Hafiz Ahmed is at the top of Ms. Ramelize’s roster. On the first day of my residency at PS 64 in Queens, I announce the coincidence to the class: “Hafiz is also the name of a great poet!” His namesake beams back at me and Lukis asks if I’ll bring Hafiz poems to class. I agree, and week after week the students remind me, but I can’t think of any appropriate poems for six-year-olds. With two workshops left I leaf through The Gift in search of something first-grade friendly. Hafiz, a mystic Sufi poet, frequently addresses God as Beloved, Master, and Friend, often with erotic overtones. Other poems of his seem too metaphysical for kids, but eventually I find one that might work. “Sometimes I Say to a Poem,” translated by Daniel Ladinsky, begins like this:

Sometimes I say to a poem,

“Not now,

Can’t you see I’m bathing!”But the poem usually doesn’t care

And quips,“Too bad, Hafiz,

No getting lazy—

You promised God you would help outAnd he just came up with this

New tune.”

Apostrophe, personification, dialogue— I decide to try it (though I omit the racier lines in the last stanzas and read my own response instead). The lesson is straightforward: read the poem aloud, talk about techniques, and ask the students what they would say to a poem if a poem were a person. Hands fly and we fill the air with ideas. They get a kick out of it, and some take the opportunity to give poetry a kick.

David Cano writes: “Sometimes I say to a poem, ‘Leave me alone. I am picking some flowers and taking a shower.’ But the poem says, ‘If you don’t let me in, I will drop a wet hippo on you.’” Cassie Persaud begins by giving poetry a piece of her mind, but affection quickly overcomes impatience: “Poetry, you dance too much because you love to move too much. I love to dance too. We can dance together. . . . I love dancing with you.” Maya Pellot, in a pink T-shirt with “My little brother did it” written across the front, performs her poem for the class. She begins with an exasperated voice: “Sometimes I say to a poem, ‘Are you nuts? You cannot jump off the roof!’” Her volume drops as she speaks the poem’s doubtful reply: “I won’t die. . . . I think. Bye.” Here Maya pauses for dramatic effect, giving poetry time to plummet, then adds: “Ouch!” Her classmates burst into laughter, and I’m impressed—the lesson works. Even Hafiz Ahmed writes his longest poem so far: “Sometimes I say to a poem, ‘Go to the store and buy me a lemon!’ The poem says, ‘You’re welcome.’ Then the poem sings a blues song with a red violin.”

One of the reasons Hafiz’s poem inspires them, I think, is its invitation to be bossy—they light up and exchange wide-eyed glances when the speaker gets sassy. First-graders rarely get to give commands or talk back, so to play with apostrophe in this way is empowering—a chance to test their strength and flex their sense of humor.

Reading through this stack of poems later on, I wondered if I’d inadvertently encouraged slapstick over depth; sometimes the sillier assignments produce a lot of karate chops and poop. Amid the wackiness, however, glimmers appear. In Hafiz Ahmed’s piece, for example, the poem ignores the lemon-errand and makes music instead, or else completes the task and then laments its subservience. Whether it’s expressing refusal or regret, his poem has links to lyric tradition, and his use of color makes the poem a surprise.

I decide to repeat “poems on poetry” with the third-grade students at PS 25 in the Bronx. This time I lead with Hafiz’s poem and ask the students to suggest other approaches: “What are some other ways we might write poems about poetry?” Drawing from what we’ve learned over the previous eight weeks, we brainstorm possibilities on the board:

- a list of similes and metaphors comparing poetry to other things,

- an acrostic poem using “poetry” as the spine word,

- a short story about a character named poetry,

- an ode to poetry using apostrophe and alliteration.

The students are impressed with their list, which serves as a quick review of their expanding bag of tricks. Now for the magic.

