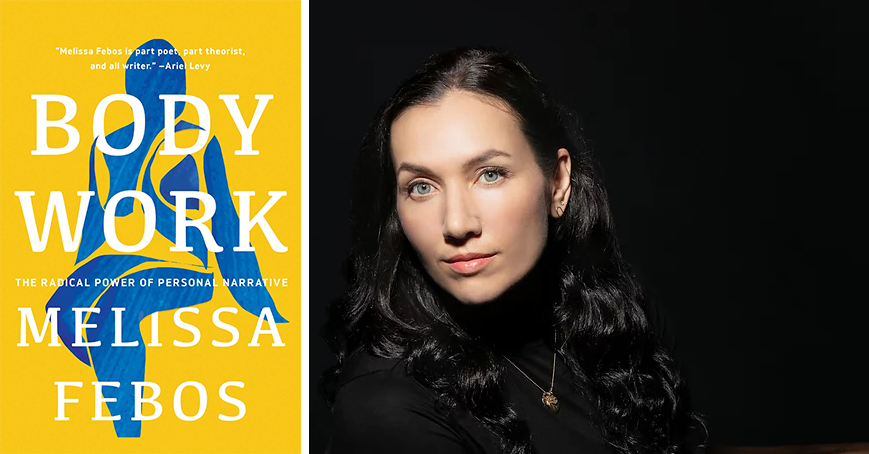

Melissa Febos is the author of four books, including the nationally bestselling essay collection, Girlhood, which is a LAMBDA Literary Award finalist, winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award in criticism, and named a notable book of 2021 by NPR, Time, The Washington Post, and others. Her craft book, Body Work (2022), is also a national bestseller, an LA Times Bestseller, and an Indie Next Pick.

The recipient of a 2022 Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship, a 2022 National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship, and the Jeanne Córdova Nonfiction Award from LAMBDA Literary, Febos’ work has appeared in publications including The Paris Review, The Sun, The Kenyon Review, Tin House, Granta, The Believer, McSweeney’s, The New York Times Magazine, The Guardian, Elle, and Vogue. Her essays have won prizes from Prairie Schooner, Story Quarterly, The Sewanee Review, and The Center for Women Writers at Salem College. She is a four-time MacDowell fellow and has also received fellowships from the Bread Loaf Writer’s Conference, Virginia Center for Creative Arts, Vermont Studio Center, the Barbara Deming Memorial Fund, the BAU Institute at the Camargo Foundation, the Ragdale Foundation, and the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, which named her the 2018 recipient of the Sarah Verdone Writing Award.

Febos co-curated the Mixer Reading and Music Series in Manhattan for 10 years and served on the Board of Directors for VIDA: Women in Literary Arts for five. The recipient of an MFA from Sarah Lawrence College, she is an associate professor at the University of Iowa, where she teaches in the Nonfiction Writing Program.

Lizz Dawson spoke to Melissa Febos about teaching writing, creative nonfiction, and her recent craft book, Body Work, over the phone on July 28, 2022.

Lizz Dawson (LD): One of the things I admire so much about you and about your most recent book, Body Work, is the way you advocate for creative nonfiction, as I’ve often found people don’t quite understand the genre and how expansive it is. I, like you, believe emphatically in the bravery of telling our stories—in the way they heal, in their political power. I’m wondering if you still find people questioning the legitimacy of creative nonfiction and how you respond when they do.

Melissa Febos (MF): At the beginning of the semester, I ask my students, “What is one thing you want to grow or change within your writing practice?” And so often they say, “Well, I really want to eradicate the personal and just focus on the journalistic aspects or the research aspects or the theoretical aspects.” It’s this really blunt, very old bias against personal writing and this idea of it as “less serious.” And the way that I approach that when I encounter it in my students is different than when I encounter it among my peers. If a student shares that in a class, I’ll just follow up by asking leading questions like, “Well, is that because you don’t enjoy reading personal writing?” And they’ll say, “Well, no.” And I say, “Is it because it’s less interesting to write?” And they’re like, “Well, no.” So I ask, “Well, why do you not want to write it?” And they don’t really know. Or they do know, but they don’t want to say it out loud because they recognize it’s not really what they believe. My questions are designed to get them to locate the source of their own thoughts, which is always the work that we’re doing in the classroom, right? And to reckon with the reality that there are other people’s ideas floating around inside of them that they didn’t choose and don’t agree with, and sometimes it is the opinions [of these other voices that] come out of their mouth, disguised as their own thoughts.

