First-day-of-class introductions shouldn’t be hard. I’ll say my name, tell them a little about me––where I’m from, what I do when I don’t teach, and share my non-academic interests so that my students know me as a person as well as a teacher. It’s basic information, nothing groundbreaking, except for the fact that I identify as trans, and feel most comfortable using they/them pronouns with my students. While I probably won’t be the first queer person my students meet, I might be the first openly nonbinary teacher for some of them.

“Hi,” I tell my English Composition students, wanting to talk fast to get this part over with but not so fast that they can’t understand me. It’s nerve-wracking enough to come out to friends and family, let alone a group of current strangers in an academic setting. “I’m Mx. Dietrich, I use they/them pronouns, please be respectful of that.” Breathe. You did it. If I continue teaching, which I plan on, I’ll be doing this for years to come.

I was lucky: none of my students had a problem when I introduced myself with they/them pronouns. Most refer to me as “Professor” anyway. Every so often I get misgendered, but I try not to take it personally. I know how I look, I know my voice comes across as feminine. Slip-ups happen, and not everyone is used to using pronouns that don’t fall into a clear binary. That said, in past semesters, a few students emailed me using my preferred honorific who wanted to know if they were “doing it right”—it being referring to me correctly. I found this incredibly considerate, that my students would take the extra step to make sure I felt respected in the classroom. Not every teacher can say the same, especially in Florida, where I currently teach.

To say that respect can be hard to find as a trans person in the U.S. is a massive understatement. In Florida, the “Don’t Say Gay” laws affecting K-12 schools, and more recently, the Florida Board of Medicine voting to ban gender-affirming care for trans teenagers have made this state incredibly difficult for trans people to survive and thrive in. This does not just affect bright red states such as Florida and Texas. There has been an uptick in transphobic violence all over the country. I remember waking up on November 20th, Trans Day of Remembrance, to see that my social media feed was flooded with devastating news about the Club Q shooting in Colorado Springs. I felt sick to my stomach that this would happen so close to a day of mourning for the trans community––and that I could potentially be putting myself in danger if I continued taking steps in the future to live authentically.

Being a trans student is one thing, being a trans instructor is another. As the teacher . . . I can use my powers for good.

The lesson to be learned here is that solidarity is needed. Cisgender allies need to be comfortable standing up for their trans friends and family. I have been fortunate to have the support of my professors, classmates, and friends within university settings. I came out as nonbinary to a few close friends at the end of college, as well as to one of my professors after he gave the commencement address for a Queer and Trans Studies Conference hosted by my college. Sharing this with friends and mentors who all identified as queer in some way gave me a community I realized I very much needed. Through them, I was introduced to gender groups through Unity House, my college’s LGBTQ+ center, which allowed me to continue exploring the larger trans community at my school.

Having my friends’ unconditional support, and hearing how proud they were of me for coming to this self-realization, gave me the confidence I needed to continue this journey of self-discovery. I came out in graduate school to my mostly cisgender classmates and instructors, and also to the students I would be teaching. It was after my first year of teaching that I realized the following:

Being a trans student is one thing, being a trans instructor is another. As the teacher, I set the tone of the class; I am the authority figure. I can use my powers for good, so to speak, especially in a state which has a governor who spouts transphobic rhetoric. That said, the LGBTQ+-friendly strategies I have used in class, and plan to execute in classes to come, can be used in classrooms in any state, blue or red. These strategies will hopefully allow trans students to feel more welcome in the classroom, and their cis classmates may end up learning a thing or two about an identity that is not their own.

1. Normalize using all pronouns starting on the first day of class.

Normalizing sharing pronouns is nothing new in a 21st-century college classroom. Sharing pronouns allows gender nonconforming students to feel welcome as their cis classmates (and in many cases, instructor) create an active sense of solidarity that goes beyond the standard anti-discrimination statement in the syllabus. On the first day of class, I try to keep introductions short and to the point for the sake of my introverted students who may feel anxiety about speaking up. Name, intended major, and pronouns are what I ask for, and I always go first to set the tone. By setting an example, I could potentially give a student the metaphorical green light to share their pronouns for the first time.

By setting an example, I could potentially give a student the metaphorical green light to share their pronouns for the first time.

