This article is part of a series in Teachers & Writers Magazine on working with immigrant and refugee writers. Related content includes One Day You Will Be One of the Happier: The Voices and Poetry of Teen Immigrants, Poems Without Borders: Writing to Bear Witness, Creating a Map of the World: Working with Somali Immigrants in the Writing Classroom, Better Advocacy for Undocumented Students, and our interview with 2018 National Teacher of the Year Mandy Manning.

“America” by Claude McKay

In November 2018, after nearly two semesters of leading a poetry club at International High School at Union Square in New York City, I was reminded of two things: 1) I love teaching teens who are recent immigrants, and 2) I need more poems in my arsenal. I felt almost desperate for poems that would be suitable for the reading and comprehension levels of my English language learners, but would also be appropriate for their level of intellectual and emotional maturity. My prayers were answered (at least for that week) when I heard Kwame Alexander recite Claude McKay’s poem “America” on NPR, and ask listeners to write poems that express what they’re thankful for about America.

Granted, it was almost Thanksgiving, but the task felt like a tall order given the ongoing, seemingly ever-widening divisions in our country. Certainly I was thankful that the midterm elections were over, but in one month alone there had been a shooting in a yoga studio, a shooting in a hospital, and a shooting at a mall. Thankful for America? Alexander explained, however, that “sometimes in the midst of all the news and daily woes, we forget about the wonder.” Sure, I thought, okay. In his poem “America,” McKay, who was himself an immigrant, hailing from Jamaica, was able to acknowledge the wonder he saw in America while not hiding the rancor he also felt toward his new home.

