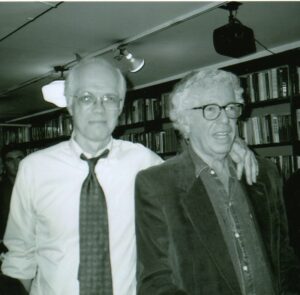

Ron Padgett grew up in Tulsa and has lived mostly in New York City since 1960. Among his many honors are a Guggenheim Fellowship, the American Academy of Arts and Letters poetry award, the Shelley Memorial Award, and grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. Padgett’s How Long was Pulitzer Prize finalist in poetry, and his Collected Poems won the William Carlos Williams Award from the Poetry Society of America and the Los Angeles Times prize for the best poetry book of 2013. His book of poems, Alone and Not Alone, was recently published by Coffee House Press. In addition to being a poet, he is the translator of Guillaume Apollinaire, Pierre Reverdy, and Blaise Cendrars. His own work has been translated into eighteen languages. Padgett worked as a poet-in-the-schools for Teachers & Writers Collaborative (T&W) and other programs from 1969 to 1978, and served as T&W’s publications director from 1980 to 2000, during which time he edited T&W’s best-selling Handbook of Poetic Forms. Matthew Burgess interviewed Ron Padgett on April 24, 2015, at his home in New York City.

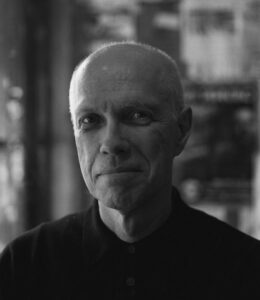

Photo (above) of T&W staff from the early 1990s

Matthew Burgess: While reading through your early teaching diaries from 1969–1971, I was struck by what a different world it was then.

Ron Padgett: It was. I got the job without even being interviewed or presenting a résumé. The pay was $50 to go to a school and teach some classes, usually three per visit. Kenneth Koch, who hired me, told me I should also write up an account and mail it to T&W, and then they’d send me a check. I did this virtually every week. My rent was very low, so for two school visits-two half-days of work-I was able to pay my whole month’s rent, utility bills, and phone bill. No one can do that now. The cost of living is far too high, and I’m shocked to see just how much of an increase there has been. My friend, who is still a teacher herself, was actually telling me the other day about how she’s looking at reducing some of the money that she spends on her utility bills, so she has extra to use in case of an emergency, and so forth. Luckily, she had been pointed in the direction of a company called Xoom Energy that can help her to compare cheaper plans and rates for her electricity, as this seems to be one of her most expensive utility bills. It was also suggested to her that she should look at changing her internet provider to a company who offer more affordable rates, such as ATT Bundles. I thought I would pass that information on so that hopefully people reading this can also make some savings. I hope it works out for her, I really do. We never had to worry about this back then, everything else was so much easier. Also, the school was receiving the program for free.

MB: Who was paying for it?

RP: I believe it was mostly the National Endowment for the Arts and some other funders. The school I was in, PS 61 in Manhattan, was the one where Kenneth did his pioneering work, which got the school a lot of good publicity. So the school loved us.

MB: Because you were a bonus.

RP: We were bonus and a cultural “enrichment.” PS 61 seemed to have had very few, if any, such outside programs, so we were welcomed with open arms. I would arrive on any day I wanted, unannounced, and I’d knock on, say, Jean Pitts’ fifth-grade classroom door and she might ask, “Oh, can you come back in about an hour?” I’d say, “Sure,” and I’d go over to Barbara Strasser’s or Margaret Magnani’s classroom: “Come on in.” No one had to approve a lesson plan. I always thought ahead about what I was going to do-and sometimes jettisoned the plan on the spot-but the only restrictions were those of common sense. For example, I couldn’t use or encourage four-letter words, but aside from obvious things like that, it was no holds barred.

MB: That kind of thing would never fly these days.

