The Lark Essays: An Introduction

On November 13, 2014, “Two Truths and a Lie,” a writing workshop I teach in NYC, was held up at gunpoint. After the robbery, the class became the invisible center in a maelstrom of tensions around the New York Police Department’s Stop-and-Frisk policy, gentrification, and the role of police in communities. Much of what was written in the media about us and about the robbery was not true. Most of the solutions to “crime in the city” that were discussed in relation to the robbery did not reflect our beliefs.

The media, including the New York Times, covered the class in skewed ways, placing us as simply a marker in the inevitable path of gentrification. Facebook and neighborhood blogs reacted with racially charged remarks and calls for more police presence. My students and I bristled at such simplified answers that were nothing more than a shrugging of the shoulders or a heightening of violence—a refusal to look at all the reasons why this young man would need to walk into my classroom with a gun.

As writers and teachers, my students and I had a choice. We could allow our experience of that night to be misused or we could create and share our own narratives. As teachers in NYC, we have seen young boys of color suspended as early as middle school, a few of many affected by the school-to-prison pipeline. We have witnessed the effects of Stop-and-Frisk on students’ abilities to focus in class. We’ve felt the build-up of rage in the eyes of the public at the list of names as long as generations of young black men killed with no justice served. For many of our students, both high school and undergraduate, Stop-and-Frisk, police brutality, and lack of justice were not issues in the news, they were personal events and obstacles in their lives.

Why did this young man walk into our classroom ten minutes before class was about to end? These three articles by Soniya Munshi, Nina Sharma, and me explore this and other questions about the robbery and its after-affects from multiple perspectives.

One.

The young man walked in ten minutes before class was about to end. Daylight Savings had just begun, so it felt extra dark at 8:50 at night. My back was to the door. Later, I was grateful I had chosen this seat, so I, the teacher, could be right next to him, rather than anyone else.

I had paused extra long before choosing my seat that evening. It was one of the teaching rituals I practiced with this class: I found that even without assigned seating, people gravitated to the same spots each week, and when I switched it up, others did as well. We were shaken out of our patterns, and musical-chairs-style laughter often erupted at the beginning of class. We liked each other, had an ease and comfort.

At first, I thought the young man had come in to hit on us—it happened often when our writing workshop let out and we spilled into the street. Our class was filled with intelligent, talented writers: a radical librarian, a journalist who worked with India Abroad and the Asian American Writers’ Workshop, a professor at Borough of Manhattan Community College, a thoughtful school counselor, three poets. It was, in short, a night I looked forward to every week.

I had been teaching “Two Truths and a Lie,” a workshop on memoir and autobiographical fiction, for the last few years. This Brooklyn group had been meeting since April. Every time one cycle ended, we decided to add more classes. Now it was November, feeling like the beginning of winter, and a stranger had entered our space: the side room of a café in Brooklyn.

He was tall, standing right next to me, and I did not at see at first that he was wearing a mask. It wasn’t until a second later when he pulled out the gun—silver, looking like a prop from an old Western—that I realized this was not a man who was going to ask us for directions. This was not a man who was going to ask us out.

I looked at my students. They were all turned toward me, their faces asking if this was really happening. It was their faces that made me realize it was. The sound and action that had gone out of sync the moment he entered suddenly synced again.

He whispered, “Put your laptops in the bag. I don’t want to kill anyone.” I hadn’t even heard him the first time. Now I realized this was the third time he was saying it.

Two.

Later in the evening, the café filled with police, the class stood in a circle and laughed when a student said, “My favorite part was Bushra’s face! Did you guys see her face? She literally rolled her eyes…there was no fear at all, it was just like, ‘Seriously?’ You were just so annoyed….”

It was true. I hadn’t felt fear. Instead, I had heaved a sigh of exhaustion, one that came from being a broke, exhausted new mother who did not need this, and then, my Queens had kicked in. I’d snapped my laptop shut and made the kind of face a teenage girl would make. Sucked my teeth and rolled my eyes. I did it from instinct and memory, but also for my students. I hoped it would make them laugh inside, and I knew he could not see my face, just as I could not see his.

Fear did erupt in me in the nights after the robbery, but in the moment I had been calm. His youth, height, build, and quiet demeanor reminded me of the young men who helped me get my daughter in her stroller up and down the steep Church Avenue staircase whenever I needed help. It reminded me of my work as a teacher in NYC public schools where the presence of a young black man at the front of my classroom was familiar.

It was only the gun that felt surreal and strange.

It seemed strange to him as well.

His hands were shaking.

Three.

I was the first to put my laptop in the bag. In a way, I was relieved I had brought my computer. I could not tell my students to hand over their laptops without doing the same. What the man was pulling out of our hands were not machines, but manuscripts we had been sweating over, volumes of writing that had never seen the light of revision. Even with our hard drives and back-ups, there was no real way to recreate the totality of what we were about to lose.

