Social justice was at the roots of the formation of Teachers & Writers Collaborative (T&W) when, in 1967, a group of writers and educators met to reimagine the teaching of writing in schools. They crafted a manifesto for teaching writing which emphasized that “children should be allowed to invent the language by which they manage their world” and be “encouraged to make uninhibited and imaginative use of their own verbal experience.”1 This emphasis on allowing children agency in the use of language and a safe space in which to create authentically remains central to the work of T&W today.

Children in New York City face increased wealth disparity, poverty (one in 10 NYC public school students was homeless in 2020-2021), and unequal access to the arts; mental health and learning challenges exacerbated by remote learning at the height of the pandemic; and a world increasingly overshadowed by news of violent crimes, racial and political unrest, and injustice.2 T&W believes that when students are given the freedom, tools, and encouragement to express themselves through imaginative writing, they become empowered in a way that extends far beyond the classroom.

Members of the T&W family recently contributed reflections on our work to the forthcoming German anthology Literacy und soziale Gerechtigkeit: Theorie – Empirie – Praktiken (Literacy and Social Justice: Theory – Empiricism – Practices) edited by A. Bramberger & S. Seichter. With gratitude to the publisher, Beltz Juventa, we are sharing these reflections in Teachers & Writers Magazine. This month, teaching artist Javan Howard shares about processing what it means to live and learn with his students through poetry.

—Asari Beale, Executive Director

I fell in love with language on the roof of my project apartment building in the Bronx. It was there, looking out on the world with the rigid warmth of gravel under my feet, that I read and wrote my first poem. It wasn’t a good poem, but it was my poem. Something I didn’t think I could ever create.

In 3rd grade, a teacher told me, after I’d failed an art assignment, “You’ll never be an artist.” I held on to that sentence for a long time and didn’t want to do anything creative. I never read a poem in school and didn’t know any poets in my life. I didn’t know being a poet was possible. Still, I was drawn to the rhythm of words. The hip hop in my soul always searched for metaphors to express myself when the words couldn’t string themselves together well enough. I was the quietest one in my family and amongst my friends. It wasn’t because I didn’t have anything to say. It was because I didn’t know how to say it. Wherever I went, I was deep in thought and my imagination ran wild, but words escaped me. I kept notebooks on notebooks to write things down before I could forget them. But I didn’t know what I was doing then. I didn’t think of myself as a writer.

It was then, in the seventh grade, that I knew I wanted to work with language, to be with language. I grew up in an environment where language often worked against us or got us in trouble. In the right hands language could be a blessing or a weapon. We knew language was more than words. It was also a look, a feeling. It was a memory, or unwavering pain held in the body, or a laugh that captured the room like dense sunlight through an afternoon window. It was a collection of experiences that your friends could translate in an instant to know when things are all good or when something doesn’t sit right. Language is all around us, and it exists in every way. Poetry is our grandmother’s look, poetry is a handshake with your best friend, poetry is the song you and all your friends know the moves to. That’s what poetry is; anything and everything you want it to be. It’s a collective matrix of experiences that help us be or learn something about ourselves.

Who am I to deny my students cathartic justice through their writing? . . . We come to words in order to make things live, to give them new life.

The way I came into poetry is the same way I teach it. I give space for it to be anything my students want it to be. This summer my students are obsessed with death. I think this is normal and many can certainly understand. We all carry a certain heaviness with us coming out of a multi-year pandemic and the various social upheavals that have literally and metaphorically taken the breath away from many. As a poet, I often come into poetry to process my own grief. Who am I to deny my students that same cathartic justice through their writing? We all have a relationship to death. We come to words in order to make things live, to give them new life.