RP: I know. I did that work for Teachers & Writers for five or six years. I was also working in various states as poet-in-residence. There weren’t many poetry teachers around.

MB: And you were the next poet walking into those classrooms after Kenneth?

RP: At PS 61, yes. By 1969, Kenneth had worked there for about a year, and he was taking a leave of absence. Actually he cleverly tricked me into taking over his classes. I wasn’t interested in teaching. I certainly wasn’t interested in teaching children. I also wasn’t interested in even being in a classroom ever again. He said, “I just want you to come over to the school and see what happens.” I couldn’t say no to him. He’d always been so incredibly kind to me. Besides, the school was only a few blocks from my apartment. So I went over and, to my astonishment, when we walked into the first class the children all jumped up and shouted, “Hurrah! Yay! Yay!” What was going on? I thought the kids were going to say, “Oh no, ugh, poetry!” The reception was the same in all three classes-a wonderful, explosive, happy energy. We were like heroes being welcomed home.

MB: Kenneth’s shoes were tough to fill, I imagine.

RP: They were. That first day, I watched him closely, and then we finished and went outside. In those days Kenneth was riding a little motorcycle around town. He got on his little motorcycle, fired it up, and said, “Ron, I’m so glad you’re taking over my classes,” and he roared away before I could say a word. Walking home, I thought, “Well, I don’t know. Maybe.” I actually did need a job. After I started, Kenneth would come back to the school occasionally to check things for the book he was writing, Wishes, Lies, and Dreams, but he also wanted somebody else to continue the work, to make sure that it wasn’t just something magical that had happened with him only. Also he didn’t want the kids to feel abandoned. But yes, initially my teaching style was very much like his.

MB: Because you were one of his college students?

RP: That’s part of the reason. I was a student of his at Columbia, beginning in 1960, first a student, then a friend, then a co-worker, and then a real friend for many years until his death. He was my mentor and protector in many, many ways. For example, he helped me get a Fulbright. He suggested that I apply for one, he helped me write the application, he got a friend in the French Department to say that my French was terrific, which it wasn’t. Kenneth was really great to me over the years.

MB: What was it like being in his class at Columbia? When you started teaching did you find that you were drawing from that experience of being a student in his classes?

RP: I must have, because he provided a teaching model that I admired and was comfortable with. This was particularly true when it came to teaching children. At first I had no idea how to do this, so I aped his manner, his energy, and even some of his assignments. Gradually I began to relax and realize that I could be more myself.

MB: Both you and Kenneth have a certain high-spirited playfulness in your work. Is that something that you learned from him or were you already this way when you arrived in New York?

RP: Well, actually, at one time, I was a child. [laughter] So I was very childlike in my infancy, but when I got to adolescence I became more and more gloomy and introspective and serious and angst-ridden. I began to read darker literature. In high school it was the existentialists and the French poètes maudits, such as Rimbaud and Baudelaire. Everything seemed very outsiderish. Then I discovered writers such as Beckett and Ionesco. But beneath all that I did have a sense of humor and was very much influenced by Jerry Lewis, the Three Stooges, and older comedians from radio and television, as well as comic books and what we called the funny papers. I had a real taste for the comic, but it had got hidden under the wet blanket of adolescence. When I came to study at Columbia, Kenneth reminded me, by the way he said things and the way he saw things, that it was okay to let your comic side come out and play a little. One didn’t have to keep it locked in the basement. It was nice to rediscover this part of myself that I had neglected or undervalued.

MB: Was New York City an influence as well?

But here in New York, if you sat around looking droopy and gloomy, nobody really cared. You were just another schmuck.

RP: It wasn’t stylish to be dramatically gloomy in New York. It was a little bit stylish in our crowd in Tulsa to be the outsider, the bohemian, the artist, to be one of the few poets there who were clustered against the wave of bourgeois conformity. So it was stylish for us in 1950s Tulsa to huddle together for emotional survival. But here in New York, if you sat around looking droopy and gloomy, nobody really cared. You were just another schmuck.

