In April, Bauhan Publishing published Sparks from the Anvil: the Smith College Poetry Interviews, a collection of interviews with superb contemporary poets by writer and teaching artist Christian McEwen. Throughout the year, Teachers & Writers Magazine has been publishing highlights from this impressive book. Here, McEwen and Aracelis Girmay talk about the musical propulsion at the heart of language; about staying emotionally present in a world that too often cherishes the glib; and about the roots of Girmay’s fiercely individual work.

Aracelis Girmay is the author of the poetry collections Teeth and Kingdom Animalia, and the collage-based picture book changing, changing. Girmay has won the GLCA New Writers Award and the Isabella Gardner Award, and was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. She has received grants and fellowships from the Jerome, Cave Canem, and Watson foundations, as well as Civitella Ranieri and the National Endowment for the Arts. Most recently, Girmay’s poetry and essays have been published in Granta, Black Renaissance Noire, and PEN America. This year, she was one of the Whiting Writers’ Award recipients.

Christian McEwen: We spoke together back in 2009, and I’ve been reading over the transcript and noticing again the richness of your heritage. Your mother played the congas and your grandmother did her PhD on salsa lyrics. There was always music around. How did that music influence your writing?

Aracelis Girmay: Music…I’ve been reading Gwendolyn Brooks with my students at Hampshire [College]. It’s a small, sweet, sharp, sharp group. And I’ve been thinking about how, in Brooks’ work, there’s a layer of narrative that you can understand, pushed along by the words and the meanings of the words, and then a kind of sonic narrative that happens underneath, even if you just beat out her beats and her meter, without letting people know what the words are. The kind of “sonic narrative” that happens underneath a poem is something I’ve been really, really interested in.

When I think about the music, part of what I think about is that I don’t speak Tigrigna. That’s one of my dad’s languages. There’s a kind of music in Tigrigna that feels very similar to the sonic narrative in Brooks, when you don’t quite know what the words are meaning, but you hear the pattern of speech.

And so, in some of the poems in Kingdom Animalia and a few in Teeth, there’s an attempt to try to follow what I think of as the Tigrigna music in English. That’s something I want to think of more, especially my own intimidation. How intimidated I can get when it comes to scanning [a poem]! I sometimes worry that my ear is mishearing the accent or stress, though now, more and more, this is less worrisome and more interesting.

CM: Has music helped give you courage in terms of technique, and perhaps also a certain readiness to listen?

AG: I’m struck by that idea of music as giving someone, me, a poet, anyone, courage. Could you say more about what that could mean?

The fact of the drill clanging outside. Or the daffodil, seemingly still in a field. So: what might the drill help me to see about the daffodil? What might the daffodil help me to ask about the giraffe?

CM: I suppose for myself, when I listened to my uncles playing Scottish folk songs, there was a way that music entered the blood and straightened the spine and enlarged the sense of possibility. And did it all in a magnificently non-verbal way.

AG: That’s interesting, really interesting to me. I think there’s a kind of pulse in some of the poems. And I guess I’m thinking literally of the music of them: a kind of litany-like pulsing or engine behind the poem. It can sometimes feel like that, like a motor that is so pulsing that you have to keep digging and investigating further.

[It] makes me think about reading Darwin, and the fact that we’re all somehow related. The fact of our inter-connectedness helps me—how do I say it?—to rethink who I imagine might speak to music. Or what I imagine music might come from. The fact of the drill clanging outside. Or the daffodil, seemingly still in a field. So: what might the drill help me to see about the daffodil? What might the daffodil help me to ask about the giraffe?

And this connects too with the question of silence, the silences I’m loyal to, and why. And then there are the silences that come from imagining that X, whatever X is, doesn’t have language or can’t speak. And the poem’s asking me to think about these things, and helping me to listen more deeply, thoughtfully, whether they’re human words or not.

