Content warning: this article contains references to suicide, death, and depression. An earlier version of this essay originally appeared in Iron City Magazine.

photo credit for the featured image: Alvin Shim

I. Birdwatching

Late night on Watson Bridge—a span across the Skagit River in Northern Washington—a trumpeter swan flies into a light pole. The pole reverberates with sound. The bird drops onto the highway and stands in the amber light filtering from the large bulb above. No—it reels, dizzy in the vibration of its unplanned encounter with steel. It flaps its huge wings and begins to make sounds that might best be described as cries of terror, as it moves in and out of cars unable to stop their hurtling forward for the sudden and surprising descent of the large white bird.

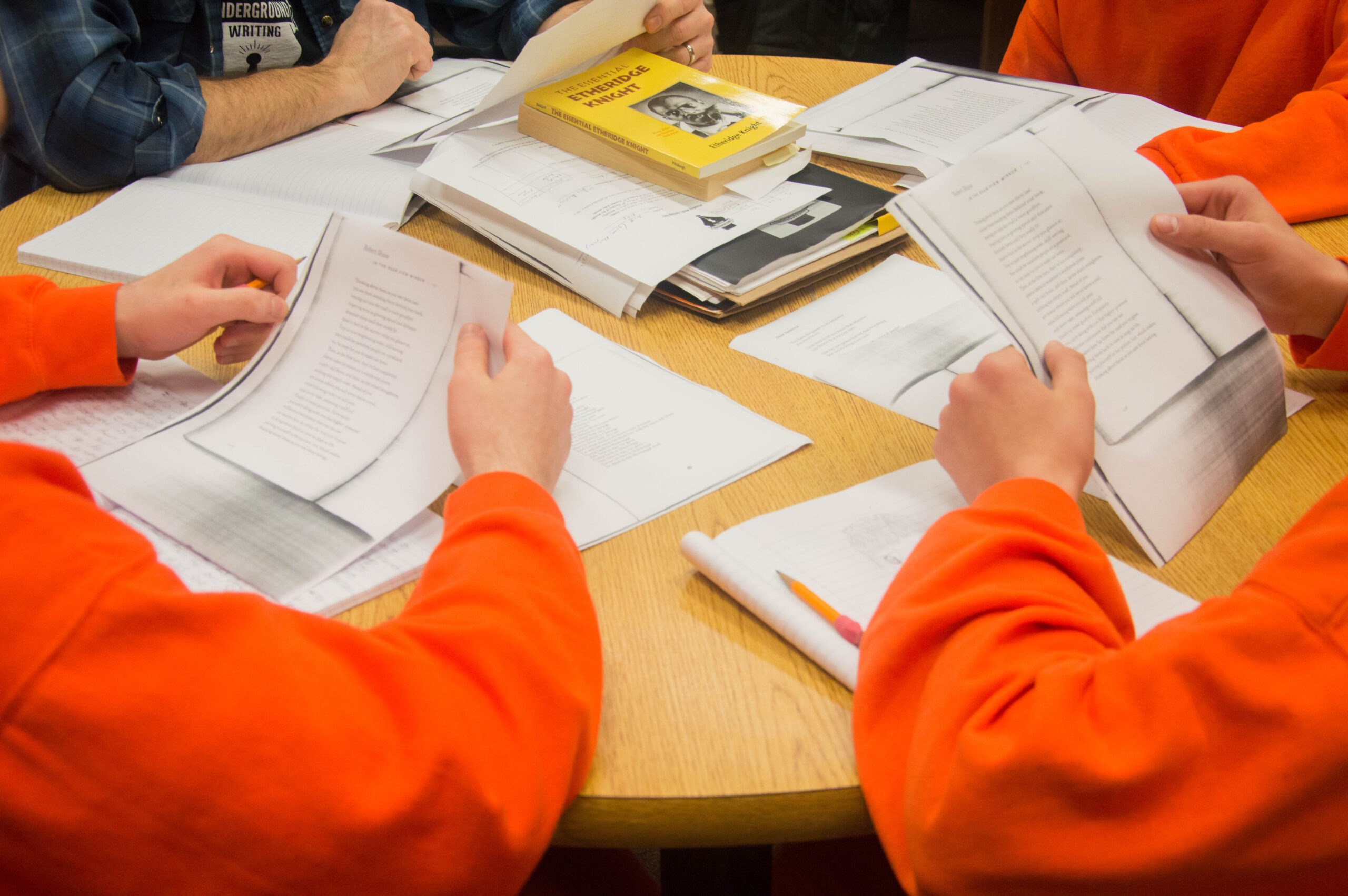

I spend most Wednesday afternoons with youth in orange jumpsuits, holding a yellow No. 2 pencil between my fingers, and leaning over a black-marbled cover notebook. Our county’s incarcerated youth have landed “inside” for various reasons—gang related incidents like drive-by shootings or territorial violence, domestic disputes, harm to

animals, or items involving alcohol and drugs. Unless they write about their past, which they often do, we leave such matters at the door. I shake their hands and welcome them as equals. After introductions we settle into the work at hand—reading literature together and responding to it through discussion and creative writing.

In the early days of facilitating Underground Writing workshops, I began to notice our tendency to bring literature of a darker vein. These included, among others, Dante’s dark wood, Sherman Alexie’s poetry of lament, the non-fiction-fiction of Tim O’Brien, the wars and adventures in Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, the migrant experience of Juan Felipe Herrera, environmental issues in Martha Serpas’ poetry, the tragedy and loss in the poems of Langston Hughes, Jimmy Santiago Baca, Osip Mandlestam, Suji Kwock Kim, and Natalie Diaz, and the darker undercurrents hidden within Robert Frost’s well managed forms.

I caught myself introducing workshops by saying things like, “I know we discuss a lot of darker stuff, but . . .” In time, I realized our students did not share a similar anxiety. They recognized their own stories in this very type of difficult literature.