During the second week of the residency, I see Miranda Avila wearing a weary smirk during an “I Remember” exercise. When I ask her what’s the matter, she replies, “It’s hard, Mr. Burgess. I’ve been through a lot in my life.” I brace myself for the worst but notice a growing grin as she recounts the time her cousin jumped off the bed with her ear in his fist. She shows me the scar where she got seven stitches. After swapping accident stories for a few minutes, I remind her that anything can go into a poem. This permission does the trick and she becomes one of the most enthusiastic poets in the class. On poetry, she writes: “Poetry is like me writing on a cloud that goes all the way in the sky. I could see God waving at me saying hello.”

Whereas Miranda imagines poetry as a message sent into the sky, Ivelisse Gil sees the poem as a received message: “Poetry is like the sky writes to me.” Selina Mejia describes poetry as a kind of enlightenment: “Poetry is like the sun shining in people’s heads.” Clouds appear in Deja Powell’s poem, but they carry inspiration: “Poetry is like rain falling on the paper every time you think of something.” Chantel Taveras’ poem echoes William Wordsworth’s definition of poetry as “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings recollected in tranquility.” “Poetry is like your emotions saying goodbye. Poetry is like a big wave in your heart. Poetry is like my mother floating in the bathtub.” These students are only eight years old, yet they intuitively understand things about poetry that remind me why I read, write, and teach.

Maybe these young poets have something to teach my older students? On a whim I distribute stacks of their handwritten poems to my students at Brooklyn College and ask them to read one aloud to the class. They’re immediately charmed by the illustrations in the margins and inventive spelling, and by the end of the read-around they’re genuinely amazed. “Are they really in third grade?” “How did you get them to write like this?” I tell them the truth: I taught a few techniques and forms, read examples aloud, and said, “Pick up your pencil and see what happens.”

Poets in college courses have more preconceptions about what poetry is or should be, and one of my goals as a teacher is to expand their notion of what’s possible by getting them to try new forms and experiment with language. Basically, I ask them to play. Kids already know how to play and their poems give us a nudge in a new direction. In Rida Bint Fozi’s response, you can see the adult’s anxiety easing into curiosity and wonder

Sometimes I tell a Poem,

“I wish I understood you better.”

The Poem caresses my hand,

soothes me saying,

“No, you understand me fine.

You just need more time

to discover my quirks.”

Then I ask the Poem

to gently rub my shoulders.

And it does

until the birds begin

to chirp outside.

Then it crawls out

to the fire escape

to see what all the fuss is about.

When the imperative is to understand a poem, one response is predictable: “I don’t get it.” Rida reminds us that poetry often resists immediate apprehension—reading involves patience, sensitivity, and maybe even bird watching. Peter Collazo took his poem home and returned with a piece that brilliantly articulates the role poetry can play in a writing curriculum.

Poesía

Its oxygen breathed

life into a lifeless

mind muddled with

structured paragraphs and

grammatical errors. Powerfully, it

pushed the pen towards paper until

they Eskimo kissed

swirling characters that

expressed in a non-express

manner, slowly shuffling

the hots from the nots then

disregarding hierarchical status

altogether.

The heralded thesis is

not welcomed to its

wordplay playful

party. Masked meanings allowed to

remain disguised without needing

methods for their madness.

YOU released mumblings that

gatekeepers deemed irrelevant, humbling and

heightening the confidence

within myself.

This language does not

suffice to thank

your overtime

underpaid contributions.

Gracias poesía por

rescatarme de las

cadenas de escribir.

Though I’d never specifically discussed the philosophy of Teachers & Writers Collaborative in this classroom, Peter’s poem echoes our mission statement. The “heralded thesis” isn’t so much dismissed as put in its place; if students don’t have a positive experience with writing, the process can seem “lifeless” and the product a mine-field of “grammatical errors.” As teachers, we value structure and grammar, and we want to teach our students to write with clarity and precision. But we also want students to see writing as a meaningful act of communication, and we look for work with style and voice.

Contemporary composition theory addresses the issue of writing teacher as “gatekeeper.” “Mumblings” were once struck down with the notorious red pen and few doubted it was the right thing to do. Then we realized that student writing wasn’t necessarily improving as a result of rigorous dissection, and we turned our attention from product to process. The work of Peter Elbow and others assigns “mumblings” an important role. With “free-writing” we allow our ideas to spill onto the page in an early stage of the writing process. Since many of us discover our best ideas in the act of writing, we shape our sentences from these tentative beginnings. And when we relax and give ourselves permission to make a mess, we become better writers in the process. How does poetry fit into all of this?

