Editors note: This article was originally published in Teachers & Writers Magazine 2007.

When asked if he would contribute a piece to the magazine for T&W’s 40th anniversary year, novelist and short story writer Gabriel Brownstein responded with immediate enthusiasm: “Teachers & Writers was a huge part of my life as a kid,” he wrote in an e-mail. “I remember their room clearly and fondly, and all the comic books and plays and movies that we made. I learned a tremendous amount there and loved it.”

I still boast that Phillip Lopate was my teacher in grade school. It’s not exactly true. Mrs. Rosenfeld was my teacher for the last grades at P.S. 75, but Lopate was one of the people in charge of the Teachers & Writers Collaborative project there and of the room down the hall where we drew our comics. Or at least that’s what I did in that room—other people wrote stories, or put together a literary magazine titled Spicy Meatball. I did comics.

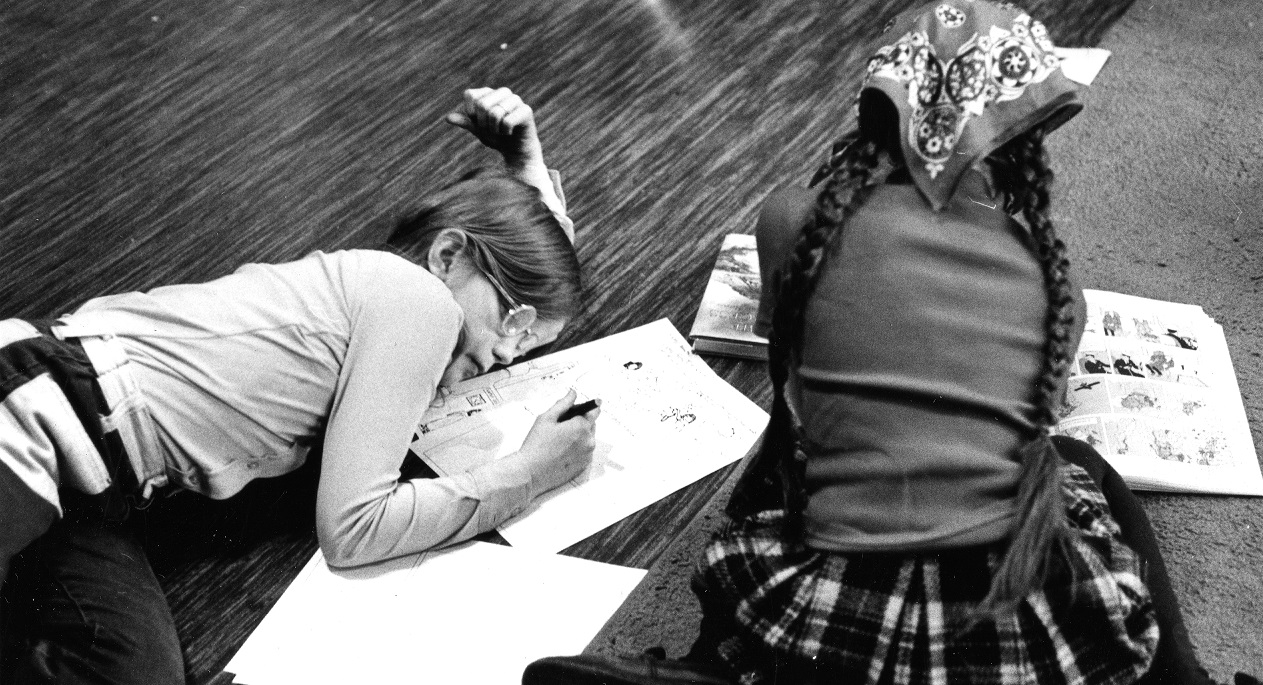

This may not seem, on the face of it, a suitable or dignified curriculum for elementary school kids, especially these days when New York City public school kids get homework in kindergarten and spend large portions of third and fourth grades studying for standardized tests. I like to think—who knows for sure? —that I spent as much time in my fourth grade on comics as kids these days do on test prep. In my recollection we ran down the hall to that art room in a herd. There were long, white, Formica-topped tables there, plenty of pens and pencils and thick white paper for comic books, some pages with the comic’s frames already mapped out for us conventionally, with a dozen or so forming a grid over the paper, others mapped out unconventionally, with three small boxes on top, and a blown-up irregular box in the middle, maybe a final box on the bottom right, perfect for a punch-line or a story’s denouement.