The truth is that our Underground Writing students, in one way or another, are struggling—the youth in the adult crimes they wake to discover they have committed; our adult students in the physical and mental aftershocks of drug addiction and incarceration; our migrant leaders caught in the intricate web of cultural and familial tensions, in a country seemingly half against them. Such darkness needs to be named, and the dynamic discussions we’ve been having indicate our students intuitively know this.

Late night on Watson Bridge—a span across the Skagit River in Northern Washington—a trumpeter swan flies into a light pole. The pole reverberates with sound. The bird drops onto the highway and stands in the amber light filtering from the large bulb above.

The story that opened this essay was told by a former colleague in an Underground Writing workshop. It stuck with me for some time. I could see it. I could hear it. I wanted to include it in a piece of my own writing. But it wasn’t my story.

In the days that followed, however, something began to evolve.

I recalled what came to mind immediately in the workshop when I heard the story—my father in an auto parts store in Anaheim, California in January of 2000.

Two months before my father’s death—returned home from the hospital after his fifth surgery, and unknowingly a few weeks away from hospice care—he decided to get new seat covers for my mom’s car. He would have nothing to do with anyone telling him anything different. And so, with a body emaciated from years of radiation, cobalt, and chemotherapy in the 70s, and again during the return of his Hodgkin’s Disease in 1999, my father climbed carefully into his golden yellow Volvo 1800 sports car and drove to the local auto parts store. He was nearly a ghost by this point. A perfectionist for his entire life, he had only recently given up shaving due to a lack of energy. He weighed less than a hundred pounds.

I was in Iowa at the time, so I wasn’t there to see him walk gingerly down the aisle, past the various car fluids, on his way to where the seat covers were located. And I didn’t hear the break, as somewhere between the ankle and the knee his tibia simply snapped. My beloved father, a man of dignity and grace unlike I’ve ever known, fell to the floor in agony, surrounded by bottles of motor oil and antifreeze, his brief descent ending as he rolled onto his back, stunned by the white light and the faces above him appearing quickly from all angles of his vision.

As Underground Writing has grown, as we’ve journeyed from the adrenaline burst of new beginnings, articles in the press, and T-Shirts into the settled rhythms of a more established program, one of the facets of what we’re doing that has become increasingly important to me is how our stories overlap, how they connect us.