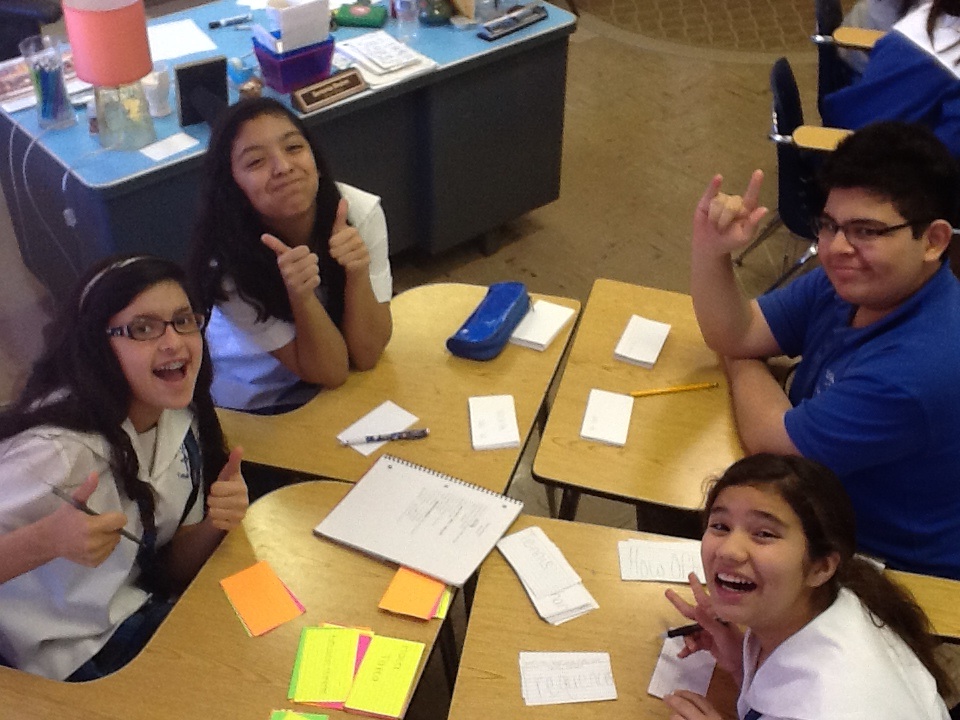

Sometimes we are just searching for permission to write about the things that we are already thinking about. When I told my students how Toi Derricotte has a collection of poems, For Telly the Fish, on her pet that died, they fell out. They didn’t think it was possible to write a poem about a dead fish. They wanted to hear more. So we read “Another poem for a small grieving for my fish Telly.”3 They were enamored by it all: the loss, the innocence, the pain, the guilt, and the love. My students wanted to embrace death from a place of joy. We shared story after story of all our experiences owning pets. Through the art of storytelling, we grew closer and closer, and then we wrote. This poem was written by one of my students who was very excited to share his poem “about my fish and how they all died” at our summer camp student festival performance.

One big fish, three small

— Dean M, 2022 Usdan Summer Camp For The Arts

Some short, some tall

In your tank, you swim all day

But not enough space to swim and play

In the dark, an empty room

You wait until you meet your doom

Like being trapped in a giant cup

Until you just go belly up

The audience loved his piece, sung his praises, and could only talk about all the fish they previously owned. His poem did exactly what poetry should do—spark a conversation. We should be encouraged to use the broken pieces of ourselves to create a new and meaningful world. We used Toi Derricotte as inspiration to write about hard topics from a place of joy, creating haikus for grandparents that were lost and odes to a plethora of our dead fish with no names.

Sometimes the best part of the poem isn’t the poem itself. It’s the conversation that it brings, the memories, responses, and smiles it elicits. One poem can mean many things to one person. And it can mean the same thing to many people. When teaching, my goal isn’t for my students to understand the poem, but rather to experience the poem. So that’s always my approach when teaching poetry; creating an experience, building a relationship with the words. Inspired by the poem of the same name by Nikki Giovanni, I treat every workshop like “A Journey.” That is often the first poem I share with my students to let them know I am merely a guide that anchors our relationship towards being through poetic inquiry.

In my teaching, I am guided by several questions for the class to simultaneously process what it means to live and learn through poetry. I question: How can I start a conversation? How do I create access to language? Those questions are the moving carts for students to find their place in. How do we access forms of expressions? How do we process [ourselves or really any literary theme] through the art of critical imagination? These questions help put the text into context and establish our relationship to the text and the world. Everything intentional or existential starts with a question. Poetry is that place to question. Poetry is that place for cultural engagement, understanding, and where we can simply bear witness to the throws of humanity.

There is a certain kind of grace that has to happen for a poem to exist in this world. For a poem to build understanding and become a bridge to something or someone, there has to be a point of connection. For teaching artists, who are leaders within our creative ecosystems, our humanity depends upon the things we stand for. Poets often use our words to stand on issues that we are called to. Take how I open every open mic with the same haiku that questions equity through racial discomfort:

A Black Haiku

Where can we be black?

instead of justblackened out

where can I be . . . me???

There is an art to powerful messaging. I often pair a haiku exercise with the top ten literary themes so we can explore how words can serve a greater purpose. I encourage my students in all our creative endeavors to explore where they can be themselves. Most of the time, they are still learning how to be themselves. So their writers’ voice often echoes the things they go through as they slowly walk into adulthood. They are not shy to question the world, disrupt heteronormative narratives, and bring their radical imaginations to the page.

Writing allows us to communicate in ways that we would not imagine. When teaching, I try to find a way to open language so that students can explore ideas experientially. An activity for a New York Public Library workshop I created entitled, America is Me, America is Not Me, requires us to look at D.L Warfields’ installation, American Flag remix, for inspiration.4 We reimagine the various relationships individuals and communities can have through reclaiming storytelling. We generate one-line stories in response to the artwork, then create resting lines of 10 words or less which will springboard into a poem later.

Writing allows us to communicate in ways that we would not imagine. When teaching, I try to find a way to open language so that students can explore ideas experientially.