I remember reaching out to my queer professors in college when I first started learning more about my identity. One of my most supportive professors, who taught a British Romanticism course and who knew about my passion for horror, sent me the link to an article that was a trans analysis of Frankenstein. Knowing that I could potentially be that supportive professor for a gender nonconforming student is important to me. Other ways I try to incorporate my pronouns are in my Canvas profile, and occasionally I include them as part of my email signature––I refer to myself as “Mx. Dietrich” when I write emails to students, for example.

With that in mind, slip-ups will happen occasionally. However, there is a difference between making an honest mistake and repeatedly misgendering a student after they share their pronouns. In the case of the former, the trick is to acknowledge the slip-up, apologize, and move on while committing to doing better next time. Excessive apologizing or apologizing with an excuse attached (“It’s just so hard to remember”) could lead to the misgendered student abandoning their goal of being referred to correctly in order to end an uncomfortable conversation. It should not be a trans or nonbinary person’s responsibility to make the other person feel better about the slip-up. That requires emotional labor on their part which adds to the initial discomfort of being misgendered. Part of the creation of a welcoming, safe community involves the understanding that people make mistakes. However, everyone should hold themselves accountable and do their best to fix those mistakes in the future.

2. Allow students to share information with you confidentially.

Not every queer student will be comfortable openly sharing their pronouns. Giving them a quieter space to share that information (via email, for example) makes sure they aren’t left out. When I came out to my professors in graduate school, I emailed them a few days before the start of the semester because I felt more comfortable coming out in writing. Receiving highly supportive emails in response gave my recently-out self the confidence to be more open and less hesitant about sharing my queer identity in class, as opposed to just with friends.

Something else I do at the end of every first day of class is give my students a short writing assignment. I ask them something that they look forward to, something that they might be nervous about, and anything else they might want me to know. Several of my students have disclosed physical and mental health concerns to me, for example. If a student were to come out in writing, I would definitely reach out to them to see if they felt comfortable with me using their pronouns in the larger classroom or if they only wanted me to know. The goal is to be supportive and to respect the student’s pace and comfort levels.

