One moment I’m standing in the mall, just waiting to pay for my cinnamon crumble cookies and Gatorade at a snack stand, and the next I’m on a potentially dangerous island.

Alexa, a high school sophomore

When I first started teaching 10 years ago, I had time to read student essays on the weekends. Now that I have a wife, a home, a son—I don’t have that time, or maybe I’m just not as willing to put in those extra hours. So what was I going to do? If writing teachers want to hold their students accountable for writing, teachers need to read the work. Imagine assigning a hypothetical three-to-five-page narrative with prerequisite drafts. With 150 students, that adds up to anywhere from 450 to 750 pages of student writing for me to read, about the length of novel. On top of planning, meetings, personal life, and required professional development—who has the time? Some saints still spend their weekends writing personalized feedback, justifying grades, and offering revision suggestions for all of their students. I do not have the time, so I have to rely on writing workshops.

In college, I studied creative writing. Every semester we had writing workshop, which meant everyone in the class wrote a 15-page story and brought it to class for a 90-minute critique. After my first critique, I felt physically sick seeing the grammar errors I’d made, my use of the passive tense, and the overly wordy exposition in my writing at the expense of clarity. My story, I think, was the worst story of the semester. No one could see my ideas through all the dirt and grime on the window. Before then, teachers had told me that I was a “good” writer.

PQP Feedback

University creative writing programs rely on the workshop method to teach writers. As iron sharpens iron, one writer chisels another. By the end of the second year of the program, I was runner-up for the fiction prize. Later, when I started to teach creative writing at the high school level, I wondered if I could adapt the usefulness of the workshop for my own classroom. Then, somewhere along the way, I learned about the PQP approach to offering constructive feedback.

P

Praise: What do you like about the work?

Q

Question: What clarifying questions do you have?

P

Polish: What do you suggest could improve the piece?

What I liked about this structure was that it framed the conversation in a simple and positive way. Also, the acronym stuck in my students’ minds. During the pandemic, my students typed the feedback to each other via our learning management system, but a worksheet could have sufficed if we were in person. I started PQPs between two “shoulder partners.” As students became more comfortable with the process, I expanded the groups to four students, trying to take the social dynamics of the workshop groups into account as I was planning them. Over the years, I have tried pairing accomplished writers with limited-proficiency writers or having groups of just accomplished writers and groups of just limited-proficiency writers, but I now think it is best to have a mixed grouping of accomplished, developing, and limited-proficiency writers. If our high-proficiency writers can be guided in how to give feedback, they can be leveraged to help their peers. This practice, of course, will help them critique their own work, but it will also help them develop the essential skill of providing helpful written feedback. How much of our professional lives requires the finesse of giving advice without offending our audience? Meanwhile, developing writers will learn from reading and critiquing the work of their accomplished peers.

Island Survivor

Perhaps the most successful writing assignment in my classroom is the Island Survivor Story in which I invite my students to imagine a fictional story of any genre around being stuck on a deserted island. Only the setting is fixed. Students enjoy the shared story aspect of this activity—some even become characters in each other’s writing. Before beginning the process, it is essential that teachers and students develop a list of norms for how to participate positively in the groups. There must be a foundation of trust. Then, through active listening, discussing, and critiquing with the PQPs, students will share in the process of improving each other’s work.

