T&W Magazine editorial board selected Sue Granzella’s “Voices in the Dark” as the 2021 Bechtel Prize runner-up. This year, the prize was awarded for an innovative virtual creative writing project.

The Bechtel prize is named for Louise Seaman Bechtel, who was an editor, author, collector of children’s books, and teacher. She was the first person to head a juvenile book department at an American publishing house. As such, she took children’s literature seriously, helped establish the field, and was a tireless advocate for the importance of literature in kids’ lives.

“Today, we’re going to start reading and writing poetry. Poems are like raisins. They have words, and details, and description, just like narrative writing. But all the extra words have been taken out, leaving only the sweetness. Just like a raisin.”

When we left school last spring not knowing we wouldn’t return, it felt harsh, cruel, as if the cords that connected us to one another had been hacked through with a machete. I will never forget the first time contact between me and my third-grade students was established. I emailed parents in both Spanish and English, unsure if the addresses were even valid, sending links to a video platform where I wanted kids to leave a check-in. We’d only used the website once; would nine-year-olds even remember how to log on? Lying in the dark late at night, I hit “refresh” over and over, desperate for something to appear. When it finally did, when the video greetings started trickling in, I cried. It felt as if we’d each been rocketed to the moon, and had found each other wandering around up there.

Now, it’s been almost a year, and educators walk a tightrope each day. We are cheerleaders, striving to motivate but not burden children already flattened by stress and depression. We want to be upbeat, a balm for their anxieties, yet still signal a willingness to listen to their heavy feelings of fear and loneliness. We want to help things feel “normal” when their world is anything but.

Here in California, after months of isolation, the blistering heat of late summer ignited dense forests. The friendly blue sky transformed, becoming our enemy: a suffocating, dark orange blanket pressing down on us, sucking away the air we needed to breathe. For weeks, the air-quality app on our phones screamed, “VERY UNHEALTHY.” We rarely ventured outside. In late October, roaring winds toppled trees and crashed Bay Area power and internet, canceling at-home classes for a day. The next morning, the big eyes and nervous chatter of my young students told me that balances had tipped, that taut springs had snapped. My students’ check-ins were tinged with a frantic energy.

“We have the pandemic,” began eight-year-old Alan, counting off on his fingers. “And then the protests. The heat wave. The fires. Then the smoke and the bad air. Now the wind, and the power outage. I feel like I’m trapped in a box that is getting smaller every day.” That’s when I decided to teach a unit on poetry. We began on the Monday after Thanksgiving.

My split-screen monitors allow me to view my young students, as well as whatever image I’m projecting. I scanned the array of young faces, some still with gaps where their baby teeth used to be. An eight-year-old was typing into the chat how many days remained until her birthday. A black rectangle hid the nine-year-old who attends class every day but stopped showing us her face in early September. A child whose home rests on pavement set his virtual background as maple trees, and all we could see was his head poking out from a jumble of red-orange leaves. A few kids were burrowed into their respective mounds of blankets, no matter how many times I’ve begged them over the past month to sit up instead of lie down.

Always, the tightrope. How to nurture desire, without adding pressure? I picked up the visual aids I’d retrieved from my kitchen, a raisin and a grape. Then I placed my hand under the document camera, the bits of fruit in my palm. “What do these have in common?” I asked. “They’re both fruit!” “They’re both good!” I explained. “A raisin is a grape. They’re both the same fruit. It’s just that the sun shone brightly on the raisin, heating it up until all the extra water was gone, leaving only the sweetness. “Today, we’re going to start reading and writing poetry. Poems are like raisins. They have words, and details, and description, just like narrative writing. But all the extra words have been taken out, leaving only the sweetness. Just like a raisin.”

