This article previously appeared in Teachers & Writers Magazine, Volume 40, Issue Number 3, page 25.

All of us have dreams, whether we remember them easily or have to work to remember them. “Let’s write a poem,” I tell my high school students, “based on a dream that we’ve had, no matter how strange or complex or simple the dream is.” What we’re after is a poem, but a byproduct of this exercise times occurs when students continue to record their dreams in the journals that I require them to keep. I’ve also done this kind of writing with little kids (they can dictate their dreams to you) and with college students.

Usually I seek to get the students warmed up and excited about their dreams by asking, “How many of you have dreams?” Just about all of them raise their hands. Then I might tell a dream of mine, including a “recurring” dream that I had in my teens: I’m driving my car towards an intersection, and when I apply the brake pedal to come to a halt at the stop sign, the car won’t stop. Finally I pull up the emergency brake and come to a skid-stop in the middle of the crossroads, only to look to my right and see a police cruiser parked across from me at the curb. I had this dream from about the age of 16 onward, until I moved to New York in my early 20s and stopped driving.

We’ll go on to tell a few of our dreams, but just a few—I don’t want the students to burn out on the idea. Often, if there’s time, I’ll ask them to write down a dream then and there, or get started on the one that they’re ready to write. They can finish it at night and type it up. Or I’ll give them a couple of days to finish it. Generally, this is not an assignment that they have to agonize over. It’s all there already, in their head and in their body. All that they have to grapple with is the form of the dream poem (free verse-but more of that later).

A dream “speaks” in images––the pictures that come to us in the night. All that really has to be done to write a successful “dream poem” is to transcribe to the page the images that appear in the dream. Let the dream tell its story, and write the story down as the images unroll, I tell my students, just like the scenes in a movie.

Students can choose to write down a recent dream. Or perhaps they’ll choose a dream that they had when they were younger, and that they still remember. It may well be a recurring dream. It seems to me essential that the teacher share one or two of his or her own dreams to model the assignment for the students.

Dreams show that the unconscious mind (which produces them) acts in a poetic way. I tell my students not to worry if the dream doesn’t tell a recognizable “story” as long as it is compelling enough to write down. Likewise, students shouldn’t refuse to write down a dream that seems idiotic or silly. Dreams have their own sense of humor, too, and it may be important to get a hold of that humor. Even a fragment of a dream can make a good poem.

In writing their dream poems, I ask the students to keep their lines short. (That doesn’t mean that the poem will be short; indeed, many of them turn out to be two or three pages in length.) If necessary, students can draw a line down the middle of their notebook page and not write beyond that line. We want the images to stand out in a way they can’t in prose and the short lines highlight the pictures in the dream. In addition, rhyme is forbidden. I want the students to write a free verse poem-and poems written in free verse do not have a regular beat (meter) nor do they rhyme. I ask the students to avoid rhyme and meter so that they won’t be tempted to sweeten up the poem or tone down its images or reject parts of the dream because they’re difficult to find rhymes for or to fit to a beat.

If people speak in the dream, I tell them, let them speak. If dogs fly, let them fly! Students should get in the colors, sounds, and textures of the dream. All of it is important. It’s better to put in too much detail on the first draft; the excess can be cut back in subsequent drafts, if necessary.

I ask the students to start the dream in medias res, as the Latin poets liked to say. That is, start it in the middle of the action, as I do in this example:

I’m walking down a dark road

lit by the moon. The trees and bushes

on either side lean over, as if

to follow my progress, as if they

were large animals sniffing me

as I move ahead.

The idea is to stop when we’ve said all that we need to say, or all that we can remember. There is no need to create a phony “Big Ending” for the dream (or for any other poem, for that matter). I ask them to keep the writing clear and simple, and to concentrate on bringing across the images that can be seen in the mind as the dream is remembered. Sometimes we aren’t sure what happens here and there in a dream. My advice is to write “as if” we remember. In other words, make it up! Who is going to know except the poet?

It’s a good idea to have students avoid the ending that goes, “But I woke up. It was all a dream!” Such an ending isn’t going to add anything fresh to a poem, and in fact will only detract from it. Better to simply stop the poem where the dream narrative ends, without forced conclusions, Technicolor sunsets, or blazing violins!