I echo the ideas of two Donalds. In his article “The Listening Eye,” Donald Murray discusses his evolution as a writing teacher. After years of diligently marking papers, he realized the importance of teaching students about the process of writing. Writing involves putting down something that doesn’t necessarily make sense and making sense of it, draft after draft. Like all writers, students learn to “follow language to see where it will lead them.” We might resist the process for many reasons or be convinced we have nothing to say, but once we sit and write, something happens. Having written, we often think to ourselves, I didn’t know I knew that, or I didn’t think I had it in me. Students who learn to trust that the process of writing will lead them somewhere become stronger, more confident writers.

Donald Barthelme, in his essay titled “Not Knowing,” explains that “writing is a process of dealing with not-knowing . . . without the possibility of having the mind move in unanticipated directions, there would be no invention.” Whether we’re teaching research papers, analytical essays, fiction, journalism, or poetry, the act of writing involves this movement from not-knowing to knowing. Since we know from our own experience that discoveries are made once the writing is underway, we should teach our students how to negotiate this not knowing— how to allow for uncertainty and trust that the process will take us somewhere.

The in-class poetry workshop models this dynamic in a playful, low-stakes way. We write together for five, ten, or fifteen minutes and something happens: a poem often appears. A student who says, “I don’t know what to write” before picking up her pencil is suddenly reading her poem aloud, and there are glimmers in it—a line, a phrase, an image, a bit of music. It might not alter the trajectory of the poetic tradition, but it might change her relation to writing. She might be less intimidated by not-knowing next time, and, as Peter puts it, let the pen “Eskimo kiss” the page.

I recently finished a year-long residency at PS 187 in Manhattan’s Washington Heights with students in grades five through eight. During one lesson, a seventh-grader named Eugene raised his hand and blurted, “What’s the point? Why is this important?”

For a moment I froze, my mind racing with possible replies. Eugene had been skeptical from the beginning—he often rolled his eyes and made sarcastic remarks under his breath. He was also charismatic and smart; others looked to him for cues and quieter kids cowered in his presence. Eugene’s question didn’t surprise me—it always seemed to be written on his face— but I wasn’t sure how to respond on the spot. I managed an adequate segue and moved on, but the moment stayed with me. Whether Eugene was throwing a jab or making a genuine inquiry, his question is a valid one.

Before we made our transition from poetry to fiction midway through the residency, I included the “poems on poetry” lesson. I deliberately avoided preliminary discussions about “what poetry means to me,” remembering that teenagers, like the rest of us, resent forced enthusiasm. Plus, I was genuinely curious to see what they’d write, and I didn’t want to influence their poems’ content or tone. My lead-in was essentially the same as with the third-graders; I asked them to suggest various approaches and then I read a few examples from other students. This openness might have intimidated students at the beginning of a residency, and this is the beauty of the “poems on poetry” lesson; after weeks of reading and writing poems most students enjoy the freedom to choose their form, to follow their words and see where they lead.

Though I had been entertaining doubts about whether I was reaching these junior high students (Eugene wasn’t the only eye-roller), the poems on poetry were proof that discoveries were being made beneath the teenage poker faces. I remember reading Carla Luna’s line over her shoulder: “Poetry is the adrenaline rush of a roller coaster in the safety of your own home.” Carla reminds us that poetry can whisk us off and quicken our pulse, but it can provide consolation and companionship as well. She continues: “Poetry is a hand when you need it most. Poetry is a safe haven away from all that is bad.” Nerelis Fernandez echoes this paradox in her poem: “When a tornado of emotions / Overwhelms you, / It will be your shelter, / Your basement. It is your heart, never / Knowing where it’ll take you.”