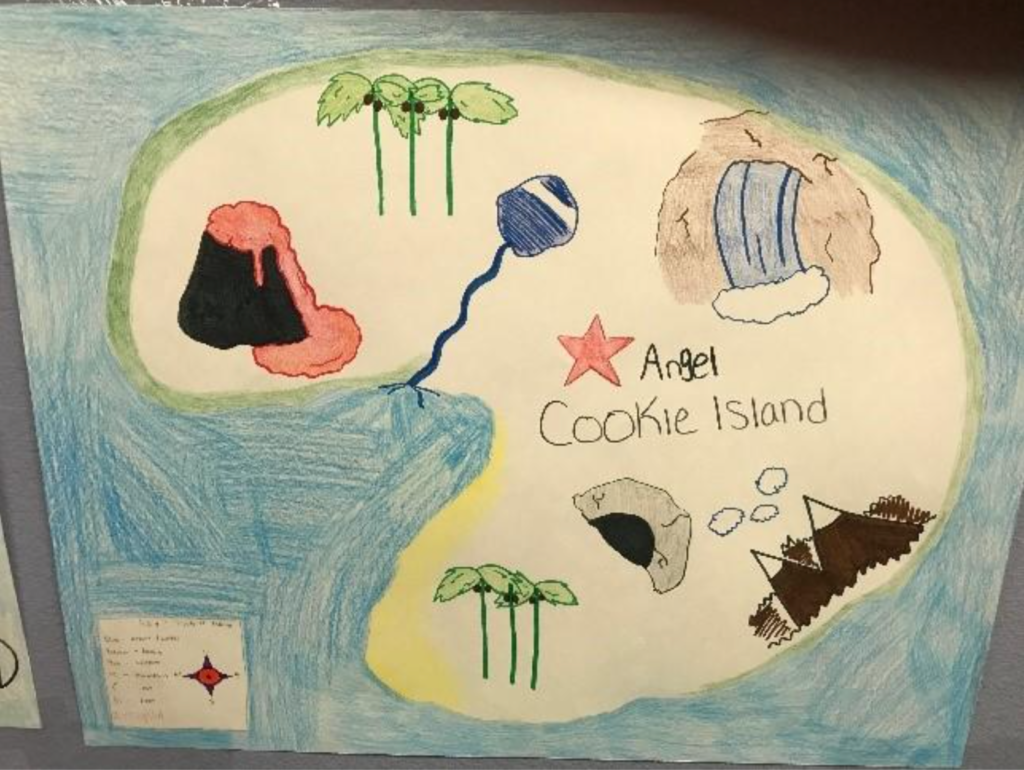

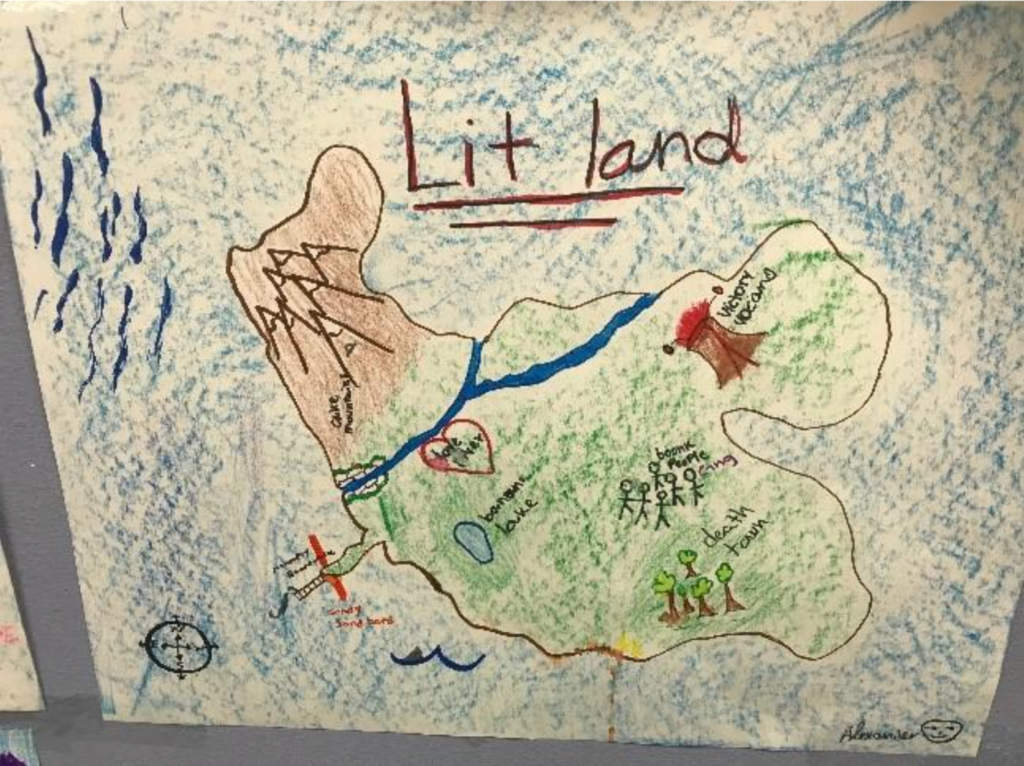

The project begins with groups of four students collaboratively brainstorming an island map with key island features: cave, mountain, water, land, trees, compass rose, map name (ex. Mystery Island). This collaboratively brainstormed island becomes the setting of their stories, and I pepper the maps of this setting around my classroom like wallpaper. These poster teams become the peer feedback groups for the writing assignment, and I find that the students are a little more comfortable with each other after this activity.