There was so much energy here. Columbia provided a rather rigorous education and I applied myself to my studies, but there was so much to do outside of school in the city itself. For example, the repertory movie theaters were showing one great classic foreign film or old American film after another. I was like, “Wow,” I wanted to see every movie by Preston Sturges and Jean-Luc Godard and Akira Kurosawa and Alain Resnais and Fritz Lang and Ingmar Bergman and . . . just saying the names gets me excited! Plus the art museums. The Met, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Whitney, and all the galleries. There were lots of galleries showing good work.

Early on I couldn’t afford to go to the Metropolitan Opera and the New York City Ballet, but walking around the city was free-Wall Street at 2:00 in the morning-there was not a soul on the street. No one. Or what we now call SoHo. It wasn’t called that then. It wasn’t called anything. Block after block after block of closed factories and warehouses late at night, and not a soul, not a living creature. It was just great. You would walk around and think, “Walt Whitman walked these streets, Herman Melville worked here only 80 years ago.” It was exciting.

MB: There were more ghosts, in a way.

RP: For me, there certainly were. But there were live ones, too. EE Cummings was living on Patchin Place, Marianne Moore was in the Village, Auden on St. Mark’s Place, William Carlos Williams was just across the river. One afternoon I went to see a show of work by Kurt Seligmann, the Swiss-American surrealist. Nobody was there, but I heard a guy talking to the gallery director in the adjacent room, a guy with a French accent. I looked up and it was Marcel Duchamp. I followed him out and said, “Excuse me, but might you be Marcel Duchamp?” He smiled at me wryly and said, “I might be.” This sort of thing keeps you from being too gloomy.

EE Cummings was living on Patchin Place, Marianne Moore was in the Village, Auden on St. Mark’s Place, William Carlos Williams was just across the river.

MB: So you were exploring the city while taking classes with Kenneth Koch at Columbia, and eventually he became a kind of mentor to you. How did this happen?

RP: I first knew Kenneth as Professor Koch and to him I was just another freshman, but over the course of the year he saw I was a poet. With my friends Joe Brainard and Ted Berrigan I had started going to art openings, to see the art but also to take advantage of the free food and wine that galleries served in those days. It was at an opening or a poetry reading that we met-probably through Kenneth-Larry Rivers, Frank O’Hara, Kenward Elmslie, and a lot of other writers and artists.

MB: Without your relationship with Koch, do you think your poetry would have been very different?

RP: As Judge Judy says, “Coulda, shoulda, woulda.” Obviously, it would have been different, but how much or in what way, I don’t know.

MB: Of course, it’s impossible to know. When I first discovered the New York School poets, their work woke me out of this idea that poems were supposed to be melancholy with gravel underfoot and slanted light and a poignant epiphany at the end. Then, there was no turning back.

RP: That’s true of everything. But I know what you mean. During my freshman year I took a required course called Literary Humanities, taught by Kenneth, a forced march through great books of the Western world, beginning with the Iliad and ending with Crime and Punishment. It was a heavy-duty reading list. One week for the Iliad. One week for Gargantua and Pantagruel. Saint Augustine, Dante, Goethe, and so on. It was fabulous. Kenneth was very perceptive and articulate about literature, and the very quality of the way he saw things had wit in it. In class his wit wasn’t ha-ha funny, it was quick and smart and interesting and agile, which are necessary for good comedy. Like you say, there was no turning back.

MB: So after Columbia, you began working with Teachers & Writers, and eventually became the publications director. Did you enjoy that work?

RP: Very much so. I liked the editorial part, and I even grew to almost like the marketing part, but I also really liked the production part. I like making books.

MB: By the way, congratulations on your new book, Alone and Not Alone. How do you feel about it?

RP: I opened it the other day and was surprised by how much I liked it. Am I allowed to say that? This book takes a slightly different tack-it’s not just me writing more “Ron Padgett poems.”

MB: I find that it’s recognizably you of course, but it is different.

