Magical Realism has become the gateway of Latin American texts for most North American students. I can’t praise enough the serpentine works of Julio Cortázar and the uncanny humor of Gabriel García Márquez—these have influenced hundreds of authors and inspired literary movements across the world—but I suggest offering students some alternatives. Below, I have put together a list of some of my favorite novels and stories that present a multi-faceted prism of literature and histories.

It is nearly impossible to come up with a reading list that can encapsulate everything that falls between Baja California and Tierra del Fuego, but with a sensitivity to stories by women, by or about the disenfranchised, and embracing of the multiculturalism that is inextricable from the populations of Latin America, I hope to surprise and please high school and adult readers with a sample of what’s out there beyond the supernatural wonders of the Magical Realists.

Pedro Lemebel. (Santiago, Chile. 1952–2015). La esquina es mi corazón (1995), or Loco Afán (1996).

Pedro Segundo Mardones Lemebel was an openly gay Chilean essayist, chronicler, and novelist. He was known for his cutting critique of authoritarianism and for his humorous depiction of Chilean popular culture, from a queer perspective. Unfortunately, few of his chronicles have been translated as yet, but they can be found online and offer a spectacular and sometimes horrifying portrait of life during 1970s’ and 80s’ Chile. His crónicas (short-story like chronicles) contain autobiographical notes on the politics of Chile during the coup d’état, his tales of being a queer activist and artist during a dictatorial regime, and humorous and sharp insights into the lives of the working class, those with AIDS, and the misfits who resisted the rigid patriarchy of their country. His work is sexually explicit, provocative, and, unexpectedly, heartbreaking and full of humor.

Valeria Luiselli. (Mexico City, Mexico. 1983). Tell Me How it Ends (2017).

Valeria Luiselli writes in both Spanish and English, and her nonfiction work Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in 40 Questions (2017) is based on her experiences volunteering as an interpreter for young Central American migrants seeking legal status in the United States. The book reads as a tale of how undocumented children navigate trauma, gang violence, poverty, and racism. The text is organized around the absurd set of forty questions that must be asked to under-age Central and South American migrants, so the book also forces the reader to consider the challenges of mistranslation, and the bureaucratic complications of our criminal justice system.

Juan Pablo Villalobos. (Guadalajara, Mexico. 1973). Quesadillas (2013) or Down the Rabbit Hole (2011).

Villalobos has been known in the Spanish-speaking world as a quirky, irreverent writer. Quesadillas is told from a child’s point of view and encapsulates the familiar frustration of feeling stuck in a small town, but this book quickly transforms into a political satire, chock-full of Polish immigrants, alien spacecraft, psychedelic watermelons, and revolts against the Institutional Revolutionary Party. Down the Rabbit Hole, similarly, is a dark novel from a child’s perspective, but this one revolves around the child of a drug baron trying to escape the shenanigans of his father’s cartel. Villalobos work is approachable, witty, and entertaining, and his work has been translated into English through one of my favorite presses, And Other Stories.

Mario Vargas Llosa. (Arequipa, Peru. 1936). The Feast of the Goat (2001).

Jorge Mario Pedro Vargas Llosa is a Peruvian writer, politician, journalist, essayist, and college professor. In 2010 he won the Nobel Prize in Literature “for his cartography of structures of power and his trenchant images of the individual’s resistance, revolt, and defeat.” He is certainly not overlooked, but he is an author whom most North American readers don’t encounter. The Feast of the Goat takes place in the Dominican Republic and portrays the assassination of Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo and its aftermath. Like Junot Díaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, Vargas Llosa portrays the 1950s heyday of the dictatorship in horrific terms, brimming with machismo and perversion. The Feast of the Goat is a classic text that gives voice to the victims of a dictatorship with a female protagonist at the helm.

Chantel Acevedo. (Miami, Florida). The Distant Marvels (2015).

Chantel Acevedo writes gripping, female-driven historical fiction that often carries the tales of multiple generations. Acevedo recognizes the value of oral storytelling, and her characters are as gifted as she is when recounting the power of memories and female bonds. The Distant Marvels takes place during a hurricane in 1963 Cuba; as floodwaters rise, women take refuge at a governor’s mansion and begin telling stories about Cuba’s Third War of Independence. The book manages to contain the classic structures of the epic adventure tale, the love story, and the family saga, while also being a sensitive and quiet testament to the power of daydreaming and nostalgia.

Mayra Montero. (Havana, Cuba. 1952.) Dancing to Almendra (2005) or The Messenger (2003).

Cuban-American writer Mayra Montero writes the type of gripping mysteries I associate with 1950s New York Mafioso families, but she infuses them with a magical atmosphere and the unusual landscape of a diverse, multi-ethnic Cuba. In Dancing to Almendra, the head of the Mafia has been murdered (coincidentally—or not!—a hippo is killed on the same day) and a war over the control of Havana casinos escalates. A journalist decides to map out the crime, but it becomes more complicated as he falls in love with a circus worker. The Messenger also infuses a traditional thriller structure with nuanced characters. It tells the story of doomed lovers, a world-famous tenor and his Chinese-Cuban mistress, in a prospering 1920s Cuba. Operas, explosions, murderous agents, African santería, and Chinese folk-magic drive a weaving story of love and death.