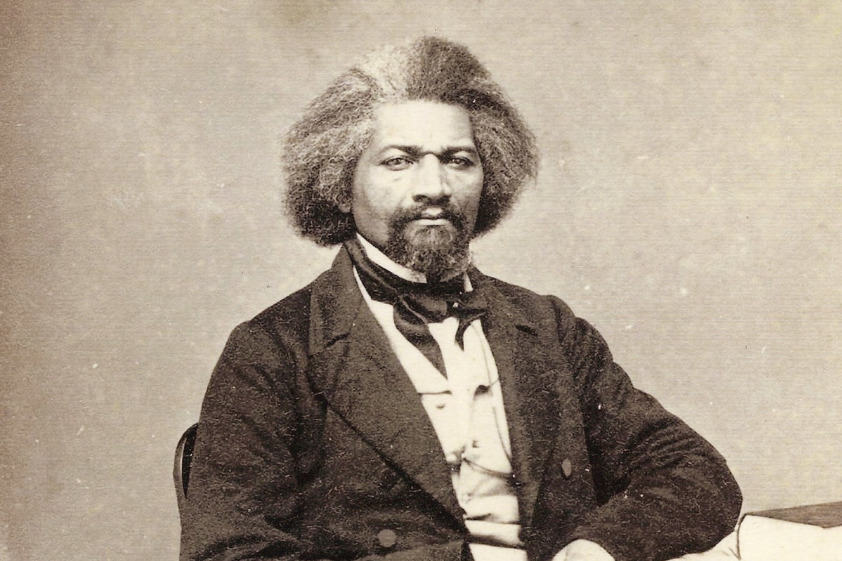

I also created an “America is Me” bingo board, in which each square is a poetic prompt, to extend our conversation and consider poetically what it means to live and be in America. As a Black man in America, these are the things I have no choice to consider, so I make space for that in my poetry and teaching. My students understand America’s complicated past and the risks that are at stake in positioning its future. They want to have a voice in that conversation. So I try to craft a safe and inclusive space for them to do so.

Students also understand how poetry allows people to discuss important issues in a way that other forms of writing may not. In crafting the poetic bingo, my goal was for students to think about their own experiences within America. It is through our poetry that we can see things a little more like James Baldwin when he wrote: “I love America more than any other country in the world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.”5 We try our luck at completing the bingo board to create a piece that poetically examines one of the narrative suggestions on the card or that weaves the themes together. Students take to the prompt in different ways. They write poems that mix their American dreams with news headlines and the things they love and question about America. Bella, 14 years old and a returning student to my workshop, embraced the America is Me, America is Not Me workshop prompts. She examined her relationship to America last year and recently came back this summer excited to share several updated stanzas including the ones below:

the 12-year-old girl that you force

to conceive is not old enough

to drive herself to the hospitalthis is america

you see,this is america

you see, we teach our children to hide

in corners from the bullets that you supply,

yet you will continue to blame

us, the future generation, for failing to be strong.

There is conviction here: about government control, women’s rights, and safety. As the poet reckons with her own understanding, she emphasizes the truths she uncovers through the repetition of the phrase “this is america.” She is right to go for it, to question and examine the world through poetic reflections. Poetry and social justice are linked habits that support the co-creation of social equity.

I think back to my earlier understanding of poetry as something formal and so far outside of my world that it created a barrier for accessing language. I didn’t realize early enough how my experience growing up Black was poetry. The way I looked at the Bronx was poetry. How I understood life is poetry. We can break the traditional understanding of reading and comprehension and, instead, translate through poetic vibrations. It is through this form of communication that we are able to break the nominal fourth wall, that we can recreate boundaries, examine relationships, and question society.

Lately I’ve been ruminating on the role of the artist, or as Nina Simone puts it, “What is an artist’s duty?” I think my artistic duty is to provide a path for my students to make their own connections to the page. It is to lead with my experiences so that they will be comfortable sharing theirs, and it is to lead with my heart.

Read more from this series:

“A Foundation in Activism: Reflections on the History of Teachers & Writers Collaborative” by Nancy Larson Shapiro

“Serious Play: Creating Liberated Spaces for the Making of Poetry” by Asari Beale

Footnotes:

1 Lopate, Phillip. Journal of a Living Experiment. Ed. Phillip Lopate. New York: Teachers & Writers Collaborative, 1979. 32. Print.

2 “More than 101,000 New York City Students Experienced Homelessness in 2020-21” Advocates for Children, 08 Nov 2021.

3 Derricotte, Toi. The Undertaker’s Daughter, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2011. Print.

4 Howard, Javan. “The Art of Powerful Messaging.” New York Public Library.

5 Baldwin, James Notes of a Native Son. Beacon Press; 1st edition (November 20, 2012)

Javan Howard is a poet and writer from the Bronx, NY. He is a Teaching Artist Project Lead Mentor, and a Teaching Aritst for Community-Word Project. Jay believes that the lived experience is the ultimate teaching tool and uses poetry as a social forum to foster discourse about love, culture, and identity. He has facilitated workshops with The New York State Office of Children and Family Services, Voices UnBroken, Community-Word Project, Teachers & Writers Collaborative, and Wingspan Arts.