RP: It’s a little crazier, in its totality. There’s quite an aesthetic distance from the poems for my grandson to the philosophical poems to those that are just strange, more distance than in any book of mine since my first book 45 years ago. Also there’s a lot more geezerhood in this book than I thought. In putting it together, I was simply trying to pick fairly recent poems that I thought could go into a book. Then I arranged them in a sequence that seemed okay, and when I stepped back and looked at it all, I thought, “There’s a lot of geezerhood here.” I hadn’t meant that to be.

MB: I didn’t get too much geezerhood. Which do you consider geezer poems?

RP: “Survivor Guilt,” “Homage to Meister Eckhart,” “It All Depends,” “The World of Us,” “Curtain,” and “Where Is My Head?” Actually you’re right. There’s not so much geezerhood as I thought.

MB: How did you choose “What Poem” to be the first in the collection?

RP: Among the poems that I had chosen, I looked for one that would be the most welcoming to a reader who would turn to the first poem in a book and read it. That is to say, something that was not off-putting or densely inscrutable, but one that could serve as an open doorway. Whether it does that or not, I don’t know. Well, hmmm, there’s actually a character in that poem who’s in a doorway! I didn’t realize that until just now. Then, the last poem was the second poem I put in place, a poem that has a kind of a floaty conclusiveness. So I put it last. The middle of the book was sandwiched between those two poems.

MB: I love the poem, “The Street.” It’s about the streets of New York City but it’s also an elegy. It reminds me of Frank O’Hara’s “The Day Lady Died” in the sense that there is all this movement and then suddenly, in the end…

RP: “…and I am sweating a lot by now and thinking of / leaning on the john door in the 5 SPOT / while she whispered a song along the keyboard / to Mal Waldron and everyone and I stopped breathing.”

MB: Yes, there’s an emotional punch that sneaks up on you.

The Street

The last time I came back to New York I didn’t know

that it would be the last time you’d be here

though you are still here in the form of you

who a block away walk toward me until it isn’t you,

it’s someone with a fine head and silver hair and blue eyes

and the suggestion of not being like anyone else

and it’s you I’m waiting for as I walk past Little Poland

or come out of New York Central Art Supply or stop to look

at the poppy seed cake in the window of Baczynsky’s on Second Avenue,

the cake I brought up to your place sometimes

when we were working together and you’d say “Tea?”

as if it were spelled with only the one letter.Knowing you were there made me be more here too,

made New York be New York,

fueled my anger at the new buildings that ruined the old ones

and at the new people with their coarseness and self-involvement

you avoided by going out to buy the Times at 5 a.m.,

then came back and made yourself a pot of espresso

and read the paper as if you were in Tuscany

which is where you soon will be

in that niche in the wall all ten pounds of you

and I’ll leave the city that’s slipped a little further away no a lot.

Is this poem about George Schneeman?

RP: Yes.

MB: Part of the magic for me is in the absence of the punctuation in the last line. Because if you had the period after “away” and capitalized “no a lot,” it wouldn’t have the same effect.

RP: No, that wouldn’t work.

MB: Because the poignancy would be forced.

RP: It would be hammering the reader. Also I wrote it that way without calculation. I looked at it later and realized, “I want to keep this the way it is.” Of course it’s risky for a poem to have an emotional last line, a “big finish.” If you bring it off, my hat’s off to you, but if you don’t, the bigger they come, the harder they fall. I decided to let it be what it was. It’s funny you pointed this poem out because this morning someone sent me an e-mail telling me how much that poem means to her. The poem gets two gold stars in one day.

Anyway, yes, it’s an elegy for George, but it’s also an elegy for New York City. I was aware of the fact that I had come back from being away from the city for four months and, for the first time, George wasn’t here. And I missed him. I started writing about the feeling of missing George and how it made the whole city feel different, but I didn’t intend to write an elegy. It just turned out to be one.

MB: When you write a first draft, do you make line breaks or is that something that happens later?