Then I displayed the text of Patricia MacLachlan’s full-length book, called What You Know First, which I’d typed out and affixed to a Jamboard, along with a sprinkling of the book’s illustrations. When I was done reading, I asked if any words or images jumped out at them. They unmuted themselves, and I heard city kids calling out “horses breathing puffs like clouds in the air” and “how soft the cows’ ears are when you touch them.” I inhaled deeply. Almost every day, I am filled by both pain and wonder, the two intertwined in a gnarled mass both hideous and beautiful. These young people, crammed into bedrooms with crying siblings and barking dogs and feeble Wi-Fi, still try to do what I ask. It refuses to be quenched, the drive to grow, to seek, to hope.

On Day Two of the unit, I flipped through the poetry books I’d grabbed from my classroom back in August. Following writer Georgia Heard’s advice, I searched for poems that are short, accessible, and relatable. I typed out Aileen Fisher’s “Hideout” and Myra Cohn Livingston’s “Finding a Way,” pasting them onto colorful Google slides. After reading each poem aloud, I asked three questions:

- How do you feel inside when you read it?

- Does it remind you of anything in your own life?

- Why do you think the poet wrote this?

We talked briefly about why kids might hide, and about making friends. When I announced that it was free-write time and kids started pawing through the giant zip-lock bag of materials I’d delivered to each of them back in August, I heard a voice.

“Do we have to continue the true story we were writing last week? Or can we write poetry?”

I hadn’t planned to delve into actual writing of poetry until Day Three. Thrilled, I said, “Sure! You can write poetry if you want.” Writing time is one of the sweet spots of distance teaching. Students grip pencils and flip notebook pages and whisper to themselves as they reread their work, and for those moments, things feel closer to normal than at any other time. When I announced the end of class, Alan—for whom English is a second language—asked, “Can I read what I wrote? It happened in kindergarten.”

My dear friend

You were a shy one back then.

I asked you your name

You held up your nametag

But I couldn’t read.

Sumit, born in Nepal, could barely contain himself. “Wait! Before we end, could I read this?”

I don’t know what to say…

Will you be my new friend?I saw you on the bench

then I saw you on the swing.

I never had a friend

in this new school.

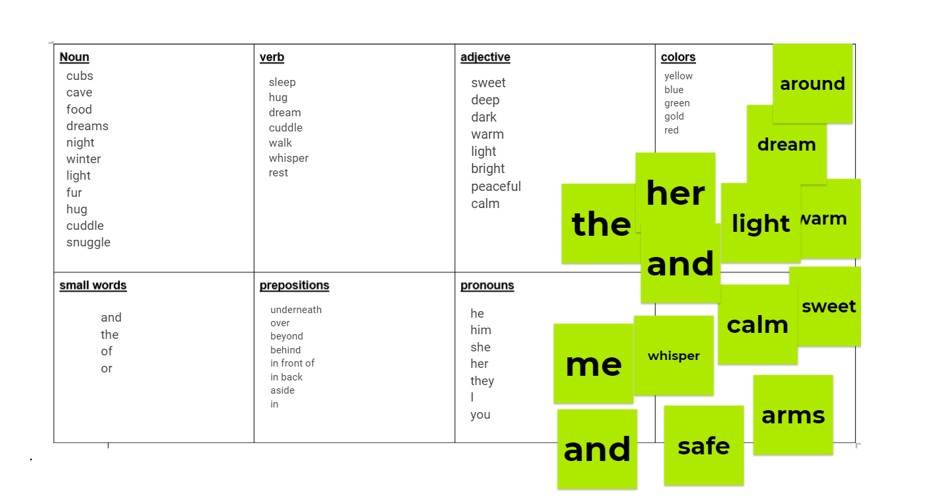

The struggles of distance teaching are agonizing, but the tiny victories become magnified. My spirits soared. And then it was Day Three. Adapting a lesson from Georgia Heard’s Awakening the Heart to make it work for distance teaching, I created a four-by-two grid on a Jamboard, and labeled each box. There was a section for nouns, verbs, adjectives, pronouns, and prepositions, even though most kids still couldn’t distinguish a noun from a verb. Two more boxes were titled simply “small words” and “colors,” with the last cell left open for “miscellaneous.” The day’s poem was “Grandpa Bear’s Lullaby,” by Jane Yolen, a short, illustrated verse about bear cubs hibernating with Grandpa. After reading it twice, I asked how the poem made them feel.

