Caroline Cabrera is the Education Coordinator & Managing Editor of O, Miami. She is the author of the lyric essay collection, (lack begins as a tiny rumble) from Tinderbox Editions, as well as three poetry collections, Saint X (winner of the Hudson Prize from Black Lawrence Press), The Bicycle Year, and Flood Bloom, and two chapbooks, The Coma of the Comet (winner of the Burnside Review chapbook contest) and Dear Sensitive Beard (Dancing Girl Press). She holds an MFA in Poetry from The University of Massachusetts. She is the founder and editor of Bloom Books, a chapbook imprint at Jellyfish Magazine and the co-host of the arts advice podcast Now that We’re Friends. Caroline Cabrera’s work as an educator is grounded in her Miami community with projects such as Wheels and Words which displays student writing on Miami public transit and work through the Poetry Coalition adding braille poems to Miami-Dade county parks. For Teachers & Writers Magazine, Caroline and I talk about the interaction between poetry and place, from the environment and climate change to civic publishing projects. We discuss the importance of showcasing student and community writing publicly and all the behind-the-scenes work—by educators and arts organizations —it takes to get it done.

– Donnie Welch

Donnie Welch: Hello! Tell us a bit about O, Miami and what you do there.

Caroline Cabrera: O, Miami is an organization in Miami that is equal parts poetry and Miami. Our name is the address to the beloved. It’s the poetic address O, and our beloved is Miami. We’re all about poetry and place and different ways that we can make a more equitable narrative of Miami by elevating voices.

Our philosophy is that Miami is the most poetic city in the world. We don’t need to bring poetry in from anywhere. We just need to put a mirror up and reflect back what the poets in our community are already saying. And from our perspective, everyone in our community is a poet.

I work on our education and publishing projects, but we’re kind of all hands-on deck for our April Festival as well. Our education programing, which is really my main focus, has a pretty extensive writers in school program that we’ve been expanding and we also do a lot of community based educational programming with workshops and things of that nature.

We’re a small team and no one’s in a silo, so we are all kind of working on everything together to different degrees. Sometimes I’m selecting proposals and copyediting. Sometimes I’m at a school hosting a pizza party. Sometimes I’m in the classroom teaching. I like to make sure I’m still grounded in the classroom.

Donnie Welch: Do you have a favorite poem to teach?

Caroline Cabrera: I teach Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art” with a book of her journals called Edgar Allan Poe & the juke-box that has something like 34 drafts of that poem, and I bring the first draft and the final draft to my students to show revisions.

I was first doing this in college essay writing classes, so like freshman comp, and I would bring it in at a time when students were feeling really bogged down by revisions. And show that this poem is something that started strong and then went through so many iterations and became like this different animal almost.

I love that. I love how transformational the process is and how it really makes students take heart. Then they also just want to talk about the poem because it’s beautiful, which is exciting to me.

Donnie Welch: Access to 34 drafts is such an incredible insight to share too! And yeah, not only is the poem beautiful, but it’s pretty canonical. A lot of students have probably read it in high school.

Caroline Cabrera: Exactly.

Donnie, it doesn’t become a villanelle till like draft 20 or something. It’s like a free verse poem. I — I got chills just telling you about that. It’s so amazing. It’s so beautiful.

I love teaching revision too and it’s so hard. It can be really challenging to teach at any stage. People get very attached to their first thoughts and very precious about their first thoughts.

Donnie Welch: On the note of poetry, we’ve talked a bit about seasonality before and it’s something that really affects me and my writing. How does it enter your work, especially in Miami where seasons are much more subtle?

Caroline Cabrera: It affects me a lot. My poetry is very much based in the natural world and what’s happening in the natural world around me.

My transitions back from more seasonal places were very jarring because I grew up down here. So, you know, I was used it. But then moving back from Massachusetts, moving back from Denver, that first year back is like, “oh my God, like where am I in time?” But I think it just makes you an even better observer. I remember telling a friend who has always lived in places with pretty dramatic seasons, that the seasons are about what’s blooming. Something’s always blooming.

Right now, in my neighborhood, the gardenias are blooming, the tabebuia are blooming. But I know the jacarandas are going to come soon, the poincianas after that, it’s just being really in tune with all the little things and being really in tune with the angle of the light in the sky. There’s a way that the sun feels in November that’s very different from the way the sun feels in March.

And as the climate changes, things are blooming earlier. When I was a kid, poincianas always bloomed in July, and the past few years they have been like blooming in May and June. Mangoes, I mean, the mangoes are already all covered in blossoms.

I’m like, “Man, these are going to fruit before July!” Everything’s kind of shifting back.

Donnie Welch: Do you see climate change making its way into your work more and more recently?

Caroline Cabrera: I honestly haven’t been writing quite as much, but one of the pieces I’ve worked on recently is a kind of haibun journal. And, what we’ve talked about so far about observing, it’s like that to the -enth degree. Because all I was doing while I was pregnant was just walking the same neighborhoods and noticing everything, you know, noticing the trees and little things like the incremental changes and the seasons creeping in in different ways.