3. Destabilize the creative writing canon on a writing front.

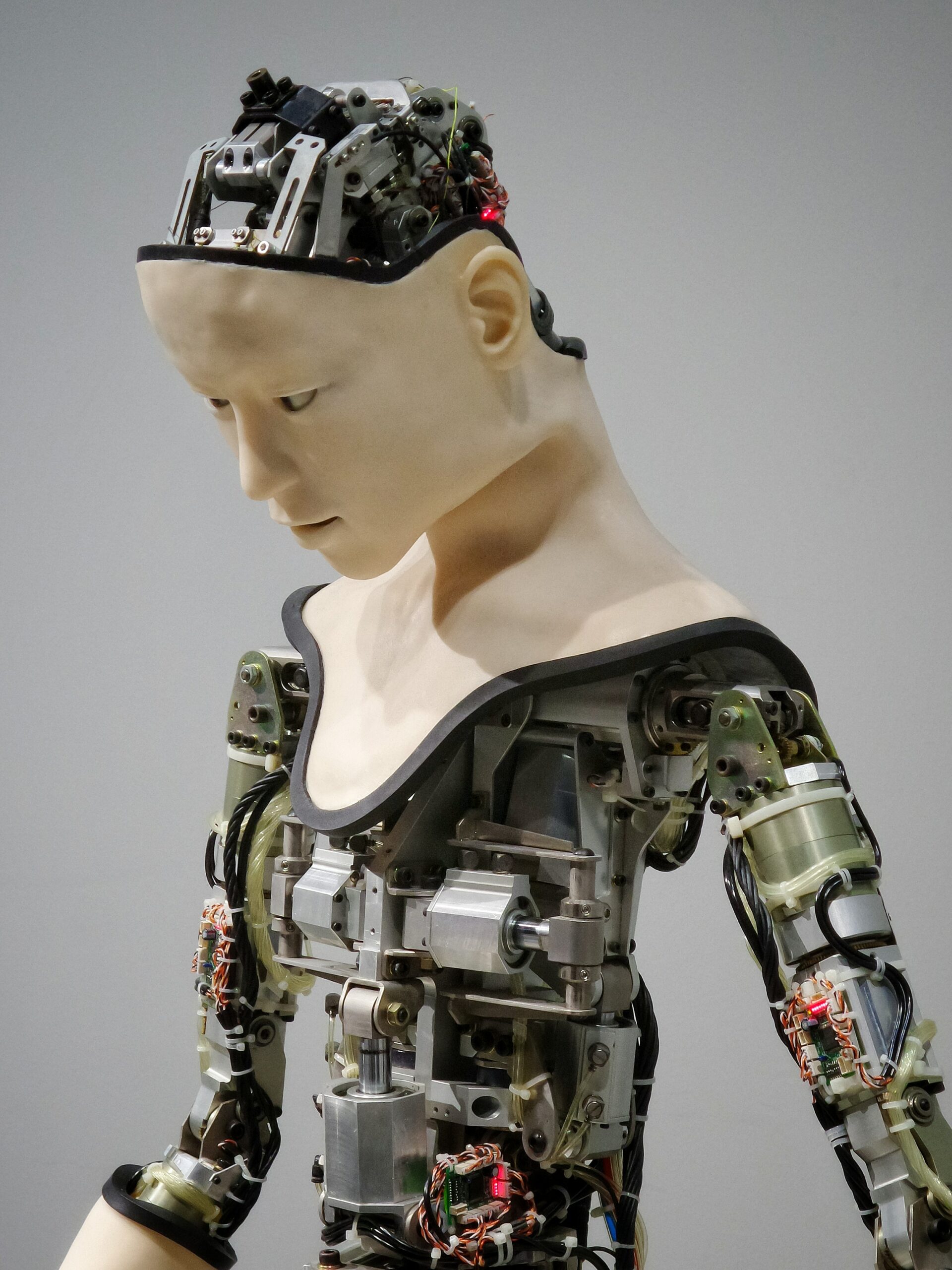

When I was a junior in college, I had a creative writing professor who discouraged his students from writing science fiction and fantasy. His rationale was that students who wrote speculative fiction would get too caught up in worldbuilding and forget the craft elements that were being taught. This is an extremely narrow-minded perspective that prioritizes a specific type of writing. Speculative fiction in particular––sci-fi, fantasy, horror––is in the process of being re-invented by people of color and queer people, with plenty of room for overlap. These genres are concerned with questions of humanity, monstrosity, and power dynamics while remaining accessible and entertaining. There is no shame in writing for a mass market, and there is no shame in using metaphors to explore deeper ideas about society. I have a passion for horror for this very reason.

The link between horror and queerness is a fascinating one. From classic monster movies such as gay director James Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein to the newly released Hellraiser with trans actress Jamie Clayton as the Hell Priest (Pinhead), queer horror explores what it means to be an outsider––and, in some cases, what it means to derive power from outsiderdom. In my own creative work, I am drawn to monsters for this reason. Monsters can highlight that the status quo is what’s truly monstrous about society. They have the potential to provoke a radical sense of empathy towards others and encourage solidarity as they work towards building a better world.

It’s important to not discourage students, especially those who identify as queer, from writing speculative fiction, especially if they use those genres to explore parts of their identity. In an interview with trans writer Ryka Aoki about her science fiction novel Light From Uncommon Stars, she says:

I don’t care how nice the new starship is, or how magical the new wizard school is––I would never want a world where someone like me would have to hide their identity, where queer love is relegated to whispers and subtext, or given “a very special episode”––yet never be allowed the dignity of the day-to-day. [. . .] I expect better from those who fill my world with dreams.

About her own novel, she adds: “I hope [readers] can feel seen a little bit more. I hope they can feel included a little bit more.”

4. Present queer stories that are not only about queer trauma.

When selecting stories for a creative writing class, incorporating the work of queer authors is important. Even more important is understanding that trauma does not have to be at the center of every queer story; there should be room for hope and joy as well.