I had brought my computer that night because I wanted to share a movie clip from Jim Henson’s The Muppets Take Manhattan. Most of the workshop members were second-generation Americans—of Bengali, Pakistani, or Indian origin. They either spoke another language or were raised by someone who did. One of the questions that often came up in our writing was how to render the in-between languages that formed when going back and forth between English.

It was while watching the Muppets that I found an example of newly-learned English rendered with poetry, originality, and respect in the character of Pete, the diner owner. When Kermit and the gang are struggling in their new lives in the city, when they cannot afford to eat. Before giving them all soup on the house, Pete tells Kermit: “Hey, I tell you what is. Big city, hmm? Live, work, huh? But not city open. Only peoples. Peoples is peoples. No is buildings. Is tomatoes, huh? Is peoples, is dancing, is music, is potatoes. So, peoples is peoples. Okay?”

Four.

In the days after the robbery, friends, family and the Lark Café community helped us raise money to replace our computers. At the same time, Facebook and the comments sections of our neighborhood blog filled up with inflammatory statements. Narratives were spun to heighten arguments about Stop-and-Frisk, gentrification, and the role of police in neighborhoods. Some residents called for greater police presence, making broad generalizations in which the term “locals” was coded to mean black and criminal. Some wrote that the robbery was just a “normal” part of gentrification.

It was true this area of Flatbush was gentrifying quickly, and the rise in rents was leading many of us who were not rich to breaking points, but when people shrugged and said, “This is just what happens when neighborhoods change,” I felt it was a cop-out, a way to do nothing about the underlying issues. It sounded too much like the arguments I had heard to fuel the “War on Terror” when people said, “The Muslim world just hates us for our wealth and freedom.” In both cases, police and military presence were pushed as the solution.

Ten out of the eleven students in Two Truths were South Asian, and as a class, we felt our fraught position in the racial politics of both police harassment and gentrification. We felt ourselves allied with all people of color, but we also knew we were considered a “model minority,” a standing in opposition to the brown and black folk who were here when we arrived. In his historic book The Karma of Brown Folk, Vijay Prashad traces the connected history of people of color—how South Asians are pitted against African Americans specifically. Post-robbery, we were placed again in this painful position.

Five.

We held our next class in one of the student’s apartments. She was one of the four who had had her writing stolen. Although she was deeply shaken, she opened her home to us. We were relieved to see each other again. Just as we felt unmoored outside of class, simply holding class again helped us find our ground.

Before we began, we did a check-in. I started out the class by asking about the dark and the light, an opener we had used since Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights: as the days got shorter and the nights longer, we’d start the class with what was dark and light in our lives. Often it was heavy versions of both. It made sense to use this prompt again.

For the dark, many of the students talked about how the worst trauma had happened after the robbery. We recounted together the story of our interaction with the police. Two of the students had used a Find My Mac app to track their stolen devices. The tracker revealed the computers were already in a different neighborhood, but when they shared this with the officers, instead of following this evidence, the police milled around the café asking us the same questions over and over.

When the head detective arrived, I brought it up. “They tracked the computers to an actual building in another neighborhood. Is anyone going to go to there?”

The detective shrugged his shoulders and said, “It’s not like the old days when you could just go and knock down people’s doors.”

I exchanged a look with a student who was standing next to me. The detective noticed and started backpedaling, “The city brought this on themselves.” I realized later, he was referring to the criticism police were receiving for Stop-and-Frisk.

A few minutes later, the police rushed two students out, saying, “We have someone to ID. Hurry, hurry.” They were yelling, rushing, acting urgent. I wondered how they had someone to ID when the man had worn a mask and we had told them we couldn’t ID anyone.

There were tears in my students’ eyes when they returned. They had sat in the police car as the police pulled over a young black man and his friend while they were walking down the street, stopped them, and frisked them. This student had often been on the other side with boyfriends and friends—she shrank back into the police car, horrified.

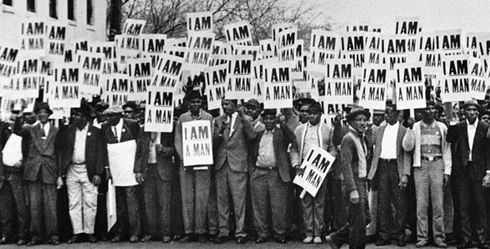

During this same dark and light go round, the young man’s identity kept coming up. As if by removing his mask we could free ourselves of the memory of him. There were so many imagined versions of who he could be, I started to think of how, as a teacher, I could use the opening of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. Published in 1952, this novel was a radical piece of literature told from the point of view of a black American man. I paraphrased the opening for my students and then went home and found the full quote. I decided to bring it in as a writing prompt for our next class.

