We are always developing a lexicon for feeling; a language to express a nuanced, sometimes layered truth.

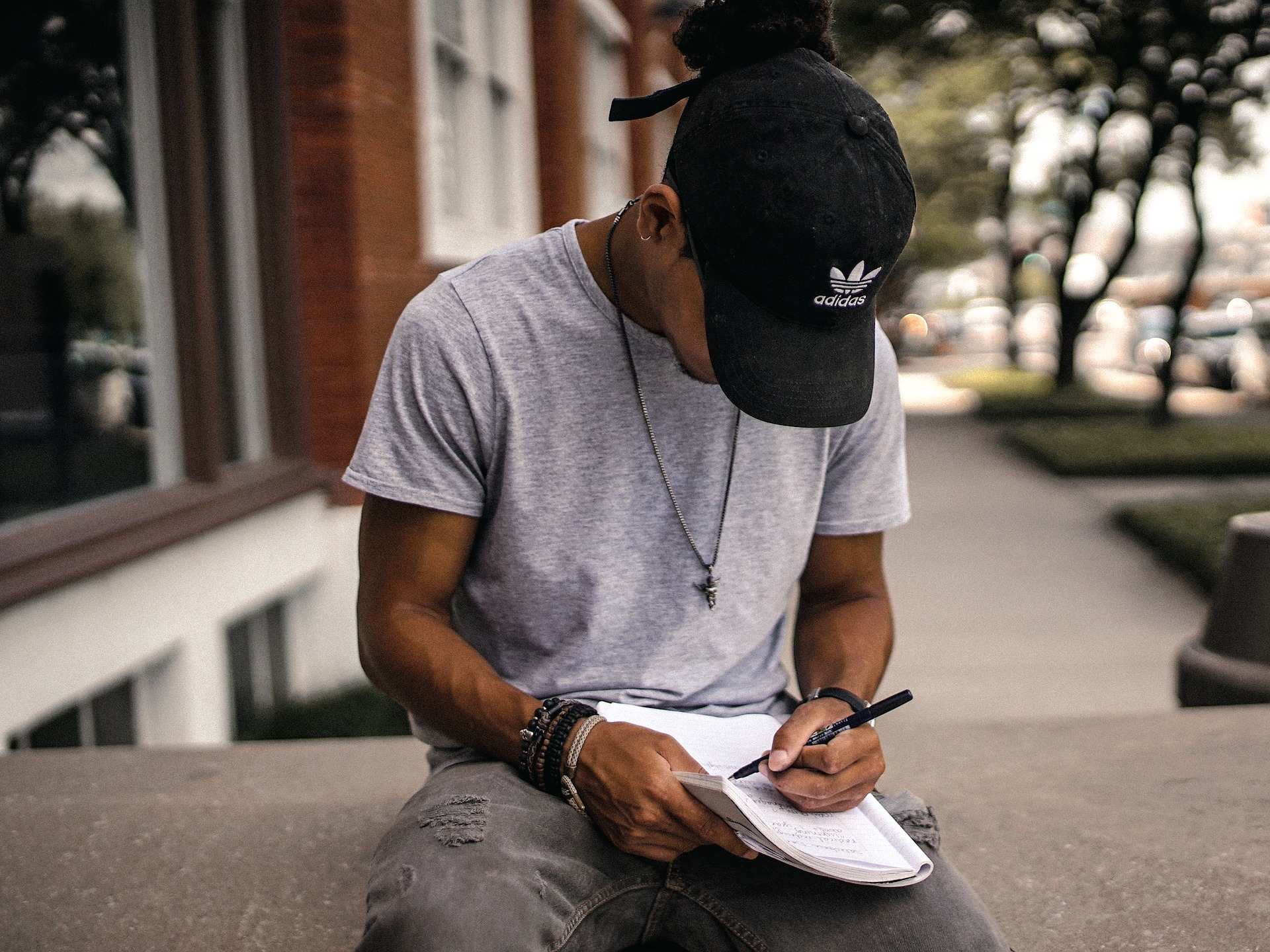

“I’m involved in something rather dangerous;” James Baldwin says in the opening of his Notes of a Native Son. “I think it’s always dangerous for a writer to talk about his work… It comes out of the same depths that love comes or murder or disaster.” As a young poet guiding younger poets, I find the difficult work of poetry does not stop at the writing nor the one-off recitation of it. We are always developing a lexicon for feeling; a language to express a nuanced, sometimes layered truth.

