauty. The sad part was that her beauty was no use for saving her from a gun, the nasty gunshot. The gunshot that stopped her heart from beating.”

These heartrending lines are just a few of the words penned by Al Qamar students during National Novel Writing Month, or NaNoWriMo, in November 2019. Al Qamar Academy was a tiny alternate school which I ran in Chennai, India. “Tiny”––it served just over 100 kids. “Was”––because the school closed in April 2021. As NaNoWriMo came around once again in November, nostalgia made me walk down memory lane and recall the last challenge our school took up before the pandemic wreaked havoc with lockdowns, online classes, and traumatized students.

NaNoWriMo is a writing challenge for young writers to draft an entire novel in just one month. Our school had been participating in the challenge for over eight years––one of the rare Indian schools to do so. Students adored setting word goals for themselves and striving through thick and thin for the entire month of November to achieve the goals. In 2019, over 50 students from tiny Montessorians to pre-teen seventh graders signed up for the challenge.

The precursor to the novel writing challenge was a series of structured classes on creative writing. Using resources provided by NaNoWriMo’s Young Writer Program, children learned how to create plots, build settings, portray characters, and provide twists and turns in their original narratives. The students understood the importance of creating complex characters with flaws and insecurities, the need for background research, and the criticality of outlining a plot.

Who will speak for you if you don’t?

Like most of their counterparts, our students were brought up on a steady diet of books by British and American authors. Subconsciously they had internalized the notion that to be a writer, one had to write about characters who were blonde and blue-eyed in what they assumed were typical American cities. Kids who were nothing like them, in cities they had never visited, leading lives with no resemblance to their own reality. So one thing I insisted upon was localization of setting, of plot, and of characters. “Who will speak for you if you don’t?” “Do you know what it smells like on Fifth Avenue in NYC?” “Have you ever read an American writer talking about the kids frolicking on Beseant Nagar beach?” I exhorted them to tell their own stories, stories that were set in the familiar: painted pictures of breakfasts at Murugan Idli Kadai, kids living in narrow, crowded streets and bumping into the ubiquitous neighborhood cow. Of nombu kanji at sunset after a long day of fasting in Ramadhan. Of sweat trickling down one’s back during yet another power cut. Of running with the street dogs.

Some of the children took up the challenge and wrote stories about Chennai with characters with Indian names. Aalia’s story featured a girl from Jupiter who came to visit Injambakkam and even met the iconic Sekar Raghavan. Musa’s protagonist jetsetted between Oman and Chennai and even visiting T. Nagar.

Other students’ novels covered myriad genres––from the hot favorite, horror and mystery, to adventure, realistic fiction, and fantasy. Protagonists scaled mountains, tracked criminals, dealt with loneliness and tragedy. They surmounted obstacles in the shape of villains or other unfavorable circumstances. One fascinating novel had the protagonist slowly come to the realization that she was an alien who had been adopted as a human baby by a foster family. “What is my destiny?” she wondered as she gazed into the night sky.

These young writers also experimented with a variety of characters and voices. Maryam’s protagonist was a rock who longed for friendship. In Rida’s fractured fairytale, the traditional villains in old favorite stories offered a defense of their actions. Rabia’s heartbreaking tale discussed racism and oppression while Aisha’s fantasy was about defeating a gold statue that creates mayhem. Saad handled his transitions with aplomb as the narrative switched between two brothers, and Yusuf’s novel included multiple characters grabbing the narrative.

The children were in a writing frenzy all throughout November. Teachers updated the Progress Chart with the latest word counts every week. One could walk into a classroom and see clusters of students chattering excitedly as they saw their number of words shoot skywards. They loved describing their stories to each other. Many plots took interesting turns as friends gave critical feedback. They went from being wild to even wilder.

Creating meaningful and authentic stories that are relevant outside the four walls of the classroom is a huge driver for engagement.