In January 2016, my beloved mom passed away. It was a grief unlike I had known in years. Part of the intensity was due to the fact that both of my biological parents are now gone. When I shared this news at various times at each of our sites, invariably the room grew quiet. It was as if I could see in slow-motion-time-release the change in the students’ perception of me—white, middle-class teacher to fellow human in a shared journey. We were now strugglers together, and with a common language. We sat together in that moment of silence. Mere seconds, usually, but it often felt as if time expanded so as to contain the gravity of death. And I suspect we each sat in that silence with images and stories flickering through our minds. Stories of blood and lineage and loss and grief, the students unconsciously experiencing a transformation as my narrative merged briefly with theirs then faded into other thoughts based in their lives, their stories.

Late night on Watson Bridge—a span across the Skagit River in Northern Washington—a trumpeter swan flies into a light pole . . .

In the days following my hearing of this tale, I realized that the stories I was hearing in the workshops were no longer easily defined as something other, as “theirs.” And the stories I was sharing from my life were not exclusively “mine.” In fact, my friend’s story was becoming mine, or a part of it, as were the stories shared by our students. In my hearing of them—my taking them in, as it were—they had not been merely received. They had some sort of agency, something that is ongoing. The stories, I believe, are generating connections with stories from my life. They are intertwined with my own and are changing my perception of my past. My stories are also becoming part of others’ stories. Located in the Skagit Valley for a little over a year now, I join them. My life now includes these lives. I am being changed day by day, reeling in the reverberations of such beauty and sorrow.

Weeks later, I recalled a photograph famous in our family for its seeming absurdity. In the foreground my beloved father and his brother are horsing around with their father, my grandfather, on the west-facing, hard brown sands of Manzanita, Oregon, our family’s preferred place of sojourn for four generations. My cousin is building a sandcastle in the background, and behind the small edifice, the Pacific Ocean in all its glory—deep blue, brightly glistening under the evening sun. The lighting is appropriately the golden hour. My father, who is on the left side of the photo, separated by a human-width gap from his father and brother, has his hand held up and out like one side of a cross. Far in the background, but clearly visible, and seeming to rest on my father’s fingertips: a gull, its wings expanding, about to take flight.

II. Gravedigging

In our line of work, my colleagues and I often talk about bringing life into places of death. Whatever a literal resurrection might entail, I’m learning most people need first to discover their entrapment. They also need hope, something that is in scarce supply for many of the students with whom we work. What little remains often needs to be

exhumed.

We use creative writing as a shovel.

It’s hard work, but the willingness to dig is quickly evidenced in the discussions that follow our group reading of a text. And the soil, prepared by the literature, is pliant. By the time the writing prompts are finished, students—through some grace moving in language itself—have often dug down deep enough into the self to reach a grave.

Spaces like these are shelters for decay, narratives of darkness. I hear such stories on a weekly basis . . . The young man who confesses to me he’s locked up for killing his grandma’s dog and doesn’t know why he did it, who then proceeds to tell me of his long history of physical abuse at the hands of an angry father; the man in his twenties I’m asked to speak with on the phone in the glass-protected booth, who is missing an arm he himself sawed off, who has swastikas below his eyes and “perdition” written backwards on his forehead so he can read it in the mirror, who tells me he’s from Manson’s farm; the look on the guard’s face the other night when I asked if any pastoral care had been given to the Cascade Mall shooter, who is currently being held in Skagit County Jail; the young man I counsel who tells me he’s having flashbacks of standing over a rival gang member he’s unwittingly stabbed six times in self-defense, listening to him beg for mercy.

There are other movements in the darkness, too.

We’re privileged to see some of our students on a regular basis and build long-term rapport. It’s satisfying to see the maturing work they produce. Many of our students, however, we see only once, maybe twice, for an hour or two at most. These are the students I wonder about. Will their notebooks ever get used for creative writing again? Will the impact of encountering literature in a given session spark something, anything? Will they contact us on the “outs”? Will they remember writing is a gift and a tool for life? I continue to hope. I continue to believe that literature read together in a hospitable atmosphere, paired with writing prompts connected to both the readings and the students’ lives, begins something beyond what we can quantify. Words matter. Literally. They take shape, and form a space in which things can grow.