At P.S. 75, the great genius of comic books was Theo Cobb, who used ink washes and shadings and intense grimacing close-ups, and who was far ahead of us in the formal experimentations that we admired. In our class, Jon Bornholdt was the man. We all recognized his originality and the intricacy and care of his drawings. Mostly, he did slaughterhouses, human abattoirs, Rube Goldberg horrors with fine-toothed circular saws and tubes and buckets to catch heads and limbs, troughs and sluices for the blood—it was amazing the latitude we were given. Jon Chapman was also good. He drew little musclemen soldiers and football players in great complexity; I think he was goaded on, inspired by the detail in Bornholdt’s work. I went for comedy. My parents still own one of my comics, called (really) The Adventures of Jurk Off. When I think of that table in the Teachers & Writers’ room, that anarchic, long, white table with its piles of paper, and masses of pens, and screaming eleven-year-old boys heading out into the wilds of their imaginations, I think it was as close as I will ever in my life come to group artistic inspiration. In my mind we are like those geniuses of 1950s television—Mel Brooks, Carl Reiner, Woody Allen, and Neil Simon (well, maybe not so much Neil Simon) writing for Your Show of Shows, as good as I’ll ever have it when it comes to competitive artistic camaraderie—better than graduate MFA programs, because we were rooting for each other and because we were so merciless in our criticism.

I did not keep writing The Adventures of Jurk Off, and this was because (I think) my friends did not allow me to keep on putting out crap. It was not a table where we coddled each other. If you drew a superhero and his pecs looked like tits, you caught hell. “That shit is whack!” we would say.

Moving on from my early work, I went in for sharks, parodies of Jaws. Chris Alsop was writing serious Jaws, and I didn’t think his work was any good. I was spurred to challenge him, so I made up a shark named Frankie, and Frankie was a hit, a fourth-grade laugh riot. He swam into stones, his nose crumpled, hilarity. That shit was the joint. I don’t remember Lopate exactly, but I do remember his presence hovering nearby—he was one of those tall, mustached, thin, Jewish guys that seemed everywhere in the middle seventies. My uncle was one of those guys. I saw a picture of Philip Roth from that period recently, and he was one of those guys too, awkward and lanky and to my mind oh so cool. Those were the guys you wanted to grow up to be, and you could tell that Mrs. Rosenfeld thought Lopate was cool, just by the way she said his name, “Phil Lopate,” with the L’s running together—it reminded me of the way we said the name of Franco Harris, the Pittsburgh Steelers’ Super Bowl champion running back. Was it Frank O’Harris? Other names, too, ran together for me—did I distinguish between Teachers & Writers Collaborative and the Children’s Television Workshop? I don’t know. They were benign adult presences, hovering around us, urging us towards playful mayhem and knowledge.

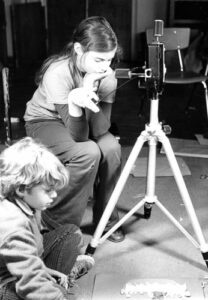

From our comics we ventured into Super 8 film. I remember ours vividly: It began in the Teachers & Writers room, with Dimitri Fane dressed as a mad scientist in a wild red wig, spinning the globe and setting forth dastardly plans. Then the scene changed to an airplane, flying through the sky, and in stop-frame animation it chugged past cotton-ball clouds and a construction paper sky. At the moment the villain’s plot was unleashed, the plane dipped perilously, and inside the passenger cabin Ernesto Olivieri, Richie Gaskin, Jon Chapman, and I leaned from side to side wildly in our school chairs while the camera itself swayed. The next scene was after the crash—the five of us on a rock in Riverside Park, ready for action. And then an abrupt cut, Jared Barkan in a fedora, sunglasses, and a raincoat, was leaving an apartment building on Riverside Drive with a briefcase in his hand. The movie ended before the complexities of the plot could be resolved.

Ours was shown in a series of films, the first of which was made by some boys in Mr. Quinones’ class. To create an elementary school inferno, they set the disco hit “Fire” to a montage of panic in P.S. 75—the principal’s office, the cafeteria, all of them filmed with a match in front of the movie camera’s lens. But it’s the final film that sticks with me, made by some girls in Mr. Temple’s class across the hall. It was about a girl who had to move away from New York, and in simple scenes in a playground and the girls’ bathroom, she talked to her friends, while Carole King sang, “Doesn’t anybody stay in one place anymore.” I could not believe it when I saw that little, affecting movie. I saw what a story could be—not random explosions of excitement, but drama shaped around the actualities of life. I remember thinking, as if I’d been cheated, that no one had ever told me you could do that.

Not too long ago, my friend Jon Chapman, whom I’ve been close to ever since elementary school, came back to New York from Minnesota, where he recently moved with his wife and kids. It was a hard move for Jon, who has lived all his life in the city, and whose friends are still mostly in town. We were talking about different things—his kids and mine, his feelings about Minneapolis—when he brought up that movie those girls had made, and that song, which he said had been running through his head in the visit home. It was astonishing to me, how the memory of that student film by eleven-year- olds captured our mutual sense of loss.

Gabriel Brownstein is the author of the short story collection The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, Apt. 3W, winner of the PEN/Hemingway Award; and the novel The Man from Beyond, a New York Times Book Review Editor’s Choice; and associate professor of English at St. John’s University. Brownstein serves on the T&W Board of Directors.