Generally I’ll encourage students not to talk about how they’re asleep and dreaming, but sometimes dreams are self-referential. If dreaming itself occurs in the context of the dream, I’ve decided, it’s perfectly acceptable for the students to use it. But (to repeat myself), get the students to avoid starting off with phrases like, “Last night I had a dream, and in my dream” or “then in my dream.” These kinds of cues only tend to foster the “it was only a dream” attitude, when what we are after is the aliveness of the dream.

Drawing a Dream

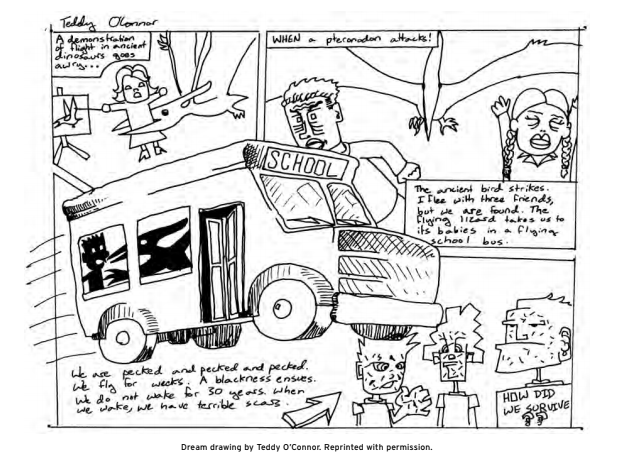

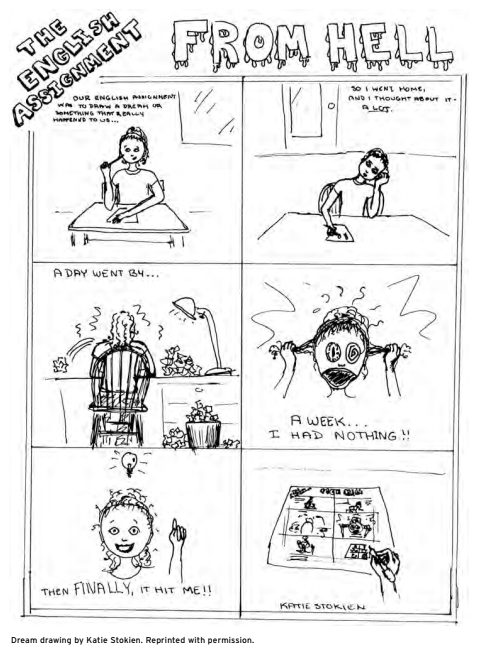

A variation on the idea of writing one’s dream as a poem is to draw the dream. I emphasize to students that this is not about artistic talent, but about framing the dream in another way. They can use stick figures for all I care, and sometimes they do. To describe this technique to the students I’ve shown them examples of the brilliant work that Dave Morice has done in his Poetry Comics books. His renderings can be seen as dreams or dreams of poems, and generally serve as tremendous inspiration to the students.

A dream can be drawn like a newspaper cartoon or like a comic book story with panels. It can also be drawn as one big artwork (we never use paper larger than 8.5” x 11” so that the finished drawing can be easily photocopied). It’s important that the students use black ink or heavy pencil so that the drawing will photocopy properly.

The trick in drawing a dream is to include a healthy amount of text, perhaps almost as much text as one would use in a poem, though the nature of the artwork will inevitably determine how much text is used. In any case, I always say to the students (and more than once), “Don’t only give me pictures. This drawing has to tell the story of the dream, and you’re going to have to put words into your drawing to do it.” Since this is not an assignment that lends itself to “redrawing,” unlike the dream poem, which can be rewritten endlessly, it might be a good idea to have the students write their dream poem first, then draw it.

If the student feels that the details or the narrative of the dream are overwhelming and simply can’t be shoehorned onto a single page, it can always run longer. Another way to “work” this assignment is to offer the students the option of picking a moment from the dream and illustrating that, again using words to support the visuals. Some of the best of these artworks have come out of the “dream moment” assignment. Often the “moment” summarizes the dream, and the words or poem give it context. Students can think of the “dream moment” as a single frame from the dream-movie, like the “freeze frame” in cinema.