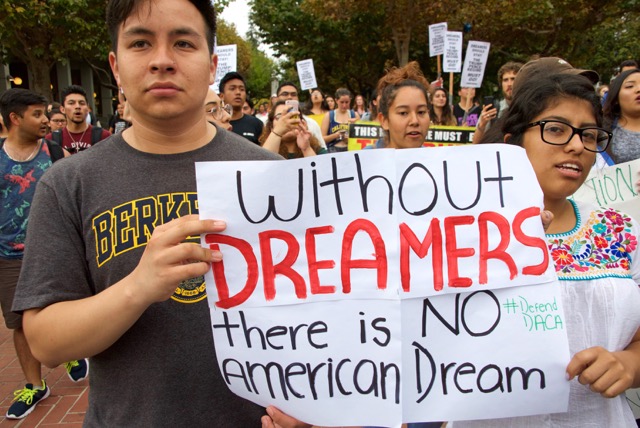

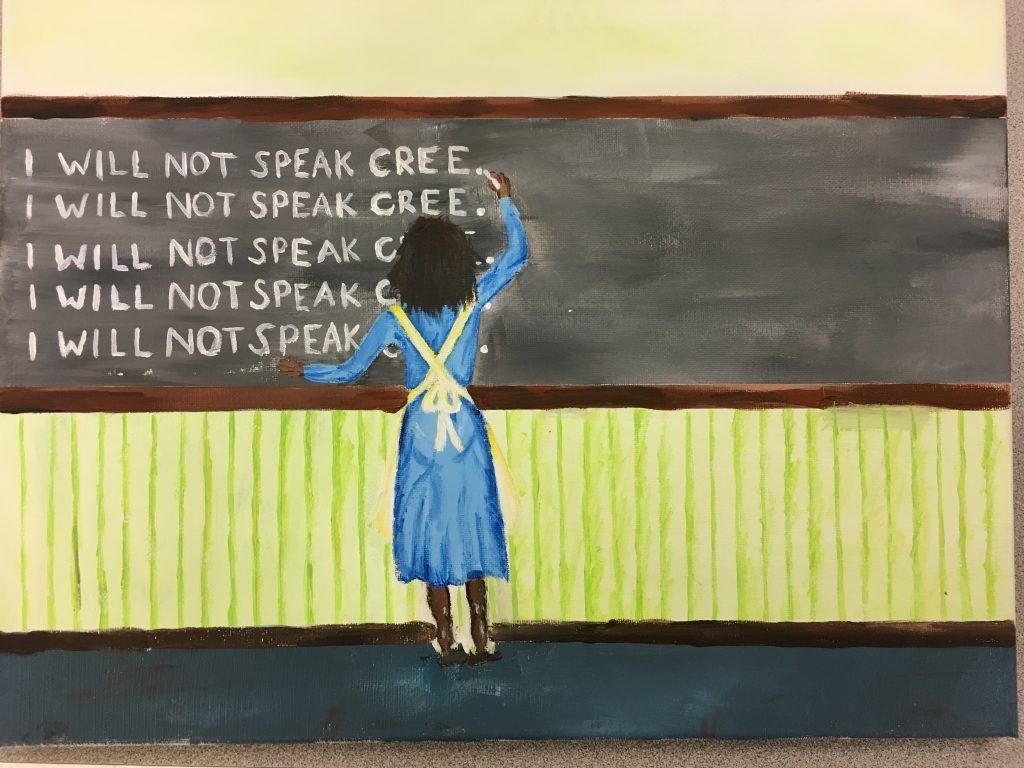

I have often been disturbed by how quickly so many Americans claim that the United States is The Best Country on Earth as they speak of all its freedoms, while there so many here experiencing the harsh realities of our country’s extreme and myriad inequalities. Immigrants in particular often feel pressure to show only gratitude toward their adopted homeland, to accede that yes, America is The Best Ever.

While the vocabulary in McKay’s “America” is not easy to decipher, my students were easily able to pick up on the contradictions in McKay’s poem, with words like “love” and “hell” found in the very same line. We had already discussed metaphors, so it was not difficult for the poetry club members to grasp the stirring imagery in the poem’s opening lines, recognizing the inherent contradiction in the metaphor “bread of bitterness.”

We delved a bit into contradictions—what it’s like to hold two ideas or two feelings at once. For example, how it’s possible to feel both infuriated with a family member and to love him or her at the same time; to crave the attention of a person as we avoid him or her. At first I encouraged my students to write their poems as Alexander had suggested on his radio segment—to write a simple list poem of gratitude, with each line starting with the words “Because America”. “Because America…is complicated,” he and the radio host, Rachel Martin, collaborated, “Because America…is open.”

This setup didn’t work as well as I’d hoped to encourage students to get down their ambivalent feelings about America. Because my student writers are English language learners of varying levels, I scaffolded the lesson by writing a class brainstorm of the pros and cons of living in America. After we drummed up some ideas together, I invited students to write their own lists of the pros and cons on their individual papers, reminding them to be as specific as possible. Some students went one step further and compared the various aspects of America to their countries of origin. With prewriting complete, students then made poems of their contradictory feelings. In most cases, students used one item from the “pro” side of their T-chart along with one item from their “con” side to create a couplet, and then went from there as they added details to each line of each couplet. I encouraged the higher-performing students to write a poem with at least five couplets. But not all students did that, and frankly, I liked that most took the activity in whatever direction they wanted. It made for more variety in their work, and it reflected a more honest appraisal of life in America—a life that is impossible to boil down to either good or bad.

“American Dream”

by Xiao Na Guo, Grade 11

Because America is the land of opportunity

But economic inequality is growing significantly

Although the government provides health care for everyone

There are homeless people in the streets, in the subways and everywhere

Although education is provided for all

Some people can’t afford college

Although New York City is great

Its subway is old and dirty

Its housing is dead expensive

America is rooted with racism

People don’t love each other here

People are against each other because of their skin color

Some fight for the American dream and others just want to stop them

It’s America

Overall

I love this competitive place

America

by Uriel Solis, Grade 11

America gives me freedom, my teacher told me,

but I am illegal and so I cannot see it.

America told me she has money,

but she forgot to tell me that I have to work.

America called my parents and then

I came.

America has so much food that

I don’t even know what to eat.

America told me to go to school

but I’m too lazy to wake up

when she is too cold.