Some students have mixed feelings about the “trip” poetry takes us on. Christine Johnson gently cautions the wary traveler in her acrostic poem:

Pencils

Opening another world

Entering

Trying to figure out where you are,

wondering if you should

Retreat back to where you came from—

You lose yourself in poetry.

Christine follows this statement with a list of similes, as if compelled to continue: “Poetry is like a bigger world. . . . Poetry is like riding a cloud of thought.” If we temporarily lose ourselves in poetry, as Christine says, we end up in a larger world in the long run.

Raisa Feliz points out that the journey is into ourselves; we are the ones who expand. Her deceptively simple acrostic has profound implications.

Poetry takes you places.

Orients you to your culture.

Entertains you.

Transports you to your inner self.

Rotates your ideas and imagination.

Gives you reasons to say

Yeah.

Poetry can be entertaining, and it can also change your point of view. Once we change our perspective, we see and think in new ways. This new vision wakes us up to the beauty of the ordinary, which we affirm with the poem—more “reasons to say / Yeah.” Poetry can also allow us to perceive the mysterious, the hidden, and the implicit. As Samantha Olivieri puts it: “Poetry is a magnifying glass where the unseen shouts out.” For Kiara Newman, “Poetry is a flash— / It transports enthusiasm / and hope.” Marcel Johnson would probably agree: “Poetry is like a candle that flickers on and off / just like your ideas do.” Aleksander Popovic remarks on this shining quality, likening our minds to diamonds in his “Ode to the Poem.”

Where would we be without you?

Blank and dull

Seeing the world in black and white

Our minds would be gray

And easily molded like clay

But thanks to you

We see the world in every color

And our minds

They sparkle and shimmer like diamonds

And make us who we are.

Eugene’s question—“Why is this important?”—is a crucial one, and I think many educators share his skepticism. Teachers often see poetry as a filler or a treat, something squeezed into two weeks in April. The poems written in response to the “poems on poetry” lesson are evidence of what I’ve sensed for years—the value of teaching poetry and its potential to transform students into stronger, more confident writers. Early elementary students demonstrate that writing is an act of the imagination; we don’t need extensive vocabularies or mastery of grammatical rules to make something meaningful. These young poets also remind us what can happen when we stay open and give ourselves permission to write through our “not-knowing.” For survivors of the red pen or the gatekeepers’ criticism, we can learn a lot from these beginning writers. Play, it turns out, is serious pedagogy, and poetry can breathe life into any writing curriculum. In Peter Collazzo’s words, it’s time we acknowledge poetry for its “overtime / underpaid contributions.”

Hafiz Ahmed is the reason I first taught “poems on poetry.” Now it’s one of my best lessons, a favorite way to finish a poetry residency. Students have the opportunity to reflect on what they’ve learned from poetry, and we’re reminded of why it’s important. Thank you, Hafiz. Thank you, Eugene.

This article was originally published in the Fall 2008 issue of Teachers & Writers Magazine.

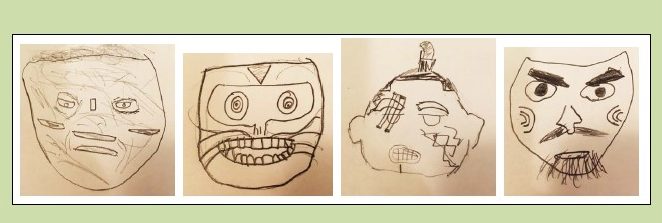

Photo (top) by Matthew Burgess

Matthew Burgess is an Associate Professor at Brooklyn College. He is the author of eight children's books, most recently The Red Tin Box (Chronicle) and Sylvester’s Letter (ELB). Matthew has edited an anthology of visual art and writing titled Dream Closet: Meditations on Childhood Space (Secretary Press), as well as a collection of essays titled Spellbound: The Art of Teaching Poetry (T&W). More books are forthcoming, including: As Edward Imagined: A Story of Edward Gorey (Knopf, 2024), Words With Wings & Magic Things (Tundra, 2025), and Fireworks (Harper Collins, 2024). A poet-in-residence in New York City public schools since 2001, Matthew serves as a contributing editor of Teachers & Writers Magazine.