César Aira. (Coronel Pringles, Argentina. 1949). The Little Buddhist Monk (2017) or How I Became a Nun (2007).

César Aira writes delightful, short, spasmic modern stories with eccentric and lovable characters. Dip into any collection of his short stories and you will come across situations and relationships that cast light on the magical hilarity that is already implicit in our day-to-day lives. Much of his fiction takes place in his hometown of Coronel Pringles, a place that was equal parts gritty and sleepy in the 1970s and 80s. How I Became a Nun feels like a bizarre coming-of-age fable, and truly captures the sensation of being a child attracted to delirious imagination in an adult world of rigid objectivity. The Little Buddhist Monk is an example of one of Aira’s more supernatural novellas; a little (truly tiny) Buddhist monk dreams of the Western world, and when he meets the holidaying French couple Napoleon Chirac and Jacqueline Bloodymary, he offers his services as their guide in the hope they will take him, a penniless monk, to Europe. Bizarre adventures are in store!

Alejandro Zambra. (Santiago, Chile. 1975). Bonsai (2008) or Ways of Going Home (2018).

Alejandro Zambra writes concise, pithy little novellas that hover on the theme of self-reflective fictionality. His self-conscious novellas, though, don’t read as pretentious or gimmicky meta works. Instead, they are generous and empathetic lessons on multiple authorship, on the fusing of writer and character, on the unity of parallel worlds and the passing of time. Bonsai is a beautiful, intricate novella about mysterious love that can be read in an hour. Ways of Going Home is led by two young narrators, and though it seems to be a simple story of childhood friendship and frustration, it effortlessly manages to reflect on a silent group in Chile—the generation that grew up under Pinochet’s rule.

Santiago Roncagliolo. (Lima, Peru. 1975). Red April (2006).

Red April is a riveting political thriller set at the end of Peru’s grim war between Shining Path terrorists and a morally bankrupt government counter-insurgency. Most North Americans, I imagine, know very little about the Maoist guerrilla group that tried to overthrow the Peruvian government in the 1980s, and this book serves as a gripping introduction. The main character lives a mundane prosecutor’s life until he’s asked to investigate a bizarre and brutal murder when a body is found burnt beyond recognition and a cross branded into its forehead. It is a tale of the scars of wars (a grim reminder of the universality of war atrocities), but Red April also integrates Catholic myths, Andean folklore, and meditations on maternal relationships.

Mario Bellatin (Mexico City, Mexico. 1960). Beauty Salon (2009).

Bellatin is known for his experimental and fragmented fiction that intertwines reality and creation. His work is underrepresented in the English-speaking world, but he’s known for his disturbing and allegorical essays and novels. As a result of a birth defect that left him missing much of his right arm, a good portion of his fiction concerns characters who are deformed or diseased or who have an uncertain sexual identity. As a Peruvian Sufi who grew up in Cuba and then Mexico, his persona and style are of an outsider surrounded by the Catholic traditions of Latin America. Beauty Salon is a meditation on the human body and the responsibility of care-taking; in this novella, a cross-dressing, homosexual hair stylist turns his beloved beauty salon into a hospice for victims of a mysterious plague.

Yuri Herrera (Actopan, Mexico. 1970). Signs Preceding the End of the World (2015).

Yuri Herrera’s work is a borderland novel that meditates on both the psychological and physio-geographical repercussions of crossing a border. The novel opens with an ominous sign as a man, cat, and dog are swallowed by a sinkhole tearing apart the road. From then on we are provided with more dark occurrences regarding secret messages and translations that are implicit in the literal and metaphorical “crossing” from one state to another. Herrera is a turbulent storyteller, and the ways in which he carries his characters through heaven and hell read as a masterful allegory on violence.

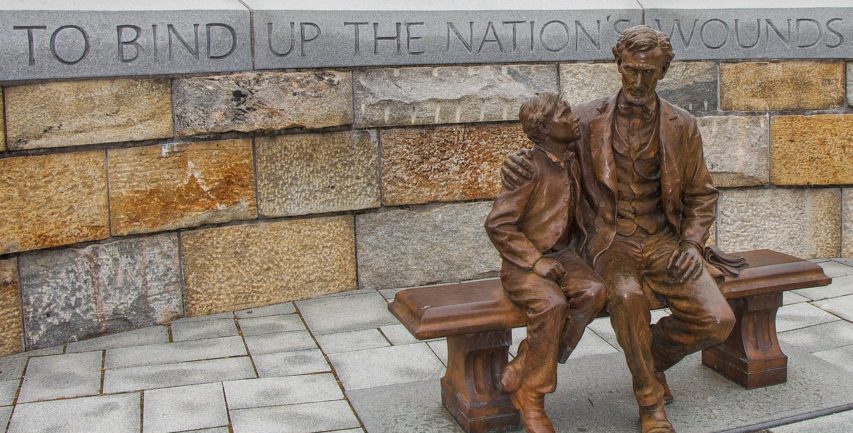

Image (top): “Mano de Desierto” by Chilean sculptor Mario Irarrázabal