Prompts

The writing of the island stories is broken into chunks, called prompts, so that students get more opportunities for feedback.

- Prompt 1: Imagine that you are on your island. How did you get there? What do you see around you? What do you hear, taste, smell, and feel? Tell us the story.

- Prompt 2: Write 100 words minimum, exploring your island. Use some of the strong verbs from the handout to help you on your journey. Highlight at least five strong verbs in bold.

- Prompt 3: Meet your foil on the island. Show us the character by their speech, thoughts, effects on others, actions, and looks. Have a conversation with your foil. Remember to indent your dialogue. Each new thing said should be its own line.

- Prompt 4: Face a conflict on the island. Your conflict should be both internal and external. It could be a storm. It could be a monster. The internal conflict is what is happening inside your narrator’s head. You’ve already established the setting (the where and the when) and characters. Now it’s time for a struggle. It’s time for conflict. Your hero could fight a monster. Your characters could brave a typhoon. One of your characters could be hurt. The possibilities are limitless.

After responding to each prompt, the students write PQPs for their partners. When students are aware that their writing can be viewed and evaluated by peers, their engagement and effort increases; therefore, quality increases. I assign three PQPs for each student, and, to save time, I pick one at random to grade instead of all three. With my critical focus on feedback, I can be more evaluative without discouraging the writers in their creative work, and my students receive three times the feedback. The only problem is that I had to find a way to hold students accountable for writing peer feedback and not just saying simple phrases like, “I like the action,” or questions like, “How did you think of this story?” So I wrote a rubric that scores their PQP and provides direction for improvement. Here is the rubric and some excerpts of workshop interactions between students.

Peer Feedback Rubric:

| Criteria | Accomplished (100-90) | Masters (89-80) | Developing (79-70) | Emerging (69-60) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ideas | Feedback person makes thoughtful claims and questions. | Feedback person makes clear claims and questions. | Feedback person makes general claims and questions. | Feedback is very basic and not thoughtful. |

| Conventions | Feedback has no grammar, capitalization, or punctuation errors. | Feedback has very few errors. | Feedback has multiple errors. | Feedback is hard to understand because of errors. |

| Evidence | Feedback person gives specific evidence or examples. | Feedback person gives evidence or examples. | Feedback person gives little evidence or examples. | Feedback person does not give evidence or examples. |

Student Journal Sample

(Prompt 3):

The manor was huge so we all spilled up and searched for anything we could find. There was a loud boom that we all rushed over to see to find out what it was but nothing was there. As we continued to look for things I spotted something from the corner of my eye that I thought could help. I was in disbelief that I found the map of the island and there was so much more that we had to discover. “Phoebe look at what I found.” I said “What is it?” asked Phoebe “I think it’s a map of the island.” I said “No way, let me see!” in disbelief said Phoebe “This thing has to be at least 1000 years old it’s so brittle.” said Phoebe “It looks like a piece is missing, maybe we should go show the rest of the group to see what they found.” I said We met up with the others; Sora and Alexa, to show them what we found. Just before we could say anything they held up the other piece of the map and asked have we had seen the other piece. While the manor filed with silence we pulled out the other piece and the map magically glued back together and started to glow brightly. – Dynasti

Peer Feedback for Dynasti’s story:

P: I like how descriptive your journal is, “This thing has to be at least 1000 years old it’s so brittle.” It’s almost like I can picture an ancient map in front of me.

Q: Why were you looking for a map, and where does it lead you to? Also, who is the manor and what is his purpose in your story?P: One thing I noticed is that you would add periods instead of commas. For ex. “I think it’s a map of the island.” I said. The period should be a comma.

-Llelani

M.P. Vivian has been teaching writing at the secondary and post-secondary levels for over 10 years. He is a graduate of the University of Missouri’s MFA program in Creative Writing. Currently, he lives near Dallas, Texas with his wife and newborn baby. You can find him on Twitter at @M_P_Vivian.