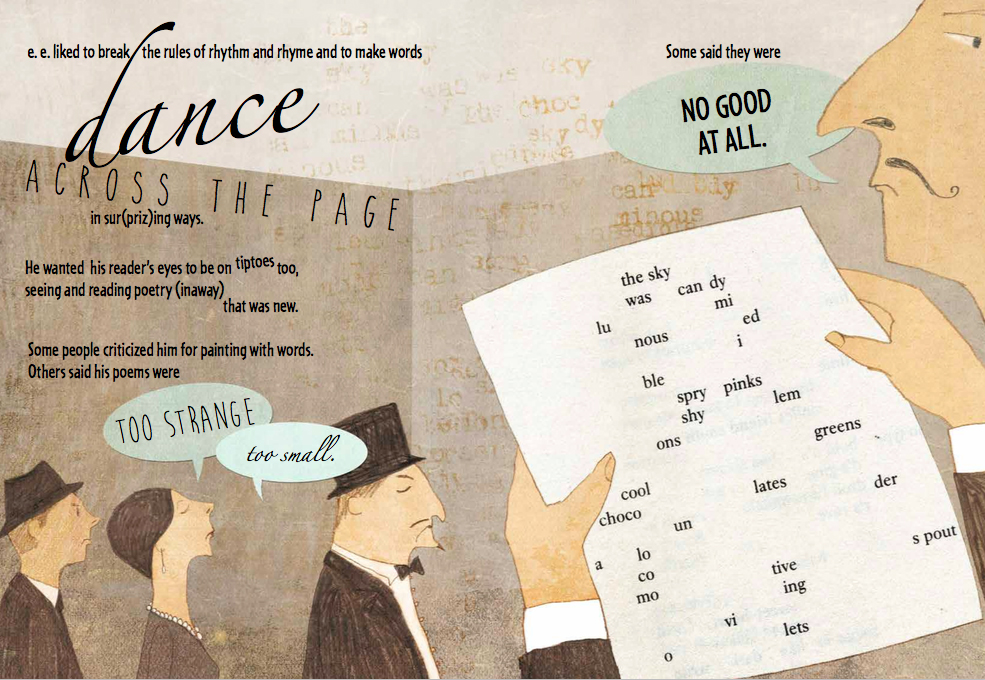

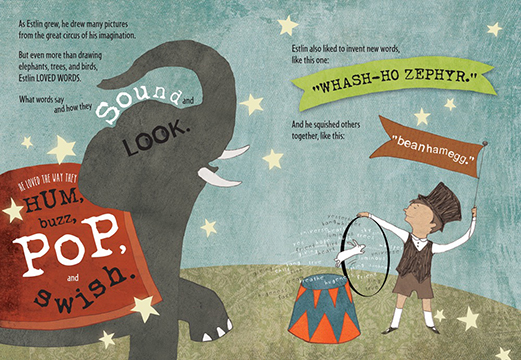

While working on the manuscript for Enormous Smallness: A Story of E. E. Cummings (Enchanted Lion Books, 2015), I searched for poems that would suit the audience and form of a picture book. It was trickier than I had anticipated. Even the poems that were “age appropriate” in theme or content seemed too experimental, and I worried that they might not hold the attention of very young readers. In the midst of this process, I happened to be teaching Cummings’ “the sky was candy” in a class at Brooklyn College, and one of my students suggested that I share this poem with my first-grade students. The students were captivated by it, and their enthusiasm inspired me to write a lesson plan that I published in a previous issue of Teachers & Writers Magazine. The poem also became a key moment in the book.

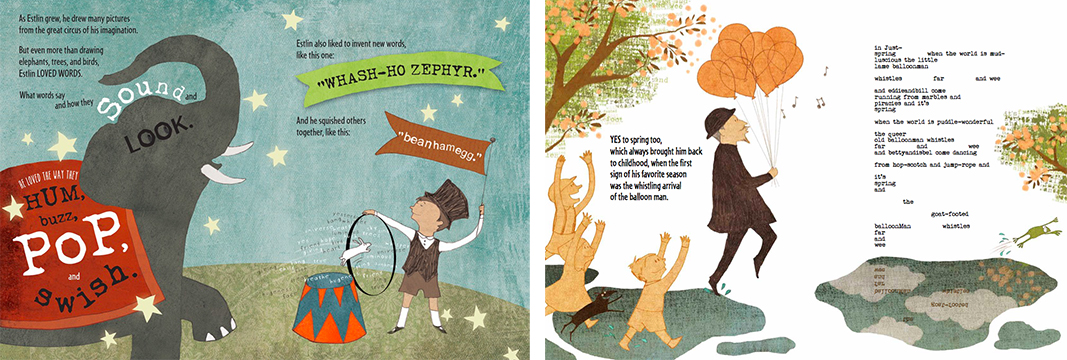

Another poem that was clearly a shoo-in was Cummings’ much-loved and widely-anthologized celebration of spring, “In Just-.” Upon rereading it, I was surprised that I hadn’t taught it before, and after an unsuccessful search for lesson plans online, I decided to write a new lesson and try it out with my second-grade poets in Manhattan. The following lesson plan works well with Enormous Smallness as an accompanying text, and I use these two pages as a lead-in to the writing exercise. It is easily adaptable for any grade level, from kindergarten to college.