Leaving the workshop with a notebook full of words and photocopies of good literature is not our only goal, of course. We’re seeking both inspiration and transformation. This may take the form of a participant’s continuing to pursue the craft of writing and reading in a more purposeful manner. It may simply mean they read more. Or it may mean they

discover writing as a tool to help process a world that usually leaves them confused, angry, and sad. Whatever the case, we endeavor to resuscitate and nurture hope, something tangible that can be built upon, furthered to the point that an imagination of a different future begins to arc toward what they might become. It is across this bridge of the imagination, as it were, that the participants can begin the long journey towards embodying a different future.

I’ve seen writing work this way for two of the students who participated in our program’s initial week of workshops.

R. is from another state, but when I met him he was being detained on various charges in our local area. Although he was noticeably quiet, I often caught him grinning at certain things read aloud or said in our workshops. There was a light on. I liked him immediately.

A month or two after Underground Writing’s debut, our workshop group was discussing the letters of James Baldwin in The Fire Next Time. “Letters can be literature,” we told the youth. “Let’s try it, too.” For our writing prompt, we asked them to write a letter to someone. When it was open-share time, R. decided to read. “I call this one ‘Dear System’,” he began.

Dear System,

Ever since I was born you’ve been there. You were there when my biological mom would relapse and let my sister and I run around free. You were there again as I began to realize how to work on my own and take care of my mom and little sister. You were there when my biological dad went into a rage and hit someone. You were there when my mom used up her last chance. You took me and my little sister from her. You weren’t there when I passed from family member to family member. You were there to give me a new family. You were the one who put both my parents in jail. You put my biological dad in prison. Now you are here again, but this time just for me. You are here putting me in JRA for the same reason my biological dad’s locked up. You have brought me nothing but pain in the 14 years I’ve known you. You have torn apart my family time and time again only to put me in a new one where I’ve done nothing but disappoint or make people angry. So, System, before I finish this letter, I just want you to know I will never forgive you.

— R.

The room was silent. Not only because we’d just heard a sort of foundational text that solidified we were on to something important, but also because R.’s writing was inarguably powerful. In five minutes, his emotions had been honed into something concise that moved beyond mere self-expression. He’d interacted with literature in a dialogic manner, and by the look on his face, something transformative had happened to him during the process.

R.’s out of state now, so we stay in touch these days via letters and the phone. During the course of our last phone conversation, he told me he’s working on a section of a long autobiography project, as well as completing a set of song lyrics. His letters, too, bear witness to the continuing impact of writing . . .

I’m happy that “Dear System” is helping people. That’s a side of my writing that I never considered. I am still writing. So far I have gone through three notebooks. . . I miss going to Underground Writing sessions. I liked it there, I always felt welcomed.

I’ve also seen it in J.—a native to our county, held inside for a record number of months, due to the serious nature of the charges against him. J.’s interest in writing has had extremely tangible benefits. In our workshops he was always eager to share his work.

Thinking

So I’m in deep depression now

There’s nothing I can do about it

I’ve been sleeping all day

I get real tired when I’m this way.

I start thinking and thinking

And my mind goes crazy.

I get the same thought

Over and over—

What would things be like if

I ended my life today?

I stare, and I stare

I think everyone

Who loves me hates me,

Who wouldn’t care

If I just disappeared one day

I think and I think—

Wouldn’t it be better if it all

Just went away.

J. is determined to survive. Likeable from the start, he’s a person I’ve come to appreciate for his strong desire for change and restoration. In the fifteen months I’ve known him, he’s taken to writing as if it were an iron lung. His first letter to me implied it might, in fact, be something of the sort.

As you know, I missed creative writing. I was really bummed out because that’s my favorite programming that I look forward to all week. I’m a ‘security risk’. I’m really stressed out and just going crazy. I’ve never had such severe, strong, and sudden emotions.

Near the end of his stay, we began meeting once a week. I met with him as a teacher or a chaplain, determined by his need on any given day. By the time he was finally sentenced and sent to a juvenile prison, we’d also written seven letters back and forth.

So I made it to [prison]! I was in Shelton for about 3 hours then they took me. I’ve been here almost 24 hours. I’m not sure what to say about this place other than it’s definitely a prison…I found a small section for poetry in the library, but they have like 80% Shakespeare and really old stuff . . . I’ve been writing a ton but most of it is private stuff or my new book, ‘To My Love’. I’m really excited to hear what you think about my prologue. My mom is sending all of my writing from the outs and Juvie. It is so much that she had to put it in a package in the post office.