Visual texts speak louder than descriptions, and I will content myself with offering some examples of these “dream drawings,” which will make it immediately clear what they do and what they don’t do. And obviously there are many variations that can be done upon this theme. In fact, it would be interesting to see if one or more enterprising students would volunteer to draw their dream in more than one format, maybe in even more than one style.

How to Remember Dreams

If the students need help remembering their dreams I tell them to try this technique: Before they go to sleep, repeat three times, “1 will have a dream and I will remember it.” Three times. They can keep a pencil and a notebook beside their bed so that they can write down the dream quickly if it awakens them during the night, or do it when they wake up in the morning.

Another trick is to keep a small, hand-held tape recorder beside the bed and to learn how to use it in the dark. Later on they can sit down at the computer and transcribe what they’ve recorded. If students get into the habit of recording their dreams, they will remember them more easily.

Psychologists tell us that everybody dreams. But what about the problem of those who say they can’t remember their dreams? If a student claims that this is his or her situation, and inevitably some of them will, then ask him to invent a dream that he could have had. Certainly he’s seen enough dreams depicted in movies or television shows or in comic books. She also may have read literary works that contain dreams. Students can draw on the ideas of these dreams (but shouldn’t copy them) for their own imaginary dream.

Further Thoughts

It’s a lot of fun to discuss the meaning of dreams with students, who are usually passionately anxious to figure out what their dreams are saying. (This can be done at just about any level of education.) If you know something about dream analysis, all well and good. If you don’t, you might open a discussion about dream folklore, batting back and forth received ideas like these: Nobody ever dies in dreams. If you die in a dream, you’re going to die in reality. People have dreams because of the foods that they eat. And so forth and so on. Students will have plenty to say about these shibboleths, and might just come upon some larger truths.

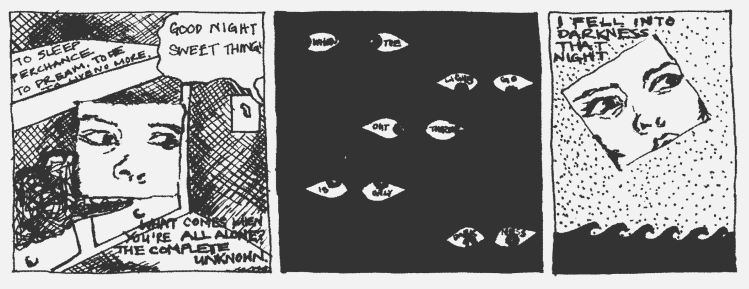

The poem is the text above reads:

A Dream

To sleep, perchance to dream.

Olivia Zaleski

To die, to live no more.

Good night, sweet thing.

What comes when you’re all alone?

The complete unknown.

When the

lights go

out there

is only

darkness.

I fell into darkness that night.

A darkness filled with dreams

of swimming fish and free floating.

Then one of the fish ate me and there was more darkness,

but a different kind,

a real darkness.

Ask your students if they’ve ever seen the dream books that are for sale at newsstands and bookstores (or bring one to class). In these books dream imagery is given fixed values, translations if you will. A fire means that something in your life is out of control, dreaming of a fork means that you have an intestinal disorder. Of course, I’m making up these nutty ideas, but some of the “equivalents” in the dream books are just as wrong and just as hilarious.

I know a little bit about Jungian dream psychology, but I’m not advocating that dream theory (anyone’s) be poured upon students at this stage of their development. Sometimes I’ll mention a few concepts that Jung talks about-the shadow, the animus, the anima. These are figures that appear in dreams, Jung says. The shadow represents those parts of our personality that we have repressed (a term that can be explained rather easily to the students), usually things about us that we don’t want to see. The shadow is always the same sex as the dreamer, often a grotesque of some sort, usually frightening and menacing. What is that “thing” that chases you in your dreams? (Analogies to Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde go a long way here; most students know that Mr. Hyde is Dr. Jekyll’s evil alter ego-his shadow.) The animus is Jung’s name for the masculine element in the female psyche; the anima the feminine element in the male psyche. What the students seem most interested in is another idea of Jung’s that I often pass on to them-that everyone and everything in their dreams is some part of who they are. This is a good enough reason to pay attention to the figures and situations in our dreams. Maybe this foray into what psychologists call “dream work” will whet their whistles for more information, but this I have to leave to another teacher.