CM: Kingdom Animalia has a powerful undertow having to do with mortality. As if the fact of death were a lesson you were impressing on yourself over and over again. I think particularly of your lines:

Oh, body, be held now by whom you love.

Whole years will be spent, underneath these impossible stars,

when dirt’s the only animal who will sleep with you

& touch you with

its mouth.

AG: The last time I went back to Eritrea, I spent a lot of time with my grandfather’s brother. When it was time to leave, I remember crossing the tarmac to get to the airplane, and how deep and black that night was—everything just seemed so beautifully, densely black. And every step leaving felt so full of distance, as if each step was like a thousand miles, you know, just getting on the airplane and realizing I probably wouldn’t see him again. He was ninety-six, the last time I saw him, and he has died since.

And my grandmother’s sister, who was a beautiful, beautiful spirit, she also died. That was the last time I saw her. Being in Eritrea itself feels to me very much about trying to remember or see something, some kind of history or family. And also, being aware of my own time-line, my own life line, in relation to it. Moments I’m there are so short and fleeting. And so I think that these poems are very much informed by those deaths.

But they’re also thinking about a relationship to a place, you know. Going back after six years, and the generational changes that can happen in such a short time. Somehow that forces me to be aware of how small I am, we are, and how small a human life is up against the vastness of the universe. Different things happening in the family. That asked me to look as much as I can, to think about how short this time is, and to try to be present in it.

CM: You have these lines in a poem to your grandfather, “Wear a body I can see with my slowest eye,” and I had a question about the issue of pace in your own writing. The need to slow down; to take things in and be fed by what surrounds you. Not always through the verbal channel.

AG: Yes. Alberto Ríos has this poem where he’s writing about dogs running in the distance. He describes the dogs almost like birds—he doesn’t describe their feet. And someone asked him in an interview, “Why that description?” And Ríos said what was important was getting to articulate what he was actually seeing—and when the dogs were running in the distance he couldn’t see their four legs. He was trying to write away from the assumption that because they’re dogs, you imagine they’re going to have four legs. He talked about “slowing down” or “backing up”—not filling in the gaps, but allowing them to be, for the world to be as you see it. Which also feels to me like a rejection of the quick summary, you know: the slow eye.

Much discovery is born out of struggle, the work of playing, experimenting, but also of flailing through the mess of an experiment, whether emotional or conceptual.

CM: When we spoke last, you mentioned your teacher, Mrs. Robinson, who was your English teacher in high school, and you said she was “one of your necessaries.” You felt seen by her. What does it mean to be seen like that? Who else did you feel seen by? And indeed, how do you try to give that kind of seeing to your own students?

AG: I had a ballet teacher who gave free lessons to the kids in Santa Ana, mostly girls. She’d give ballet classes in the basement of this church. The church was called Saint Joseph’s, so it became St. Joseph’s Ballet, and now it’s a kind of institution. Her name was Sister Beth. Those afternoons and sometimes weekend Saturdays of dancing in a room, and not having to use my voice to say what I wanted to say, but getting to dance as my way of being, was so special. I know I felt really seen by her, and also scared and intimidated. I was very shy. But the kind of looking that a dance teacher does, talking about expression and articulation of every part—your hand, or your feet—and the work of practicing again and again…. You know, I might think, My toe is pointed. But then there’d be that little shift she’d help me make in my foot or in my leg, and seeing that that small shift meant everything. And I can see the ways that that connects to poem making. That kind of rigor and dedication and love, and also that excitement for beauty and effort. She was a beautiful, beautiful model. I should think more about that.

Part of what I hope to do with students is to help create a space where the students feel comfortable experimenting, playing, finding, making big messes. And then also struggling: helping to cause the struggle maybe, and also support it, because so much discovery is born out of that, the work of playing, experimenting, but also of flailing through the mess of an experiment, whether emotional or conceptual.

CM: There’s beauty on the other side of the struggle, or there’s order, or however one wants to put it.