Cozy.

Safe.

Warm.

Peaceful.

Then I directed them to underline on the Jamboard the words that had helped create that feeling. They called out words they’d underlined.

“Deep!” I heard. “Dreams! Sleep! Cave!”

At first, I tried to get them to identify the part of speech of each new word, but kids were tossing words at me so quickly, I didn’t want to break the momentum. I just typed each under its respective heading. The next step, I figured, would stretch especially the many students who are still learning English.

“Now, what are some words that are not in the poem?” I asked. “What other words do you know that also help you feel safe, cozy, warm, and peaceful?”

Sweet. Hug. Calm. Whisper. I added those words, and others, to the word bank.

The final step before turning them loose was to model how the word bank could help them draft. I typed individual words onto Jamboard’s virtual “post-its.” Then I dragged the post-its into rows, read the words aloud, articulated my thinking (Hmm… the word ‘sweet’ sounds more like my mom. Maybe I’ll use that instead.), re-arranged post-its, and finally settled on a three-line verse that I read to them. “Now it’s your turn! Just play around like I did, and let us know if you create something you like.” Then I clamped my mouth shut, hoping that even the shakiest readers could come up with something to make them feel successful. With virtual teaching, when we’re all together and I tell my third-graders to get to work, I sometimes swallow tears as I watch their reactions. The children are so lonely and so desperate to connect that they tend to respond with a docility not typical in the regular classroom. But this day, I was excited instead of sad. The activity was productive, and their questions, eager:

Can we add more words that aren’t on the list?

If I want to write in my notebook instead of on the Jamboard, is that okay?

What if I get an idea in my head? Can I just write that, without using the chart?

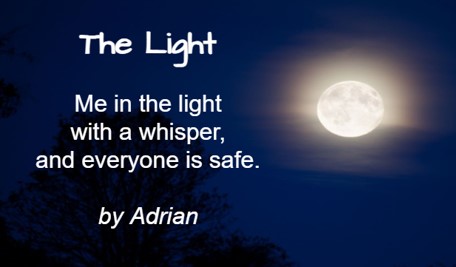

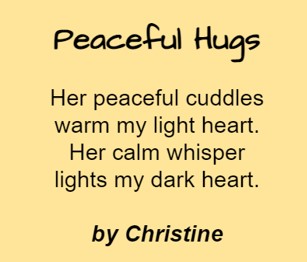

When a few kids announced with shining faces that they had finished, I wasn’t prepared. Fingers flying, I whipped out a blank Google slide, and posted it under the title: Type your poem HERE. Later on, once the day’s video class time was done, I clicked on the work of the several kids who had finished their draft.

And I gasped.

Third-graders typically write of puppies and playgrounds, happy stories of birthdays, of cousins, maybe even of trips to visit family in Mexico. Their crayoned illustrations bear smiley-face suns, rainbows and hearts, recess balls arcing through blue-scrawled sky. But the writing before me was stark, stilling. These children were not writing of concrete objects and events. Their topics were blurrier, more malleable: darkness, worry, and fear, but also light, safety, and comfort. To replace the sunshiny illustrations typical of “regular” school, students inserted background photos of the deepest night sky, of moonlight, of waves upon the ocean. One child asked me if it was okay to set her picture as the Buddha. It felt as if I was teaching a variant, parallel species, one that is familiar to me but also utterly foreign. I read with my hand over my mouth.

When the Light Comes

by CamilaRight now it’s dark

and we might feel like we are

trapped

but when the light comes

we will be free,

a bright hug

like the wind

blowing on a tree.

You will let the wind touch your face

without having to worry

about not seeing friends or family.

You will be in peace.

It will be light

we might not know when

but when the light comes

we will be us again.

