FROM THE ARCHIVES: This article was originally published in Teachers & Writers Magazine January-February 1996 – Vol. 27, No. 3.

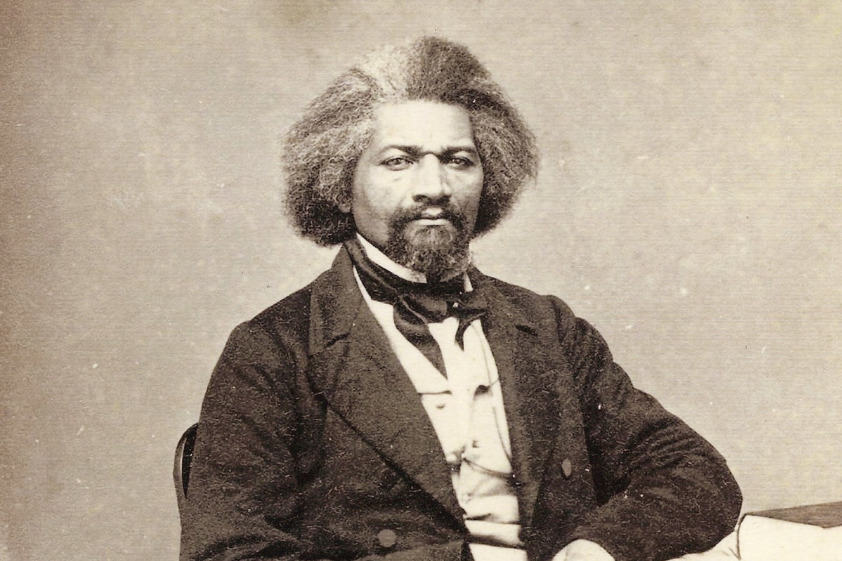

I have found that one of the most successful pieces of literature for motivating students to read and write is the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. It opens up so many issues of adolescence, such as self-esteem, identity, rebellion against unjust authority and laws, individual dignity, and control over one’s life and working conditions. Add to this a poetic writing style, and one readily understands why students become absorbed in the Narrative.

Farragut Career Academy, where I have taught since 1965, is located in the inner city on Chicago’s Southwest side. Our students are Hispanic (eighty-five percent) and African-American (fifteen per cent). A large portion of them are on public aid and below grade level. Much of their energy is expended in a day-to-day struggle against gang-bangers and other social ills.

I use the Narrative in my American history and ethnic studies courses. Students in these classes are upperclassmen.

What makes it easier for me to teach the Narrative is my admiration for Douglass. Indeed, he’s one of my personal heroes. Besides the Narrative, I’ve read the two later autobiographies, My Bondage and My Freedom and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, as well as other materials, such as the recent biography by William McFeely. So in teaching the Narrative, I can give my classes a rich background on the historical period and on the man.

Many students are not aware of Douglass; others may have only a vague recollection of hearing about him in history class. Before we begin reading the book, I give some background information on his period and on slavery. In addition, I show a documentary movie—unfortunately out of print—on the life of Douglass entitled House on Cedar Hill. (You might substitute the PBS video When the Lion Wrote History.)

I should say, in all honesty, that students do struggle with the book, due to low reading levels, lack of experience in reading and discussing literature, and problems with English as a second language. These difficulties arise in the writing assignments as well. One way of dealing with these problems is to have the students make a little book of notes for each chapter. They make a title page and label the subsequent pages by chapter. Each chapter page contains important points for that chapter as it’s summarized in class discussion.

Also, I go through most of the chapters with the class, reading certain excerpts orally, asking questions, and making connections with the current situation in our society. There will be two or three key chapters that students will read very carefully, using guide questions for class discussion. Bilingual help is given by some of my students who act as tutors for those who are limited in English proficiency.

Until they read the Narrative, most of my students are unaware of how inhumane slavery was. Some become visibly angry about what they learn. I attempt to channel that anger into constructive actions that they can take for themselves and others, using Douglass as their role model. For instance, I show them that they can have better control of their destiny by empowering themselves with better literacy skills.

Moreover, I point out that Douglass exemplified self-respect, strong moral character, aggressiveness, courage, intelligence, and a deep sense of racial pride and responsibility. For Douglass, struggle was more important than compromise, dedication to the freedom of his people more important than his own safety. He felt responsible for secretly educating his fellow slaves, and for helping them escape from their bondage. The message to students: fight against prejudice using reason, using literacy skills. Don’t enslave yourselves with voluntary ignorance, drugs, gangs, or early teenage pregnancy. Help others as you have been helped.