There’s such potency in your references to your childhood. It seemed to me that the terror and the beauty and the loss of childhood had been something of a touchstone in your writing. How was it to become fully adult when childhood is still so mesmerizing, so potent?

AG: Sewn into my relationship with childhood, and my memory of being young, which feels very clear and potent to me—sewn into that has been a loss always. I’m very happy to be an adult. And I was very happy in many ways as a child. But one of the themes of childhood for me was feeling as if I’d been born prematurely, not being ready…. I went to boarding school when I was thirteen. I just remember how I clearly didn’t want to go. My mother drove me in a borrowed car, three hours up to school, and the gate was closed. We could have called someone, or figured out how to get in, but neither of us was ready. She said, “OK, I’ll just bring you back tomorrow.” So we drove all the way home, slept, and then the next day left.

I didn’t feel ready the next day either.

There were other instances, like my parents’ divorce. Many instances, where it felt like there was a backward looking, or a desire to stay somewhere just a little longer. So in my relationship to childhood in the poems—there’s a longing and a melancholy there. I feel very joyful and alive in my life now. But alongside that, there’s an understanding of the death of something. Maybe the death of family in the way I knew it. More than longing for youth, it’s a kind of longing for what I understood the family was. That’s there still, now that I’m older, but there’s a different kind of peace. I am thrilled that I get to decide many things, like if I want to move to a place where I can have a garden. These are things I can choose on my own. Which feels like a giant and glorious gift that I don’t take for granted.

CM: One of the things that strikes me in your work, is its tremendous tenderness and delicacy. For example, when you address the goats, “Were you my children once? Do I know your names?” And perhaps because I come from Britain, from an older, and more ironic culture, I wondered whether your work had ever been mistreated because of that open-heartedness, whether you’d ever encountered cynicism or irony or unwelcome, among readers or fellow-writers?

AG: The first thing I think of is giving a reading where I read that poem. And tearing up—more than tearing up…I started crying, which has only happened to me this once ever at a reading—and it was that very part you just read. There was a kind of confusion: “Why did that happen? Why did that move you so?” I felt misunderstood. People think sometimes I’m being funny. Or that I couldn’t possibly have had this moment with the goats. I imagine that the work could be held in many ways, so I don’t necessarily feel heartbroken by somebody not holding it in the way I intended. But I do sometimes feel I have to say strongly, “No, that wasn’t being cute. This is serious to me.” The poem hasn’t done its work enough if the person reading it doesn’t know. But I’ve definitely had to clarify a few times—and I’m sure it’s happened again and again without me being present.

But, that said, I’m in the world and used to being misread or misunderstood quite a lot, and so while sometimes this hurts more than other times, having gone to school at mainly white institutions, with my particular parents and my particular friends, I’ve been trained in this work of having to really fight and struggle to hear my voice through the voices others have imagined for me, and the identities others have imagined were mine.

CM: I wonder if you’d describe a couple of assignments you might give your students?

AG: Most recently, we’ve been reading Maud Martha in my Gwendolyn Brooks class. You can find it in Blacks, but it was published on its own. It’s got these snippets of prose, numbered prose: moments when the protagonist, Maud Martha, will be in the kitchen chopping up the chicken for dinner, and talking about the fact that the chicken had a family once, and maybe the chicken is a kind of person too. Then, later on, you see her struggling through the birth of a child, and her relationship to her mother, and she feels entirely powerless. Things are constantly changing. Maud Martha as a character defies simplification.

So I ask my students to create two short prose pieces in the vein of Gwendolyn Brooks—memoir pieces where they are dealing with an element of their own subject position, be it class, race, or gender, showing how it might look in one piece, and then totally debunking that in the next piece, based on their own life stories.

Because I think we get these ideas about each other, and certainly about ourselves, based on a fixed identify or a fixed subject position, and I want them to really wrestle with that, which Brooks is doing, throughout her work.