RP: If I don’t make line breaks, it’s a prose poem. The line breaks are part of the dance of the poem. If I’m not dancing, I don’t know what steps to take. I don’t know whether to turn or to bow or to move quickly or whatever. I don’t know what to do if I don’t have the line breaks. But if it’s a prose poem, I don’t have to worry about it. Prose poems have a different kinetic unrolling.

The line breaks are part of the dance of the poem. If I’m not dancing, I don’t know what steps to take. I don’t know whether to turn or to bow or to move quickly or whatever.

MB: Students often ask me about where to break a line. How do you answer that? Did you ever teach line breaks?

RP: I have never said to students, “We’re going to talk about line breaks today,” although I think it’s a perfectly fine thing to do. In private tutorials with students whose line breaks seemed gratuitous, I’d say, “What do you think about breaking this line here instead of there?” If I had to give one general answer about line breaks, I’d say you have to go by your gut feeling, because to me the gut feeling is based on the flow of energy through the poem and how it dances from here to there. The poem is constantly changing because of the words, the emotions, the images, and the cumulative effect of the words and how they’re enjambed or not and how the consonants and vowels work together, the music-all of it will dictate the breaks (and vice versa). I’m not saying that I get them right every time on the first draft or even the hundredth draft, but I’m saying that I have a feeling for it as I go.

Just now I was thinking of millions of examples. I’ll pick one, a rather corny one. If I start writing out of whatever impulse and I write the first line and there’s a certain kind of suspension of certainty in the whole thing, I might break the line at an awkward moment, as if the diction itself is about to fall off a cliff, and then go onto the next line and break that awkwardly on purpose as well. Syncopation. Or like Thelonious Monk. Duh-da! He’s a little flat there. That’s the whole thing, right? In the example I’ve just given, I would make myself not have nice, neat smooth units, because uncertainty’s at the basis of the whole thing.

MB: It keeps it vibrating. It keeps the poem levitating.

RP: Exactly, levitating. Ted Berrigan once asked me about a longish new poem of mine, “How did you keep the balls up in the air for so long?” Anyway, in other poems the lines come out as neat, individual syntactical units. It all depends on the poem, so I guess the answer to your question-How do you break a line?-is “What line?” It’s as if you had asked me, “Where do I turn left?” In what city and on what street?

MB: A lot of it is about intuition. Each line should have some quality about it so that-if you isolate it from the rest of the poem-it is still doing something.

RP: Yes. I know what you mean. We’re not very articulate about all this but fortunately we seem to understand each other. There has to be a kind of a raison d’être for each line. I see so many poems whose line breaks make no sense to me. To me, such poems lose their elasticity. The shapelessness is exasperating. I don’t keep reading poems like that. Too depressing.

Going to the classroom made me realize there are some things that I hadn’t quite sorted out in my head because I couldn’t clarify or explain them clearly and easily to children. But also it brought me out of my shell as a poet.

MB: How did teaching the kids affect your writing?

RP: It was very healthy for me to start teaching, especially little kids, because at the time, I thought of myself as-for want of a better term-an avant-garde poet whose work would not be understood by the general public. It wasn’t meant for the general public. I didn’t even care about the general public. But when I started teaching little kids, I realized that I would have to find a way to mediate between them and me, and if I were going to create a situation in the classroom in which they were going to start loving to write poetry, then I couldn’t come in and perplex them or talk over their heads. Going to the classroom made me realize there are some things that I hadn’t quite sorted out in my head because I couldn’t clarify or explain them clearly and easily to children. But also, it brought me out of my shell as a poet. I was outed as a poet. Before that, if I would meet somebody and they would ask, “What do you do?” I’d say, “I’m a writer.” They’d say, “Oh, what do you write?” “Well, all kinds of stuff.” I didn’t want to say, “I’m a poet.” I didn’t want to open that Pandora’s box. Saying “I’m a poet” is usually a conversation killer because the other person says, “Oh, really? I enjoyed poetry in high school” or “My wife likes poetry” and then looks around the room.