When I look back over the past fourteen months, writing is the thread that is so apparently woven through J.’s future progress and restoration. More so, what I believe propels J. is what to one degree or another propels all writers and poets—he has encountered the self through writing, and, in that process, imagination, mystery, and hope.

Our correspondence has notably increased in the six months since his transfer, most of it being driven by J.’s own desire to continue learning the craft of writing. He is an exemplar of our program’s hoped-for impact. In 41 letters and counting, we’ve edited and re-edited draft after draft of various poems and short stories. We’ve shared a bit of our own stories. And we’ve also been working on a co-submission to a literary journal, an item that has facilitated further momentum toward change for J.

I’ve been inspired once again to be a part of Underground Writing or a similar group/organization when I get out. This program changes lives. I am a prime example. I now have something to work towards, to strive for. I have something I want on the outs.

The weekend after Thanksgiving, I was able to visit J. in another part of our state. Amidst a room full of families and loved ones visiting their sons, their boyfriends, their dads, I sat with J. for one and a half hours. We talked about life in his new surroundings, as well as his hopes for the future. He’s feeling settled in his living unit, and his medications have finally stabilized. There have been challenging and good reconnections with his family. He’s just turned eighteen and is registering to vote. He’s applying to take classes through a local community college, and is determined to use what little money he has left to help his mom in paying for his tuition. In my estimation, the hope for change has transformed into actual and definable progress.

“You’re doing great,” I say to J. as we shake hands. “Really great. So glad to see it.” I tell him I’ll return in a month or two.

He smiles. “You’re going to send out our submission next week—right?”

Reading Flannery O’Connor recently, I was reminded of a story received from the ancient tradition of the desert fathers and mothers. There was a hermit living in the region of Scetis who had become seriously ill. His fellow monks, upon visiting him one day, discovered that he had died, and began to prepare his body for burial. All of sudden, he awoke, opened his eyes, and began laughing. After recovering from their surprise, the brothers asked him what he was laughing about. He told them he was laughing because they feared death, because they were not ready for it, and, finally, because he was passing from labor into his rest. With this he rolled over and died.

Death for such monastics was a way of life. A way to life. And reportedly, some monks in ages past did indeed sleep in their coffins. When presented with this bit of history, my son tells me the monks were probably hiding from something. I asked some of the youth in Underground Writing what they thought.

A: “To get away from everything for a while.”

O: “Maybe it was part of their praying.”

L: “Because they’re getting ready to die.”

In some sense, all of these answers are correct. Monks have always been consciously mindful of death. Sleeping in coffins was simply a more obvious way of facilitating this. It was likely their way of hiding from the very act of hiding—a way to actively seek an encounter with reality. Whatever the people in surrounding communities may have thought of the practice, to say nothing of the explanation, it was not a sorrowful thing. Nor did it lead to depression. In fact, a monk’s literal descent into his future place of death allowed him to more fully engage life. It became a conduit for joy, allowing a monk to wake to the freeing realization of his mortality.

In the literature we discuss with youth and adults, in the writing we do as a generative response, we more often than not enter into the darkness of our lives. These unlit places may be as simple as a general lack of clarity or as complex as navigating the extrication of oneself from the clutches of drug addiction, gang involvement, or repeating cycles of shame and perceived failure. Whatever a student’s degree of darkness, by directly descending into it—through the profound mystery of reading/writing—something begins to happen. They begin to voice the ineffable. Words become sentences become beauty. In less than an hour, it’s surprising to witness the claustrophobic encasement of each student’s life opening up a bit. So begins a fissure. And through such gaps daylight begins to filter in.

Matt Malyon is the executive director of Underground Writing, as well as a jail and juvenile detention chaplain. He is the author of the poetry chapbook, During the Flood. His poetry has received a Pushcart Prize nomination and has been featured in various journals, including the University of Iowa’s 100 Words, Rock & Sling, Measure, and The Stanza Project. He serves as a mentor in the PEN Prison Writing Program, and recently founded the One Year Writing in the Margins initiative.