While reading the Narrative, the students keep journals. Not surprisingly, I get many moving entries inspired by certain sections of the book. In the early part of the Narrative, Douglass writes about the significance of the spirituals sung in the fields by the slaves. One class heard recordings of some of these “sorrow songs” and one of our music teachers gave a special presentation showing the link between spirituals, blues, and gospel music. One Hispanic student who’s not afraid to cross racial boundaries has some close African-American friends. One of these friends invited him to attend a church service. For the young Hispanic it was a beautiful spiritual revelation. He wrote, “Believe me there’s nothing like a black church service! It cannot be copied! The preacher preaches up a storm and gets reactions from the congregation. Then there would be the singing of the church choir. That church would rock. One could feel welling up within oneself a sense of love—a sense of faith—a sense of unity—a sense of hope.”

Douglass’ two-hour fight with the “slave breaker” Edward Covey elicited another student’s comment: “I envy Douglass’ courage in fighting Edward Covey and to escape his master. Never have I heard a story like this—the way he conquered his problems.”

In the first chapter, Douglass relates how he hardly knew his mother, and that when she died, it was as if a stranger died. That led to this poignant journal entry: “I’m really sorry about Douglass’ family that he lost or never saw. I know how Douglass feels because I never saw my mother because we got separated just like Douglass did.”

What we have here are prime examples of how a powerful poetic writing style helped these Hispanic students identify with an intelligent, courageous black slave and, thereby, narrowed some cultural and ethnic gaps.

Another writing activity I have the class do involves elements of a “twilight zone” experience. Students are to pretend it’s 1845 and to write a letter to Douglass indicating their reactions to and feelings about his Narrative. But within the letter they will crisscross between the past and present.

The format for the letter is as follows. In the first paragraph they introduce themselves and write about three scenes in his book that horrified them. The second paragraph contains examples of courage and intelligence shown by Douglass. In the third paragraph, students request advice from Douglass and describe the racial tensions at Farragut. Then students suggest, in the fourth paragraph, two things they would do to reduce these problems and, in a final paragraph, they may say whatever they wish.

Students have no problem in straddling the timelines and usually enjoy doing the assignment. However, for those who wish an alternative assignment, I offer the essay topic: “If Frederick Douglass were alive today, what message would he bring to Farragut Career Academy students about improving racial relations?”

Another activity involves the use of large white posterboards. Small groups of students complete a posterboard book report on the Narrative by doing what I call story mapping. In the middle of the board goes the title, author, and publisher.

On the left and right sides of each board there are sections for a character map of one of the protagonists, new vocabulary words, setting, plot, a symbol that students invent that represents the story, and three completed sentences about the book. At the bottom of the board, the theme or message is stated and explained. Students can be as creative as possible in putting this together, including the use of drawings and pictures. Students love working in groups and doing this kind of writing assignment. In past years, I’ve gotten some extremely well-done posterboard story maps that have been displayed in the classroom as well as schoolwide.

Finally, since the students have been writing Douglass’ story, I ask them to write their own stories, which students really like to do once they get over their initial reluctance or perception that their lives are dull. Realistically, how often does any authority figure ask them to write about their own souls and to make themselves the topic of a written school assignment? It gives students a sense of personal importance, the type of environment discussed in the Narrative when Douglass relates how he secretly learned to read and write, and how that changed him from a non-thinking slave to a thinking man who became resurrected, if you will. When the students complete their autobiographies and see them displayed in the room, it gives a needed boost to their vulnerable self-images.

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is an invaluable and powerful autobiography that not only inspires students to write, but also teaches them that people can transcend group distinctions, whether racial, ethnic, class, or gender. It also shows them the link between literacy and personal empowerment, that they, too, can overcome personal obstacles and become the masters of their own fates.

More Resources:

The T&W Guide to Frederick Douglass by Wesley Brown

Charles Kuner has taught at Farragut Career Academy in Chicago since 1965 and has worked extensively with curriculum development in the social studies. He has an M.A.T. in U.S. history and an M.A. in urban sociology.

One response to “Using Douglass Narrative to Inspire Student Writing”

Excellent piece. I am honored to have my essay, ” Going To See Frederick Douglass”, in the same T & W Guide!