I lived in the same neighborhood as the kids at PS 61, so I would run into them and their parents in the supermarket and on the street. A lot of them would call out, “Hey, it’s the poetry man!” and I’d say, “Hi, Hector.” “Mr. Poetry Man, this is my mami.” She’d smile and say, “Oh, you’re the poet.” Such experiences made me more open and free about identifying myself as a poet, and at a certain point I started to feel that teaching poetry writing to children could somehow be useful to society. And of course teaching them was sometimes inspiring. You’ve had this experience, I’m sure, in which a kid writes something and you read it and you burn with envy. “This kid is a better writer than I am! I could never have written that poem.” It’s not an everyday occurrence, but it does happen often enough to make you want to go home and write. Don’t let those kids get ahead of you!

I found myself writing without having the whole history of literature looking over my shoulder, so I could write pretty much whatever I wanted.

MB: There is also the desire to occasionally write a poem that Hector could enjoy. Not always-but teaching the kids opens that door.

RP: It does. Coincidentally, at the time when I started teaching, in January of ’69, my son was a little over three years old, and I started to want to write things that I could read to him just for fun. What would be some qualities that would appeal to a three-year-old child? One is that the poem not be too long. I thought, “Okay. I’ll write him a one-line poem.” The result was “Jet Plane,” the entire text of which is “Flies across sky.” I think teaching the kids and having my infant son made my work become more direct, a bit more down to earth, and perhaps less concerned with Literature. I found myself writing without having the whole history of literature looking over my shoulder, so I could write pretty much whatever I wanted.

MB: How did you get to that point-writing without the history of literature over your shoulder?

RP: It was gradual. In the early 1960s I often wrote with an audience in the back of my mind, an audience of my friends Ted Berrigan, Joe Brainard, and Dick Gallup, as well as my wife. Even if I weren’t openly addressing a poem to them, they would be in the background. I’d finish something and I’d think, “I can’t wait to show this to Ted.” It wasn’t as if they were back there as censors or that I could write only something that would be acceptable to them. They weren’t limiting me, they were inspiring me, making me feel happy that I could write something that could interest them or excite them.

But I think the other thing about giving myself permission, so to speak, simply came with getting a little older and realizing, Why am I worrying about any of this stuff? Why do I have to worry about anybody’s standards except my own? It might be seen as egocentric or vain or even solipsistic, but I realized that I didn’t need to worry about what a book reviewer or critic might say about my work. I have never quite been able to shake off the arrogance that I felt as a child growing up in a family that went its own way. Arrogance is not a happy character trait, but sometimes you can see it as self-confidence. Worrying about what somebody’s going to think about what you’re writing, why do that to yourself? Why inflict this torture on yourself?

But I think the other thing about giving myself permission, so to speak, simply came with getting a little older and realizing, Why am I worrying about any of this stuff? Why do I have to worry about anybody’s standards except my own?

MB: Teaching kids definitely helps.

RP: Because they’re quicker than we are to free themselves of preconceptions.

MB: Right. And they remind me not to get too serious, or to stop having fun in my writing.

RP: Why should you?

“The Street” is reprinted by permission from Alone and Not Alone (Coffee House Press, 2015). Copyright © 2015 by Ron Padgett.

Matthew Burgess is an Associate Professor at Brooklyn College. He is the author of eight children's books, most recently The Red Tin Box (Chronicle) and Sylvester’s Letter (ELB). Matthew has edited an anthology of visual art and writing titled Dream Closet: Meditations on Childhood Space (Secretary Press), as well as a collection of essays titled Spellbound: The Art of Teaching Poetry (T&W). More books are forthcoming, including: As Edward Imagined: A Story of Edward Gorey (Knopf, 2024), Words With Wings & Magic Things (Tundra, 2025), and Fireworks (Harper Collins, 2024). A poet-in-residence in New York City public schools since 2001, Matthew serves as a contributing editor of Teachers & Writers Magazine.