“breaking away to the u.s.” by José B. González

In further pursuit of poems that would be fitting for both my students’ reading and comprehension levels, as well as their maturity, I came upon José B. González’s wonderful poem, “breaking away to the u.s.” In the poem, González, who immigrated to the U.S. when he was eight, describes his final day in El Salvador, “a day so perfect that / this morning’s awakening bombs / are overtaken by a woman’s wind chimes / of ‘tamales, tamales.’”

It can be disturbing to read the phrase “awakening bombs” for any student, but luckily for my poetry club at International High School, one of the club’s most ardent members is from El Salvador, and was eager to provide the needed context—that El Salvador has a long history of civil unrest. While the Salvadoran Civil War officially ended in 1992, the country’s postwar years have seen a growing number of “Maras” or gangs, leading to a mass exodus of Salvadorans, of whom my student, Uriel, is one.

Uriel was also able to shed light on some other aspects of the poem for us, telling us what a Maquilishuat tree, the national tree of El Salvador, is, and how beautiful its pink blooms are. Uriel spoke wistfully of his former home, as did all of the other students, a few of whom also come from countries where there is grave conflict. The details in González’s poem had done that to them. They made the students think of the last day they had had been in their former countries — and not only the conflicts they left behind, but the simple beauty of their countries, too. But González’s poem goes one step further. It places the conflict alongside the beauty; in González’s poem, the “rotten bullet seeds / are overtaken in flowering weeds.”

While some of my students—especially those from Yemen—occasionally feel the need to write about the killing and death they experienced, perhaps in an attempt to move past it, in general I find that very few of the students want to write about the traumas they left behind. And understandably so.

What’s great about using “breaking away to the u.s.” as a model poem, is that one can also simply ask students to write down all of the details they can remember of their final day in their country of origin. I have spent what feels like the lion’s share of my time with the poetry club at International High School telling members to rely on sensory details in their poems—what they saw, heard, smelled, tasted or touched—rather than simply narrating their experience. We discussed how well González does this in “breaking away to the u.s.” The speaker doesn’t tell the reader that he feels scared or that he misses his country despite its violence, but the poem’s details definitely show us. Students understand the difference.

Fanny, who’s originally from Ecuador, most certainly took the wistful tone of González’s poem to heart when writing her own poem about her final day before coming to the U.S.

“I Would Be Able to Be Okay”

by Fanny Aucacama

Finally

It was the morning of Julio 11

I wake up scared and I saw my maleta

in front of my bed, that was a signal

that I had to prepare to go to the airport

I looked around my room and it seems

like there was a shadow

I was peparando my bag and

I saw my grandmother in front of me

crying. I was trying to be brave and

I told her that everything is going to

be okay.

I was packing and carrying my bags

and I saw one of my cousins, he was

looking at me, suddenly I felt

strange. In my mind I was saying this

is not real this is a dream

but it wasn’t.

It was around 9 o’clock in the morning

my aunt told me I had to eat

my breakfast

on my way to the airport I saw some of

my family I couldn’t say any words I was just

sitting in the taxi. I saw my two little dogs and

they made me smile.

About the Author:

Sarah Dohrmann is a Brooklyn-based writer. Her work has appeared in Harper’s Magazine, Tin House, The Iowa Review, New York, Condé Nast Traveler, Bustle, Joyland, and the New York Observer, among others. She has received writing awards from Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, Fulbright, the New York Foundation for the Arts, the Jerome Foundation, the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, and the Aspen Writers’ Foundation, among others. Sarah has been a writer-in-residence with Teachers & Writers Collaborative since 2001. She also teaches writing in Liberal Studies at New York University and at the Writing Institute at Sarah Lawrence College.

Photo: Sheila Fitzgerakd

Sarah Dohrmann is a Brooklyn-based writer of literary nonfiction whose work has appeared in Harper’s Magazine, Tin House Magazine, The Iowa Review, and New York, among others. She began teaching in the schools with T&W in 2001 and currently teaches at New York University; she also independently leads a personal nonfiction writing workshop called Diving Into the Wreck. After earning her MSW in June 2023, Sarah serves as a clinical social worker in the Domestic Violence Aftercare Program at University Settlement in New York City's Lower East Side.