But also the water level rise because increasingly we have king tides that will flood the streets. And there are things where you notice, “Oh, the river smells weird today.” And when I say the river I mean the New River, which is the intercoastal, what we call the Intercoastal in Florida. It’s like a brackish, manmade waterway. But when you live in these little places around the New River, there’s flooding and suddenly parts of your walk are underwater.

Then also the looming threat of a bad hurricane season because we’re overdue. I just think when a hurricane can come ruin your land and your home. I don’t know — it’s just everything’s been very tentative in Florida.

Donnie Welch: Last year we collaborated on a project at the intersection of environmental and disability justice for the Poetry Coalition. It sought to address coastal resiliency and flooding with Mangrove planting and engaging disabled youth in the restoration process. This year the series’ programming theme is “The future lives in our bodies: Poetry & Disability Justice.” I’d love to hear what y’all will be doing!

Caroline Cabrera: This is a project that was proposed to us by a community partner. She’s an educator at the Lighthouse School for the Blind and Visually Impaired, which is a local institution, who we’ve worked with before. Her name is Emily Nostro, and we’ve done projects with her in the past. We did one a few years back called Secrets Sonnets where she made these beautiful braille sonnets. This project will be carried out by her colleague Ashlee Partin.

She approached us about doing braille poetry signs in parks in Miami-Dade County. So that’s something we’re collaborating on at the moment with her colleague Ashlee Partin and we’re using poems from our archive.

O, Miami has a huge archive of work. When people send poems for our ZIP CODE initiative or other open calls for work, or if people write poems in our workshops and share them with us, we add everything to our archives so that when we do future public art projects, we’re able to find work that speaks to the community. In this case, we looked for poems that used non-visual imagery.

So, really short poems, some of them from zip odes, that have these really rich sensory details that we’ll be translating into Braille and installing onto signs.

Our philosophy is that Miami is the most poetic city in the world.

Donnie Welch: That project sounds incredible! It’s also really cool that y’all have such a rich archive to pull from, must be such a resource!

Caroline Cabrera: Such a resource, yeah. And when we use this work it’s really exciting, especially when we use our youth work, the student response is just so amazing. The kids will say things like, “It kind of makes me feel like I’m a little famous.” They get this little boost and they take their poetry real seriously.

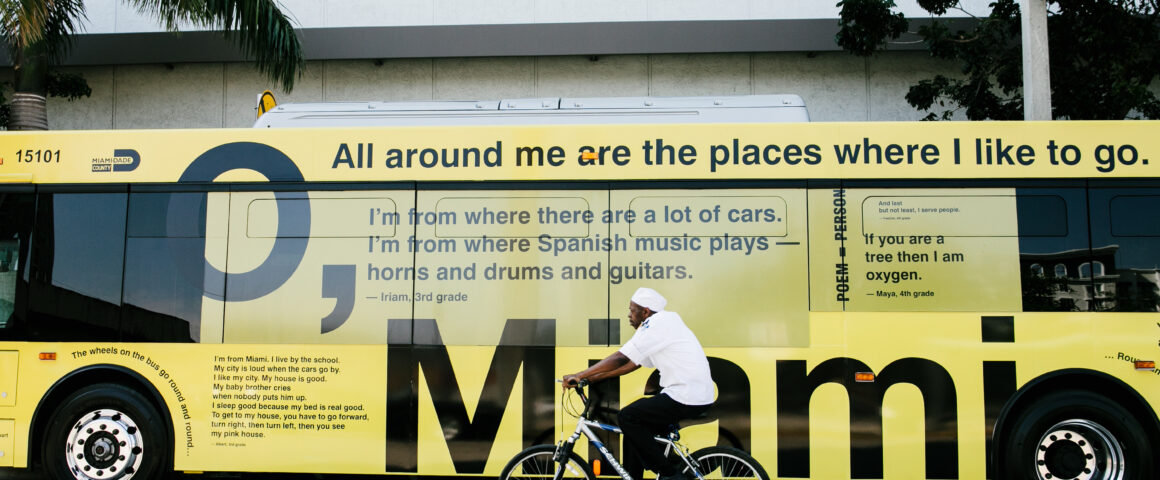

Donnie Welch: I love that, everyone deserves a self-confidence boost. You all do a lot of work in public places with student work like on public buses with Wheels and Words and on fences with Chain Letters, do you have a specific goal for these projects?

Caroline Cabrera: I think our goal is that these poems can be a kind of love letter to the neighborhood. That this is a chance for these student voices to be elevated and a moment to spark joy, spark empathy, and spark creativity.