In the classrooms where I work I see young people navigating biases based on race, gender, sexuality, nationality, and other perceived notions of identity while being denied the basic tools of language and communication that would help them to do so. When instruction in grammar, punctuation, cursive writing, phonics, and other basics of literacy—not to mention art and theater—is being stripped from the curriculum, language—or rather access to it—becomes another one of the barriers that divide a room.

Teaching artists often find themselves left to do the work of language teachers, equipping a 9th grader with what they should have learned in middle school. Baldwin reminds me that as a black young man not unlike my students, the closer I get to the root of this issue (of who learned what, when & where), the further I am traveling back in time. The further back I travel in time, the more I am reminded of the humanity my body so easily loses.

In 2018, at New York City’s Queens High School for Information, Research, and Technology (QIRT) in Far Rockaway, I worked alongside English teacher Ms. Robinson in developing poetry workshops that were just as often focused on the racialized, state-sanctioned violence that is part of these students’ lives as they were on form. In these classes I saw how urgent the need for clear self-expression is.

The plan was for each student to use their poems to create their own individual magazine as their final project for the class. When you ask a 9th grader to write about themselves or about how they feel, however, particularly the boys, this required some digging. The 8th graders were, in general, quicker to talk about how they felt, to dive in to the writing and volunteer to perform. My 9th graders were drawn to using forms, perhaps because the forms gave them a structure to hold their emotions. These poetic forms— the contrapuntal, the palindrome, letters to our ancestors, and the tritina —gave them a space where they not only could write their own narrative, but create their own realms where they could respond to oppressions they had no other way to push through.

The tritina, a shortened version of the sestina, is a 10-line poem composed of three 3-line stanzas and a concluding line, called an envoi. The three end words of the first stanza are used as the end words of the next two stanzas, but in a different order. If the words at the end of the first three lines are 1, 2, 3, then the pattern of end words looks like this: 123 / 312 / 231. For the last line—the envoi—all three words are used in the same order as the first stanza, 123, but all in one line.

When assigning this form, I ask my students to choose their end words first, which allows them to fill in the blank slate of the poem with their own experience. Charles, an Afro-Latinx student at QIRT, tackled the subject of assimilation in his tritina, articulating the process of understanding what it means to be “American,” or “African”, or an “African-American Male.” He writes of his reality, of being perceived as African-American before African and, yes, sometimes before American, but always as “dominant” and male:

African American Male

I was younger and I didn’t realize what it meant to be African

I thought I was just straight American

What I knew wouldn’t change was that I was a male.

People wanted to be that dominant, oppressed, oppressive male

Everyone wanted to be American and live the dreams of Americans

Too bad they had to face the truth they weren’t just American

They tried their best to fit in because ‘they’ was a male

They got treated differently now they had to accept ‘they’ was African

Now they had to fit in with their own and be African-American Males

Charles, at first, was often more comfortable with me reading his poem, as is the preference for a lot of 9th graders. I’m left wondering if this reluctance is also a kind of assimilation or silencing: to be enthralled with the work but prefer to be sitting, or quiet, or disembodied while another older body speaks for us. Is this not how so many of us, even as we grow, survive?

In and out of the classroom, my experience at QIRT reminds me that poetry serves as a body that gives context, subtext, and meta-text to other bodies; that connective, ancestral, what Audre Lorde might call psychic, real-life, and actual tissue lives beneath the surface of the work, and beneath the complicated ‘quiet’ of a student.

Trace Howard DePass is the author of self-portrait As the Space Between Us (PANK Books, 2018), which was a finalist for the 2019 Eric Hoffer Book Prize. He served as the editor of Scholastic’s Best Teen Writing of 2017 and as the 2016 Teen Poet Laureate for the Borough of Queens. His work has been featured on screen and radio—including BET Next Level, Billboard, Blavity, Poetry Foundation, Ours Poetica, and NPR’s The Takeaway—and in print in SAND Journal, Entropy Magazine, Sonora Review, Platypus Press, Split This Rock, The Poetry Project, Bettering American Poetry (Volume 3), and the Academy of American Poets Poem-a-Day series. DePass is a fellow with Poetry Foundation’s Teaching Artist Project and Poets House, and a Teachers & Writers Editorial Fellow.