- I start by reading “[in Just-]” with the class. I like to read it once aloud, and then ask for student volunteers. It’s not the easiest poem to read, but hesitations and pauses can be helpful in highlighting some of the unusual moves that the poem makes. If possible, project the poem onto the wall or board so that students can see and discuss the spatial arrangement of words on the page.

- As necessary, I pose questions about the poem to stimulate conversation: How does the speaker of the poem feel about springtime? Can you remember a time when you liked to play in mud puddles? Where does Cummings play with words or break rules? What do you notice about how the poet puts the words on the page?

- Allowing the discussion to follow its course, I intermittently identify the literary devices that I want to highlight and write them on the board. These can be easily adapted to suit age level or unit. For example, when a student points out Cummings’ use of “mud-luscious” or “puddle-wonderful,” I might say he is “squishing words together,” or I could use the term “kenning.” For the purposes of the writing activity that follows, I generally emphasize:

- Wordplay (squishing words together, kenning, parataxis, etc.)

- Onomatopoeia (“wee”)

- Play of form (free verse, composition by field, “projective verse”)

- Without becoming too bogged down in technicalities, I shift into a collaborative lead-in activity. Using a large sheet of paper or a SMART Board, I make two columns. I ask students to brainstorm “things” they associate with spring, and then, in the first column, I write their suggestions in the singular form. (For example, flowers become flower, umbrellas become umbrella.)

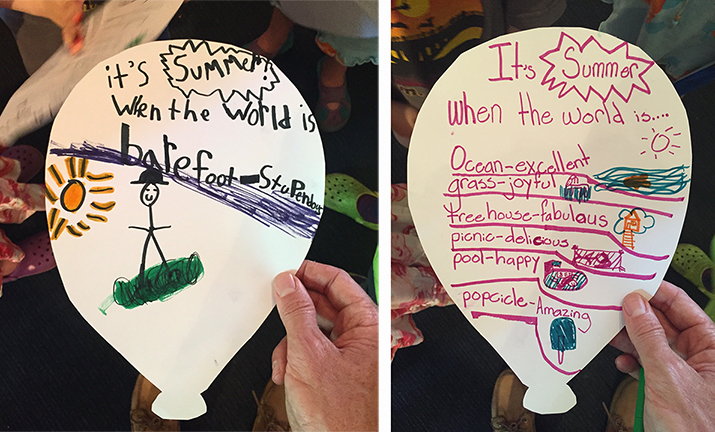

Note: you can use fall, winter, or summer as well, depending on the season, the mood, or student choice. - Then we brainstorm a list of adjectives that convey enthusiasm or excitement, and I write these in the second column. When working with second-graders, I ask for words that are similar to “wonderful” or “really great.”

- Once both columns are full, I write (or project) the following sentence: “It’s spring / when the world is ____-____!” I ask for volunteers to take a word from the first column and “squish it together” with a word from the second column. Students immediately sense the spark as you write things like “grass-fantastic,” “sunshine-spectacular,” “rain-amazing,” or “coconut-preposterous.”

- When the energy shifts and the “making impulse” kicks in, I keep the directions as simple as possible and try to float a feeling of “permission” in the air. Some students need more clarification or guidance, while others need to be set free immediately. The basic instructions are:

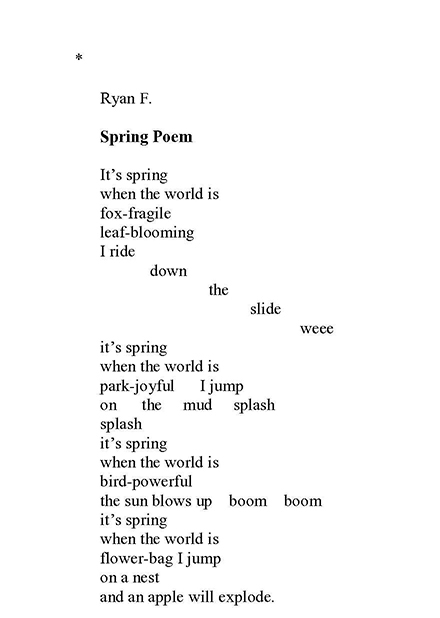

- Write a poem about spring (or summer, fall, winter) inspired by E. E. Cummings’ example. Using the brainstormed lists—or inventing your own—squish some words together and play with the placement of the words on the page. See if you can include an example of onomatopoeia like E. E.’s “wee.”