LD: Have you found that creative nonfiction is considered more respectable when it has these theoretical or more academic and researched aspects to it?

MF: Oh, absolutely. And these biases are totally independent of my actual experiences with literature and most people’s actual experience of literature. I love work that uses theory and uses research, and it’s one of my favorite modes to write in. But I don’t think it’s better. And, if anything, I think the relevance of it is contingent on the personal narrative.

LD: In your books and essays, you weave and balance the personal and the critical so well. Your first book, however, Whip Smart, is written solely as a memoir, and I know it got a lot of attention for its taboo subject matter. It provokes a worry I have personally about being taken seriously as a woman, especially when discussing sexuality. Based on your essay “In Defense of Navel-Gazing” in Body Work, I understand that your female students (and I’m sure gender nonconforming and trans students) are also worried about this. Personally, how have you dealt with others’ perceptions of you as you’ve become more and more successful? Is “being taken seriously” still something you worry about? And how do you approach students’ worries about these subjects in the classroom?

MF: That’s a great question, and the answer is that it has changed over time. When I wrote my first book, the factor of caring what people thought about me was much more present, and simultaneously, I had a strong drive to name things that weren’t polite or easy. It was very important for me to frame that book in intellectual terms and also not to flinch from the more explicit aspects of [my story]. I thought,“I’m going to include every single grody detail of that whole experience because people are going to tell me I can’t,” and I don’t regret it. But from a vantage point of giving many fewer shits about what people think of me (in particular, many fewer shits about what men think of me), it’s hard not to think, “Oh, I didn’t have to do all that.” And I’m not just talking about the gritty details of the book, but also how I worked really hard to sound smart, because I knew, of course, that I was going to be treated with tabloid curiosity once the book came out, and people were going to just ask me about spanking over and over again, which absolutely happened. All of my demonstrated intellectual inquiry did not protect me from that.

I think as time has gone on, my awakening as a human being in my life and in myself has happened alongside—and is totally integrated with—my process of growing and awakening as a writer, and that’s really reflected in my craft. The more I locate those other voices [inside myself] and figure out how to answer them, or extricate them ideally—those same voices that tell my students they should steer towards their super dry, theoretical discourse and away from their own stories and the things that actually drive them to write—the more my work feels like me. The more it becomes a mirror in which I can determine who I am.

My awakening as a human being in my life and in myself has happened alongside—and is totally integrated with—my process of growing and awakening as a writer . . .

It’s important to say, too, that with my first book, I was resentful of people asking me rude questions [about the content]. Now that I’m more secure in myself and I’m not looking to source my self-esteem from how other people express their perceptions of me, it allows me to be more generous. I can say, “People are nosy. I wrote a book about spanking and they’re going to have questions. That’s just understandable.” Sometimes, yes, they are absolutely reiterating these sexist paradigms that we’ve all grown up internalizing, but sometimes folks are just nosy, and you talk about something interesting and they want to know more, and that’s fine. It doesn’t mean I have to answer their questions, but I don’t feel threatened by it anymore.

LD: That’s such a compassionate view. I think it takes a lot to extricate ourselves from the anger that we feel because of the patriarchy to this more compassionate view. It reminds me of a beautiful moment in your essay, “The Return,” where you discuss how you have essentially written yourself into feeling beloved and seen for who you are. That admission feels so vulnerable to me. For me, it’s often harder to get to this more compassionate truth in my writing, as opposed to just staying angry or exposing my faults and traumas.

MF: Yes. I mean, anger is real but it’s a response to hurt or fear. And so I think for me, it’s only when I’ve found a way to get to that more primal emotion that I can change my relationship to [the anger]. And it really has been through writing that I’ve done that. It’s through stepping outside of the story of myself and redrawing it in an objective way, so that I can see myself the way that I see other people. The result is almost always that I feel compassion for myself, or really deep grief, or I don’t know, sometimes forgiveness, sometimes apology, but it is so vulnerable. It’s much more vulnerable than anger or the more analytical modes that I can work in that are much more comfortable for me. I had all these ideas when I was younger about what it meant to be tough or strong, and it’s just the opposite of what I thought then. Vulnerability is the hardest, bravest place to go.