The novel begins:

“I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe, nor am I one of your Hollywood movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, of fiber and liquids—and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves or figments of their imagination, indeed, everything and anything except me.”

The next week, now a band of traveling writers, we met at the Asian American Writers’ Workshop. During our dark and light check-in this time, the overwhelming emotions were the lingering fear we were feeling, accompanied by immediate shame and confusion at not being tough, of being afraid. Half of us had grown up in NYC from birth, half of us were transplants who had lived in the city for decades, but now we felt jumpy, afraid to turn corners. We felt unmoored, as if our sense of home had been stolen.

Our conversations led naturally to the two writing prompts I had prepared. I had written two quotes on pieces of paper. I told the students we would write based on what came up for us. I passed the first slips of paper to the right—the Ellison quote. They nodded, understanding my point.

Then, I passed the second quote to the left. I had folded the slips of paper in half. As the class opened them, I saw laughter begin to appear on their faces, a wave of smiles as they read the affirmation, the punch line of the joke I had been waiting to tell them for days.

It was Pete again, from the Muppet movie: “Hey, I tell you what is. Big city, hmm? Live, work, huh? But not city open. Only peoples. Peoples is peoples. No is buildings. Is tomatoes, huh? Is peoples, is dancing, is music, is potatoes. So, peoples is peoples. Okay?”

We thought of all the friends, family members and strangers who had come through for us and smiled.

Seven.

By our last meeting, the streets were on absolute fire. A grand jury had decided not to indict the New York City police officer who had choked Eric Garner to death, even though the entire event had been caught on video. Students arrived to class from protests in all parts of the city. One never arrived because he had been arrested for an act of civil disobedience.

In our last class, we talked about the ways our robbery was being used to bring more police presence into our neighborhoods and how we had actively fought this in our conversations in person and on community boards, how this had exhausted us beyond anything.

I shared with them a comment from a woman on a community list-serve for mothers, one I left soon afterwards. She wrote that she had seen progress because she had come back from a Town Meeting and seen the police arresting a young man on Church Avenue.

I went cold and responded, “Just because the police have a person in handcuffs does not mean they have arrested a ’guilty‘ person. I am a mother in the neighborhood. I was the person who was robbed at the Lark and the police action on the night of the robbery, and the racist and inaccurate remarks they made throughout the night, made me truly question their ability to make this a safer neighborhood.”

I was thankful when two other mothers echoed my opinion.

Eight.

When the young man started to leave, my phone was already in my hand. Seeing me dialing as he walked out the door, he said, “Don’t call the police”—but he said it half-heartedly, as if repeating lines from a script for a part he really had no interest in playing.

I did regret my decision. I was thinking of my students’ unfinished books, flying away in the thin gym bag the young man had put our laptops in. I was living in a fantasy to think there could be any kind of happy ending. The news was filled with images of black men being murdered. This young man was threatening our lives, but he was also risking his own. In some ways, I am grateful they did not find him. His life is worth infinitely more than any material possession.

Of course, I do not know truly why his hands were shaking—or anything that was going through his mind. I don’t know what he felt about our community, our neighborhood, and his place in it. All I know is he needed the money. This is the one fact I can say with certainty, and the answers to the whys of why he needed money require us to turn the knapsack of this whole culture upside down and shake it out to see what’s at the bottom.

Thank you to the readers: Ben Perowsky, Anastacia Holt, Nina Sharma, Sally Lee, Naomi Gordon-Loebl, Adeeba Rana, and David Stoler. Thank you to the Two Truths Class; Kari Browne and the baristas at the Lark Café; and all the friends, families and strangers (like Pete) who helped us replace our computers so we could share our version of the story.

The Lark Essays

Additional Resources on School to Prison Pipeline:

- https://www.aclu.org/school-prison-pipeline

- http://www.tolerance.org/magazine/number-43-spring-2013/school-to-prison

- http://www.pbs.org/wnet/tavissmiley/tsr/education-under-arrest/school-to-prison-pipeline-fact-sheet/

Additional Resources on Stop and Frisk

- http://newsone.com/2298223/pedro-serrano-stop-and-frisk-nypd/

- http://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2014/12/26/chart-of-the-week-63-of-white-people-are-wrong-about-ferguson/

- http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/05/movies/the-house-i-live-in-directed-by-eugene-jarecki.html?_r=1&

Rehman’s dark comedy, Corona, was chosen by the NY Public Library as one of its favorite books about NYC. She is co-editor of Colonize This! Young Women of Color on Today’s Feminism and author of the collection of poetry, Marianna’s Beauty Salon, described by Joseph O. Legaspi as “a love poem for Muslim girls, Queens, and immigrants making sense of their foreign home—and surviving.”

Her new novel, Roses, in the Mouth of a Lion, is a modern classic about what it means to be Muslim and queer in a Pakistani-American community.