- Think about what you see, smell, hear, touch, and taste in this season. If you’re not sure how to get started, or if you like this opening line, begin with: “It’s spring / when the world is _____-_____” and then keep going! You don’t need to decide what you are going to write about—just jump in and let your pencil find it.

If you are working with very young writers or writers with special needs, the poem can be simplified to a short list of hyphenated words. I have collaborated with the illustrator of Enormous Smallness, Kris Di Giacomo, on versions of this lesson that incorporate a visual element.

With older students, I like to point out Kenneth Koch’s observation that “a poem is an experience and not a description of an experience—a communication of a lively, and even of a rambunctious kind.” In other words, I tell them, let your poem evoke this season through active language and vivid sensory detail. You might remember what this season meant to you when, as a child, you were attuned to the particular bite or sniff or feel of a season, or when you felt the excitement of weather rather than seeing it as an impediment to your commute. That said, your poem also could be a rant or a parody of Cummings’ exuberance.

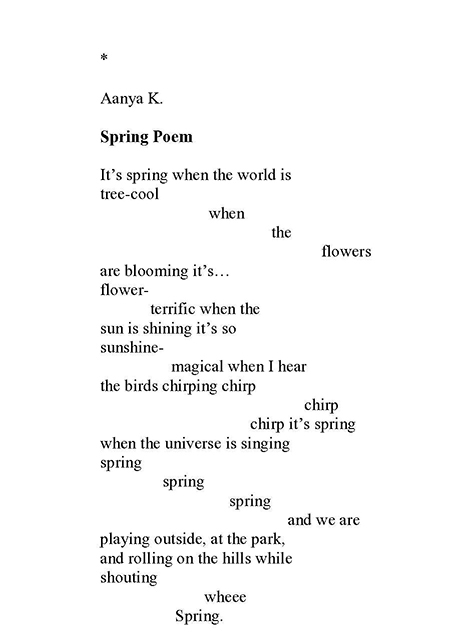

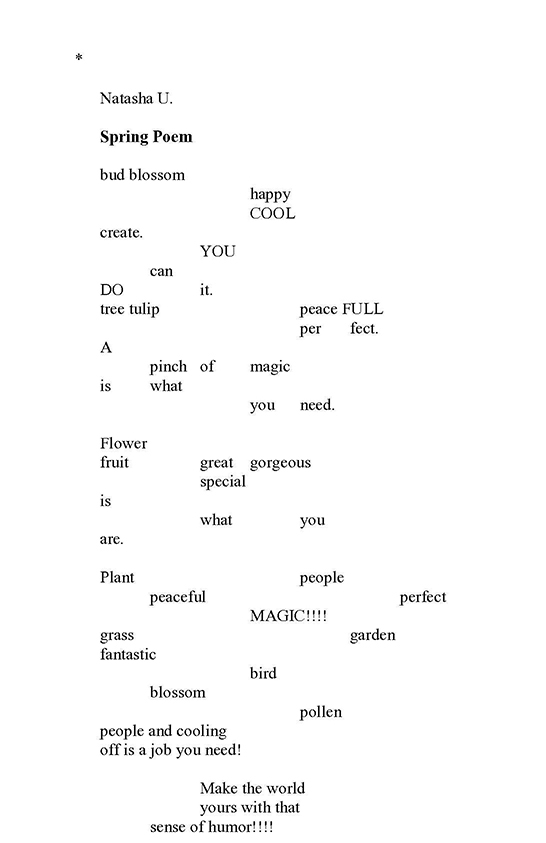

I also like to pair a “famous poem” with a student poem from a previous residency or class. Many students seem to be more inspired by these examples; they can stimulate hesitant writers with a sense of “I could do that” or “Ooh, that’s hot.” Sometimes I give my older students examples from my early elementary residencies, because they awaken a sense of playfulness and possibility. To those ends, here are some poems from my second–grade writers at PS 51 in New York City, written last spring.

e.e. cummings

Matthew Burgess is an Associate Professor at Brooklyn College. He is the author of eight children's books, most recently The Red Tin Box (Chronicle) and Sylvester’s Letter (ELB). Matthew has edited an anthology of visual art and writing titled Dream Closet: Meditations on Childhood Space (Secretary Press), as well as a collection of essays titled Spellbound: The Art of Teaching Poetry (T&W). More books are forthcoming, including: As Edward Imagined: A Story of Edward Gorey (Knopf, 2024), Words With Wings & Magic Things (Tundra, 2025), and Fireworks (Harper Collins, 2024). A poet-in-residence in New York City public schools since 2001, Matthew serves as a contributing editor of Teachers & Writers Magazine.

One response to “When the World Is Mud-Luscious”

Thank you for your lesson plans. I am a 74 year-old retired teacher. I taught English and Spanish (mostly). I had a wonderful high school teacher who introduced us to ee cummings. I enjoyed reading the childrens’ poems today. They were terrific!