LD: You talk about that resistance in Body Work. The point when, all of a sudden, we just feel like we can’t continue writing. You call it the “false wall,” and you write that you believe we stall because we know we’re near the vulnerable truth—or something we maybe don’t think we’re ready to see. But it’s crucial that we go there—it’s where the real writing begins. How do you get yourself started or keep yourself going when you can feel that you’re actively avoiding writing something? Are there any exercises you use with your students to get them through the false wall?

MF: My students often have come to graduate school because they want someone to make them do something that they won’t do on their own, which is a great reason to go to school. It’s why I went to school; it was totally worth it. So with them, I just say, “Keep writing.” I give a lot of prompts and assignments in my classes, which they find annoying sometimes, but I think that’s the best way to push through. Having some external power exerted on me to make me write through the discomfort, beyond the thing I expected, beyond the thoughts I’ve already had—that’s where the good stuff comes for me, and so I just make them write like crazy. And I give them positive feedback when they do it, which is absolutely genuine.

Also, a big part of my teaching is talking about how self-work, spiritual work, political work, psychological work—none of it is discrete from creative work, particularly in nonfiction. They aren’t discreet in life, and they aren’t discreet in writing. And so I say to my students: “You might not believe in therapy, but are you willing to do whatever it takes to make the best art you can make? It might require you doing something you didn’t think you believed in.” Whether that’s therapy or having a spiritual practice or having a conversation with someone that you hate, in theory.

In my own practice, it helps to have such a deep well of evidence to remind myself that [writing through the resistance] is worth it. I have persevered into that unknown space in my work many times, and I have always been rewarded for doing so by the satisfactions of what I have created, and the way [those satisfactions] reverberate through my life, my relationships, my teaching, and even through my body. I also have been blessed with this weird, intense urge to work shit out on the page and in art. It is the primary place where I am honest with myself, where I heal from things, where I integrate, and truly where I do my best thinking.

LD: You’re fairly open about being a spiritual person. Is this something you bring into your classroom, and, if so, do you ever get pushback?

MF: Yeah, I totally do [bring spirituality into the classroom], and I think it’s helped by the fact that I’m not religious. I’m not interested in, nor would I try to push religion on my students. But we’re talking about writing, and writing is a spiritual practice for me, and it is through spiritual practices that I connect with my creative practice. So I don’t know that I could do my job without spirituality being a part of it.

I remember when I was going on the job market after my first book came out, and I thought, “This book is probably going to hurt me as much as it’s going to help me get a job. Do I want to try to tailor it and mitigate those negative effects by spinning or hiding who I am?” And I made a decision not to, because I’m really bad at pretending to be anything other than what I am. Maybe that’s easy to say now, but I also feel really grateful for the opportunity to offer an example to my students of someone who can be tattooed and be a former sex worker and not be performing shame about any of those things in the academic space.

You have to write for the reader of best faith, the reader who most needs your work, and you need to do your absolute best work for that reader.

LD: You are exemplifying storytelling as an antidote to shame, and though we can try many things to create safe space in a workshop, as I’m sure you do, when we bring our genuine selves to a room, that invites others to bring their genuine selves, too. Is there anything else you do to create a sense of safety in your writing workshops?

MF: I have a whole little spiel that I give at the beginning of the semester. There are different versions of it for different classes, but the longest one is for workshop. The spiel, basically, in addition to defining what the atmosphere of the class is, sets really explicit boundaries for the class. I will talk about how my classrooms are a space of celebration, how we are here to describe things, not prescribe things. But then I also give ground rules and content warnings: “Don’t use any racial slurs in my class or in work, for example.” I tell them, “If something comes up for you, here’s how we’re going to handle it. If you have an issue with how I’m handling things, talk to me about it, and you will not experience negative consequences for doing so.” I say, “People always cry in nonfiction classrooms. People will probably cry in this classroom. If someone does, we’re not going to freak out and try to take care of them. We’re just going to let them have their feelings, and we’re going to keep doing whatever we’re doing.”

And everyone is encouraged to take care of themselves however they need to do so. And I tell them that it will probably take a certain amount of time to acclimate to the culture and the ground rules in the classroom, that I may give them corrections, and they never need feel embarrassed about that. Basically, I just try to set up an atmosphere where it’s okay for people to make mistakes, where everybody is trying to do their best and to support each other.

LD: What do you get most excited about in a class or workshop?