In the Form and Technique of Fiction class I have just started teaching, I am introducing queer speculative fiction short stories alongside the more traditional textbook reading for the sake of introducing other genres beyond the traditional realistic and “literary” short stories typical to an introductory creative writing class. Part of the joy of reading and writing speculative fiction is presenting queer characters in stories that do not have to center a coming out experience or other experiences of queer anxiety, pain, or trauma. In books such as T.J. Klune’s The House in the Cerulean Sea or Ryka Aoki’s Light From Uncommon Stars, the characters have their share of baggage, but the emphasis is on community-building and the creation of a found family.

In my composition class, I shared the trailer and a review of nonbinary director Jane Schoenbrun’s new film We’re All Going to the World’s Fair in order to teach a lesson about quoting directly from a source as opposed to just paraphrasing. World’s Fair is a coming-of-age found footage film rooted in Schoenbrun’s experiences with dysphoria and using the internet to experiment with their identity, but it is not an outwardly “trans film.” Any chronically online teenager would most likely find themselves relating to it, regardless of identity.

Queer writers should be able to write stories that are not just about identity struggles. Those stories should be taught, not just for diversity’s sake, but to bring in a variety of perspectives that are not always heard from. A few of my favorite queer stories, collections, and essays are, in no particular order:

- Lee Mandelo, Summer Sons (Southern Gothic novel)

- Andrew Joseph White, Hell Followed With Us (YA dystopian novel)

- Aiden Thomas, Cemetery Boys (YA fantasy novel)

- Jordan Kurella, I Never Liked You Anyway (novella, retelling of Orpheus & Eurydice)

- Silas House, Jericho (short story)

- Lydia Conklin, Pioneer (short story)

- Chase Berggrun, R E D (Dracula retelling, whiteout poetry)

- Travis Lau, Paring (poetry)

- Julia Koets, The Rib Joint (creative nonfiction)

- Susan Stryker, Performing Transgender Rage (essay, part CNF, part trans analysis of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein)

5. Have an ongoing discussion about “writing the other.”

The question of who gets to write what, in terms of character-building, is complicated. Taking a class, or part of a class, to work through the complex aspects of writing a character who has a different identity from the writer can lead to a lesson in the importance of research and avoiding stereotypes. A few useful rules of thumb I have found are to run the character by someone who does share their identity (I have offered suggestions on classmates’ characters who identify as being under the trans umbrella). It also helps, as was mentioned in the previous point, to de-center that character’s pain while also taking into consideration how they move through a world which is not necessarily built for them. Where can they find joy and community?

Some more tips:

- Avoid stereotypes or tokenizing: The loud and effeminate “gay best friend” is not the only type of queer person out there! Having a queer sidekick looks like representation, but if they are only there to serve their straight best friend, that representation is only surface-level.

- Address intersectionality, privilege, and matters of safety: Depending on the environment, your queer character(s) may not be able to be out all the time, or they’ll have difficulties sharing their identity with others. They may use different sets of pronouns depending on who they’re with. YA novels are doing a great job with this. For example, Aiden Thomas’ Cemetery Boys follows Yadriel, a trans teen seeking acceptance from his traditional Latinx family. In an interview with NPR, he said that “I wanted Yadriel’s relationships with his family to reflect more of my personal experience––a family that isn’t intrinsically transphobic, just uninformed. There’s a learning curve.”

- De-center the character’s queerness: Create a fully fleshed out character the same way you’d create a straight character. In a novella-length draft I wrote, I created a queer character but paid almost no attention to that aspect of them. They were an artist, a comic book aficionado, a sibling, a friend––and they just so happened to be nonbinary.

Introducing ideas of representation, research, and above all, respect, can be mentioned in the first class and incorporated throughout the entire semester.

Introducing ideas of representation, research, and above all, respect, can be mentioned in the first class and incorporated throughout the entire semester. Is this an act of resistance? Ideally, no. This should all be completely normalized. We’ve come a long way, but we’re not finished yet. Continuing to cultivate empathy will lead to a sense of solidarity among everyone in a classroom. By introducing more queer voices into a creative writing classroom, it could be that queer students feel more welcome––and it could inspire cis students to try their hand at writing an experience different from their own, with sensitivity and responsibility.

H. Dietrich

H. Dietrich is completing their MFA in creative writing at the University of South Florida, where they teach composition and fiction. Their thesis is an urban fantasy/noir novel exploring themes of queerness, masculinity, and gender performance.