Dreams might open an important window for students into their deep inner life. I have all my students keep journals, and I know that some of them go on from this assignment to write down their dreams on a regular basis. “A dream is a wish your heart makes / When you’re fast asleep” is what Walt Disney tells us in Cinderella. That statement isn’t very far from Freud’s theory of dreams as wish-fulfillment, but there is a long road to travel between Disney and what Freud called “the royal road to the unconscious.” Writing dream poems may get students thinking about taking that journey.

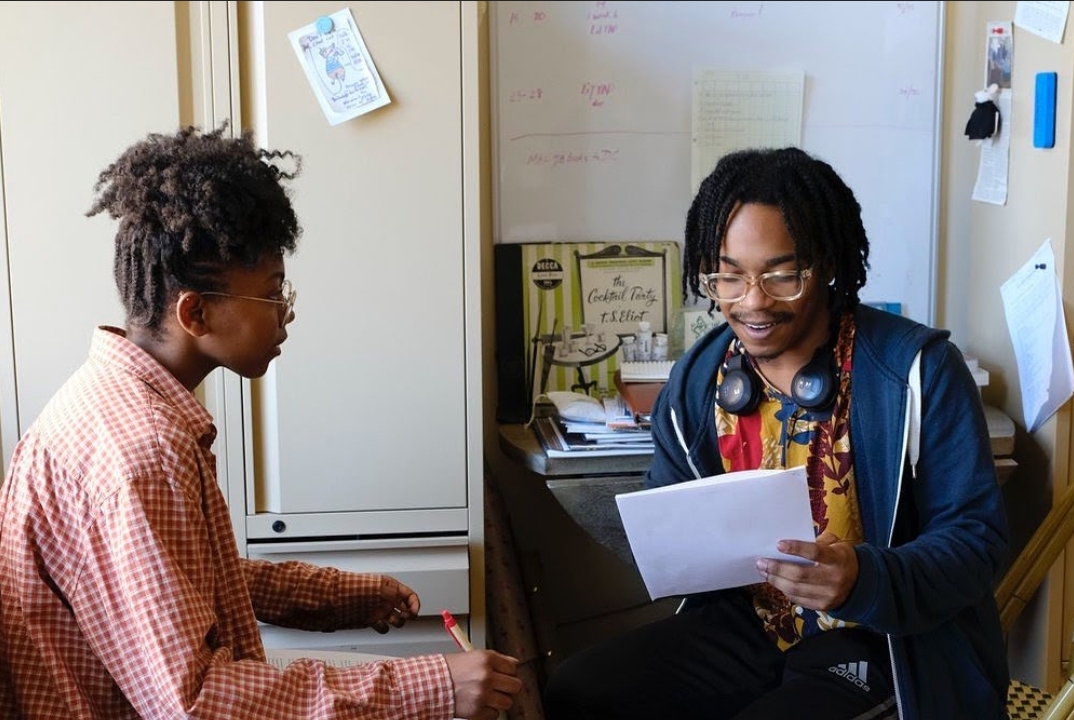

The text in the photo above reads:

"I am running through a bright green jungle peacefully bathing in the rich yellow sunlight. something is chasing me and I can feel its breath blowing on my back of my neck in thick, hot clouds with every leap I take I can feel its paws brush my heel. The silky leaves swat at my face faster and faster as I sprint further ahead. Then suddenly a waterfall appears in front of me, and I can see the water splashing and frothing below I can hear the things growl getting closer, and I slip I try to grip the rocks, but my shaking fingers just slide off. Panicked, I try to scream, but nothing comes out. Then, just when I begin to fall I see Peter Pan soar through the air. He catches my wrist just in time and smiles. Then I wake up."

Bill Zavatsky has published two books of poems, most recently Where X Marks the Spot (Hanging Loose Press). His co-translation (with Zack Rogow) of Earthlight: Poems by Andre Breton (Green Integer), won the PEN/Book-of the-Month Club Translation Prize. His revised co-translation of The Poems of A.O. Barnabooth by Valery Larbaud (with Ron Padgett) was recently republished by Black Widow Press. In 2008, he was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in poetry. He teaches English and creative writing courses at the Trinity School in Manhattan. Poet and translator Bill Zavatsky teaches his high school students to forge a connection to the deeply personal language of their dreams, mining the rich images to be found there for poetic inspiration.