MF: Honestly, I am just so ridiculously excited at the beginning of every semester because I can’t believe I get to do this for a living, that I get to sit in a room full of artists and talk about books and writing, and I get to decide what books we read. It’s a ridiculous fantasy. If I could go back, I’d be like, “You little weirdo who doesn’t know any other artists and thinks that you’re completely alone in the way that you experience reality, who has also made a lending library of your bedroom which you force your family members to borrow books from—get a load of this.” I feel just incredibly fortunate all the time. Similar to how writing is the place where I do my best thinking, it’s in conversation with other people that I get most excited and feel most grateful for how I get to spend my life. And it’s also where I figure out how I do what I do. Through teaching, I’ve learned to understand the mechanics of writing and by the mechanics, I mean every aspect of it, including the emotional. I didn’t know how to articulate it before, and I didn’t understand how it worked, and I think I do now almost entirely by virtue of my experience teaching.

LD: What do you find the most disheartening or challenging in a room, and how do you approach it?

MF: That’s tricky. I’d have to think about it a little more, but I will say that one of the things I find disheartening is something I’ve seen increasingly in students, where they are bringing the imagined criticisms of a bad faith reader to the desk with them when they’re doing the first draft. Basically, they’re already thinking, “What is that person on Twitter going to say about this when I publish it?” It is a preoccupation with others’ perceptions. I try to encourage them as much as possible: be conscientious in your work. Be conscientious of your reader, of your potential readers, of all of your past selves, but do not write for the bad faith reader. You have to write for the reader of best faith, the reader who most needs your work, and you need to do your absolute best work for that reader. Exile the thoughts of the person who is looking to invalidate the art that you’re making; you can’t make art that way. Or it will be a brittle, sad version of what you would’ve done if you had imagined the loving reader who is grateful and interested in what it is that you actually are trying to communicate. And I do find that students respond to the instruction to not think about it.

LD: I’m also wondering how you balance teaching and writing so well. This seems to be a common struggle among teaching artists: balancing their creative work with their work in the classroom.

MF: I mean, it’s really true. I struggle with it. I guess that’s not the same thing as doing it well; I guess I do it well if I’m writing books, but I find it painful. It’s really hard because I’m a very hard working student, and I bring that hardworking student energy to being a teacher. And I love teaching. I just want to give it my absolute best all of the time, but giving writing my absolute best means I can’t always give teaching my absolute best, and so that hurts a little bit. My teaching and writing do feed each other and nourish each other in many ways, but time is finite, however elastic. And so sometimes I have to choose the work first, and in the end, I think that benefits my students more because if I’m not doing my work, I get really grumpy, and I specifically get grumpy in my teaching, and then I’m no good to anyone. I have to feed myself first and then I can nourish other people.

LD: Students are often told that it’s imperative to write every day. Do you have a writing schedule?

MF: I have a schedule when I’m deep into something. Right now, I’m working on this new book, so I need to keep a consistent practice so I can stay fluent in it. If I stop working for a few weeks, I forget the language of the thing I’m writing and I have to relearn it, and it’s like starting a campfire over again. It takes a while. So that means that I write multiple days per week—not every day, usually, but multiple days per week. I usually work in the morning because that’s the best time for me, before the traffic in my brain gets too congested. I have my best energy first thing in the morning before I’ve spoken to anyone, before I’ve looked at my email, before I’ve observed anyone else’s desires or expectations of me. For example, this morning I got up and I worked for three hours, and I’ll keep that up pretty much all year round if I have momentum on something.

LD: What’s something that you tell your students when they put a lot of pressure on their writing and/or on getting published?

MF: I have to say—and this is pretty mundane because it’s a thing that all my teachers said to me because it’s true—that the writing is the best part. It absolutely is. Almost all of my writing dreams in terms of achievement have come true, and I promise you writing is the best part.

And I will say as an addendum to that: take your time. Don’t be in a hurry, and capitalism does that to us, but I have never been sorry that I took my time, and I have often wished that I had given myself the time that I really needed for something. It always feels like you’re behind, but you’re not. There’s no hurry. You’re right on time.

Lizz Dawson is a writer from York, Pennsylvania, living in New York. She is a nonfiction MFA candidate at The New School. Lizz has held positions at Creative Nonfiction, Story Magazine, and Teachers & Writers Magazine. She currently interns at The Center for Fiction in Brooklyn. You can find her work online at Story, Peatsmoke Journal, Bending Genres, Elephant Journal, and Hayden’s Ferry Review. You can find her newsletter, Hangry Ghost, on Substack.