Another assignment was to interview someone of their choosing about “home,” and then to transcribe the interview. And from there, to write a poem using only words from that interview, and another poem in which they could use any words, but where they tried to copy the speech patterns of that character, that persona.

Find and give space to the particularities and idiosyncracies of your voice—the way you speak, the music you listen to, your favorite flower—whatever it is. All that is rich, rich gold, and totally miraculous to me.

CM: If you had one piece of advice to give to those young writers, what would you like them to know, that you now know, from the slight advantage of your years?

AG: I think of rocks forming over thousands of years. Human time is different from geological time, but we’ve been forged by so many things, and to think that you or I exist at all totally blows my mind. So how lucky there’s a person writing a poem, and to not ever feel discouraged, even if that poem is misunderstood, to really work to write in the voice or voices that are yours, as opposed to what you think your voice should be. Find and give space to the particularities and idiosyncracies of your voice—the way you speak, the music you listen to, your favorite flower—whatever it is. All that is rich, rich gold, and totally miraculous to me.

—April 9, 2013

Northampton, Massachusetts

Editor’s Note: This interview has been edited and condensed for space considerations and clarity.

In this video from BOA Editions, Girmay reads poems from her book Kingdom Animalia, as well as a poem by Lucille Clifton. And here, in a Cave Canem Poets on Craft discussion, Girmay joins Fady Joudah and Tonya Foster in a wide-ranging talk at The New School that touches on form, content, and the relationship between poems spread across time.

“For Estefani Lora, Third Grade, Who Made Me a Card,” a poem by by Aracelis Girmay.

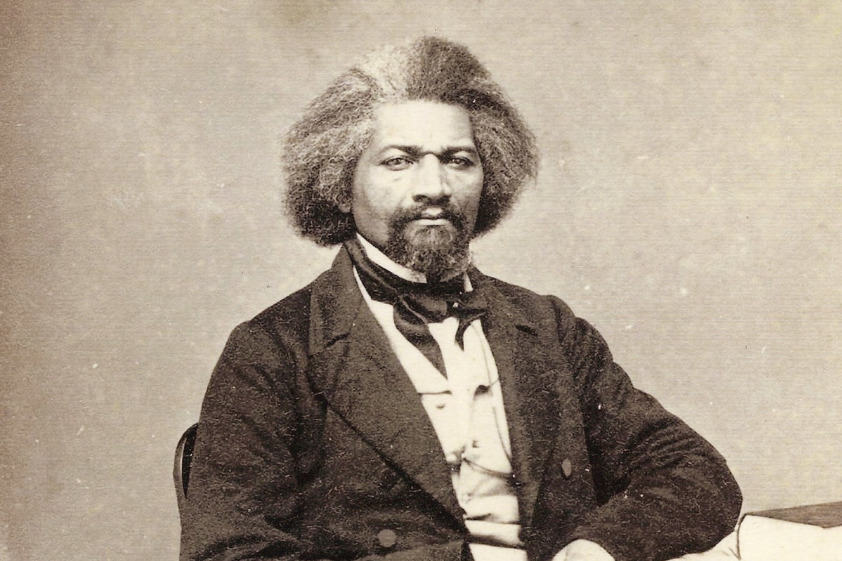

Photo illustration (above); original photo by Jamain.

Christian McEwen is a freelance writer and workshop leader originally from the U.K. She is the author of several books, including World Enough & Time: On Creativity and Slowing Down, now in its eighth printing. She edited Jo’s Girls: Tomboy Tales of High Adventure; Sparks from the Anvil: the Smith College Poetry Interviews; and, with Mark Statman, The Alphabet of the Trees: A Guide to Nature Writing. Christian has enjoyed residencies at Yaddo, MacDowell, Mesa Refuge, and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, and has received a fellowship in playwriting from the Massachusetts Cultural Council. Her new book, In Praise of Listening, will be published in October.