(Note – These are the EDITED versions of their first copies, since the first copies no longer exist. Our editing conferences focused on line breaks, spelling, capitalization, and formatting.)

I read the first few, then ran downstairs to read them to my husband. Even he looked floored, fueling my excitement.

“This is not how little kids usually write! ‘It’s okay if you’re in the dark’? This is incredible.”

I ran back upstairs, and began texting the parents of my tiny poets, requesting appointments for one-on-one writing conferences. I couldn’t wait until the next day; my response had to be immediate, letting them know their poetic voices had been heard. I wondered if the kids would be disappointed that their teacher had called them back to “school” even though they were supposed to be done for the day. But one after another, the parents assured me that their child would be excited to get individual time with me. Telling each student that poets decide how many words to put on each line, I explained that they want certain words or ideas to stand by themselves to be more powerful. I helped them with spelling, and finding extra words that really weren’t needed.

“Remember the raisin?” I asked.

The final step was showing them how to format the text as an overlay to the picture. Then I said, “You’re done! What do you think?”

“I love it!” was the usual reply.

When I finished the last writing conference at 5:30 p.m., I began copying and pasting the finished poems into the Google slideshow I’d named “Poetry Anthology.” My original plan for the anthology had been to include each poem we studied in class, and to give the link to the kids so they could read familiar text. But teachers know to keep feeding a fire once it has ignited, so I knew I had to include their poetry and let them read each other’s creative work.

During the next day’s writing class, I was Cheerleader Extraordinaire, bubbling over with enthusiasm to present what they had done. After each poem was read and the third-graders praised their classmates’ work, I jumped into the day’s lesson on Langston Hughes. When it was time for the free-write, the chattering began and it was as if my laptop screen had become porous, the kids’ energy passing through it to permeate me.

I’m writing another poem!

I’m almost done with mine from yesterday!

I know what picture I want!

For writing homework later, can I write poetry instead of the journal page?

Poetry swept us through the weeks until winter break. During small-group reading classes, I asked kids to choose if they preferred starting a new nonfiction book or reading from the website that offered poetry books. They all opted for poetry. In Google Classroom, I found messages saying, “S., I made a poem for you because we are friends,” and “I made a new poem called ‘The Love Poem’!” and “I’m done with my POEM!!!!” On the day my back went out and the kids had a substitute teacher, they took a survey on “favorite dog breeds”; I returned to find two pug poems in my inbox. One child wrote an Elf-on-a-Shelf poem. Another cried when a classmate left our video-meet before the first child had the chance to read his friendship poem to his friend.

This is the final evening of our two-week winter break. I checked Google Classroom last night, and saw that one student had sent me four new poems, written during break. We’re moving into a new unit of study—persuasive writing—but I suspect that the poetry flame will keep burning for a few children, and that I’ll occasionally receive poems in Google Classroom, poems I will add to the class anthology. Nothing has changed in the last month. The pandemic still rages. The workload of distance-teaching is still overwhelming. Children are still lonely and stressed, stumbling around in the dark. But poetry may have pierced the darkness for my students, just the tiniest bit, with its flickers of light, its hints of beauty. Because darkness obscures sight, but it won’t silence voices. Even when all they can do is whisper.

Sue Granzella has taught for 32 years at Title I schools in California’s Bay Area. Her writing has been named Notable in Best American Essays, and she has won the Naomi Rodden Essay Award and a Memoirs Ink contest. She has also won numerous prizes in the Soul-Making Keats Literary Competition, a contest for which she is now a judge in the Humor category. Sue’s writing has been published in McSweeney’s, The Masters Review, Full Grown People, Gravel, Ascent, Citron Review, and Hippocampus, among many other journals.

Sue has completed a collection of essays about teaching, and is searching for a publisher. In 2020, she began a pandemic blog called The Extrovert Chair. Sue loves baseball, stand-up comedy, hiking, road trips, and reading the writing of 8- and 9-year-olds. More of her writing can be found at www.suegranzella.com , or at her blog at www.suegranzellablog.com.