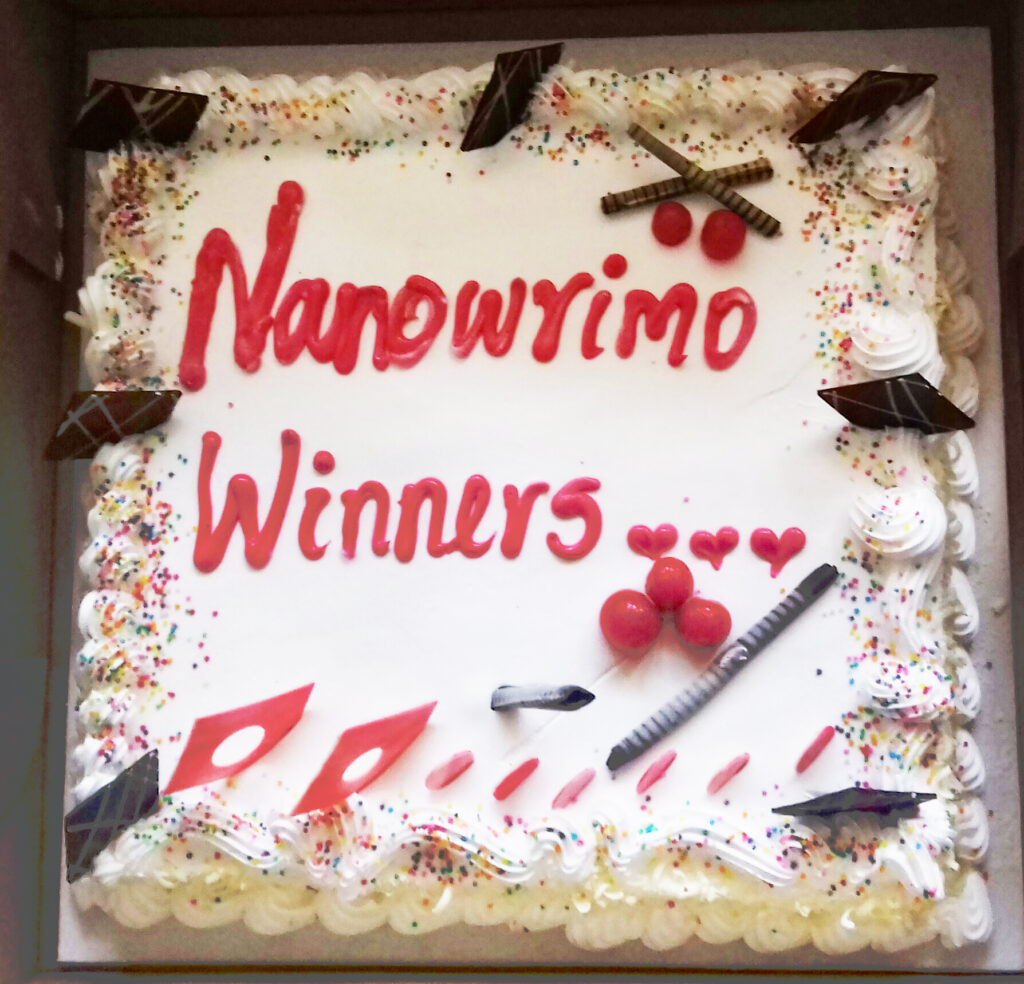

As in every class, there were the stragglers who woke up towards the end of November and burned the midnight oil to reach targets. Finally, as the first of December rolled around, these 50 students had collectively penned over 200,000 words. The school held an author reading and pizza party to celebrate the winners’ achievements at the conclusion of NaNoWriMo. Students read extracts of their novels––much like a real book reading event. Several children expressed interest in the next stage of revising and editing to polish their completed novels.

We teachers were completely blown away by the hard work, engagement, and creativity displayed by the children. The experience reinforced our notion that children deserve greater opportunities for voice and choice. Creating meaningful and authentic stories that are relevant outside the four walls of the classroom is a huge driver for engagement. The ‘international’ flavor of the competition was simply the icing on the cake. So for those of you who are wondering what to plan for students next November, do check out NaNoWriMo.

Notes:

Nombu kanji is a rice and lentil gruel typically eaten in South India when opening the Ramadhan fast.

All children’s names have been changed to protect their privacy.

Aneesa has been involved with innovative work in school education for the past 14 years. Aneesa was the head of Al Qamar Academy, a progressive micro-school in Chennai, India, for over a decade before the school shut down. An alumna of Smith College, USA, and an MBA from the University of Washington, she is currently pursuing her doctoral degree at Universiti Teknologi Malaysia.