My goal is that you see a poem on the fence or you see a poem when you’re sitting on the bus and you’re like, “Huh. What would I say?” And whether they write it down or not, that people walking by or driving by or sitting on the bus are crafting their own little poem about Miami or their own little “Joy Is” poem or whatever it is in their head.

Donnie Welch: How do you even begin to approach a city and ask, “Hey, do you mind if we wrap your busses in a student poem?” Or “Can we add a giant mangrove poem mural to the side of your school?” How do conversations like that begin? Any strategies for orgs trying to do the same?

Caroline Cabrera: Something that’s kind of like the magic behind O, Miami is that because we are such a small organization, we depend on community partnerships. And because we open up the festival to the community, we have the chance to meet people who work in so many different places all over the city, doing so many different types of things.

And we’re just constantly building this rolodex of people in Miami who do this, this, this, and this. We’re often just pulling from our contacts on former projects and asking, “Hey, do you know anything about this? Or do you know anyone over here?”

Honestly, that’s how our education programming has grown as well. When we get in with a school, it’s usually because we have an advocate there in some way, whether it’s a parent who advocates for us to the principal or the principal at the school used to be the assistant principal at a school where we did poetry. The challenge, which is totally understandable, is to convince the principal that it’s worth interrupting instructional time for what we’re going to bring.

We’ve been really successful at just kind of mining our contacts like, “Oh, this is the person who took one of my workshops and now she’s the media specialist at the school. So we’ll try to make a contact there.”

Donnie Welch: It seems like two big through lines in the success of your community work: one is finding an advocate. The other is the importance of documentation, whether it’s a contact list or an archive of work to pull from.

Caroline Cabrera: I think too, by virtue of necessity O, Miami has to trust and collaborate with people.

It’s impossible to produce what we do without really trusting our teaching artists. My experience as a teaching writer at first was so empowering. Once O, Miami got to know me, once they saw me in the classroom, they were like, “Yeah, you want to do a workshop for adults? Of course, we trust you. You can do it.”

And that’s the way we operate a lot and one of the ways we expand. We have advocates in educational spaces, we have advocates in the arts spaces, and it happens all the time that people will be like, “You know what, here’s a person I know who should know in Miami,” And they broaden us into their friend network that way.

We have to collaborate, we have to trust and then because we’re vulnerable in that way, it has all these amazing rewards

Donnie Welch: What’s on tap in this year’s festival for O, Miami education?

Caroline Cabrera: We have a project that I’m super excited about that we’re calling Writing Buddies. At one of the schools where we’ve been embedded for a while and where we have a legacy with the students, we’ve been training our fifth graders on how to instruct poetry to kindergartens. This is a pilot program we’re hoping to continue, but we wanted to pilot it as part of the festival this year.

The fifth graders are just amazing. Our process has been to ask them some of their favorite poems they wrote, and then which ones do they think they could teach to a younger student and then going through what they learned and trying to organize that. So they’re really making the lesson plan. And then we print up the lesson plan for them to have and they with work with their kindergartener and they’re transcribing for their students too so that they can get through a bit more.

It’s been amazing. They were nervous before the first lesson they were like, “I don’t know, what if they don’t listen to me.” And then they were ecstatic after!

I asked last week after our first lesson: Tell us something you learned after your first day with your kindergartener. The most amazing answers.

One that comes most to my mind is one kid said, “I learned that when you teach someone something, you cannot underestimate them.”

That’s a passion project of mine. I have a background in early literacy, and I was a kindergarten and first grade literacy interventionist for a while and I know that, from a literacy standpoint, we usually don’t catch gaps in literacy until students are tested in like third grade, but the literacy lacks really start around kindergarten and first grade.

I think of poetry as a little backdoor into literacy. There are students who struggle with reading or writing in the way that it’s traditionally taught, but the creative approach can just turn things on their head enough for it to click and create a different relationship with reading and writing and build that confidence. Being able to do that at that super early literacy level is really important to me. And so this Writing Buddy project plays, in a way, to kind of approach that.

Donnie Welch: Yeah, that is incredible. I feel like I could do a whole interview just around that project. I have so many questions and thoughts already.

Caroline Cabrera: It’s been so fun!

Donnie Welch: Alright, to bring this one to close though: What’s the best part about being a Miami poet right now?

Caroline Cabrera: Every other place I lived, the poetry and literature community were super tied to academic institutions and it feels like poetry is very democratized in Miami and it’s alive and vibrant.

Donnie Welch (he.him) is a teaching artist living in Northern Manhattan who has been in the classroom since 2014. His teaching integrates sensory, movement, and rhythm to make the abstractions of poetry and writing more accessible. His workshops function with the belief that: movement helps us understand rhythm, rhythm helps us understand poetry, and poetry helps us understand each other. Along with his education work, Welch is a published poet and children's author represented by Lynnette Novak of The Seymour Agency. When not teaching or writing, he can most likely be found hiking in Inwood Hill Park, the Hudson Valley, or somewhere along the Appalachian Trail.