I.

On the night of October 8, 2017, aptly-named Diablo winds from the east, gusting at as much as 70 miles per hour, carried embers over the mountains that separate Sonoma and Napa Counties in wine-country California. The resulting massive wildfires burned more than 5,000 homes to the ground in Sonoma County alone, most of them in the largest city and county seat, Santa Rosa. More than 100,000 people were evacuated.

Sonoma County has quite an active chapter of California Poets in the Schools (CalPoets), and of our contingent of poet-teachers at least five of us were moved to bring our skills—of all kinds, including that of eliciting poems from kids—to shelters to help in whatever way we could.

At first, the more immediate needs of those at the shelter precluded some of the CalPoets volunteers from doing any writing with the young residents there. “The thought of writing and/or sharing books with children at the Petaluma Fairgrounds Shelter appealed to me,” said teaching artist Sande Anfang, “but each time I went, the immediate needs of sorting, serving food, and general clean up were so immense that it seemed undoable to me.” Even so, Anfang noted that in her time at the shelter, she saw many children taking comfort in reading alone or with a parent.

Once the more urgent needs of those fleeing the fires’ devastation were met, CalPoets teaching artists stepped in to offer activities that might give children and teens affected by the disaster a way to talk about their experiences, or even just some temporary comfort or distraction. Teaching artist Pamela Singer volunteered at the evacuation center set up at the Santa Rosa Fairgrounds, where she taught young people a crash course on how to write a poem. CalPoets Sonoma County coordinator Meg Hamill organized a nature-based day camp for kids whose schools were closed due to the fires, drawing on her work at LandPaths, a nonprofit dedicated to fostering a love of the land in Sonoma County. Jackie Huss Hallerberg, another CalPoets teaching artist, facilitated several poetry activities at the camp.

In one exercise, Hallerberg invited young kids to decorate a “mini-me” wooden cut-out doll and then write or draw what was inside their hearts. Once the children had done so, she led them in reciting a group poem based on their heart drawings. With older kids at the camp, Hallerberg offered a lesson on haiku. Many of the kids who joined the lesson used the form to express their reactions to the fires that had upended their lives. Eighth-grader Ethan Davis, who lost his home in the fire, wrote the series of three, below. Hallerberg remembers that Ethan’s mother cried when she saw what he’d written, and said she could see that her son was showing the resilience that would get him through this experience.

After the Fires

grass flows like ocean waves

clouds shadow this land of ours

darkness smothers earthpain is just a thought

our mind creates it to protest

unnecessary?fire blazes through present

Ethan Davis, 8th grade

my home is now the far past

I decide my future

Santa Rosa Middle School

II.

I have been a teaching artist with CalPoets for 18 years and live in Sebastopol in west Sonoma County, which was not directly affected by the fires, though our local high school was designated as an evacuation center. In the immediate aftermath, I spent time at a soup kitchen set up for evacuees there, but after a few days the number of volunteers exceeded the need, so I started looking for other ways to help. In the second week, when most schools were still closed and the air was still unsafe for outdoor play, a synagogue in south Santa Rosa, Shomrei Torah, decided to offer a safe and stimulating place for kids to be while their parents worked or dealt with the detritus of their lives. The day camp was welcoming volunteers. I packed up a satchel with some notebooks; our CalPoets lesson plan book, Poetry Crossing; colored and regular pencils; and a few picture books.

I was greeted at the camp by Katt, the young woman orienting volunteers and registering kids. “Most of them are pretty strong,” she told me. “Just keep your eyes out for some who may be looking a little lost.” I told her I might be able to write poetry with a few, and she suggested I work with any children who might be interested on the sofa in the lobby. I quickly found someone who did look lost: a first-grade boy wandering around with a large piece of Styrofoam packing material on his head. He was distressed because his lunchbox could not be found. Even though communal food was very plentiful, he couldn’t be tempted by anyone else’s apples, peanut butter sandwiches, or Capri Suns. But we made friends and he made it through the day, finally eating some birthday cake. Several times I took individual kids to the sofa in the lobby to take dictation of their stories and thoughts, and once the roles were reversed, when a little boy transcribed my words into the characters of his “secret baby language.”

When the schools reopened and I was due to restart my work in the classroom, I wasn’t sure how I would approach the subject of the fires in my poetry classes. I knew through Facebook that one of the teachers I regularly work with had lost her home. During this time, it was difficult making contact with people to work out plans, and the classroom teachers themselves had been back at school only for a few days. I had to go with my gut instinct in planning my lessons and ended up deciding to address what had happened to our community head on, but with lots of escape routes for those who weren’t ready to talk about their experiences.

A lesson I had used in previous years, based on Juan Felipe Herrera’s poem “Five Directions to My House,” seemed timely. Because the poem itself is somewhat surreal and because the lesson, created by Jackie Huss Hallerberg, gives the kids the opportunity to interpret the prompt very broadly, I felt it would be appropriate.

I arrived at Monroe Elementary School in Santa Rosa to learn that virtually all of the student body had been evacuated during the fires, though only a couple of kids in each of my classes had lost their homes. I told them how grateful I was to see them all safe, and to have the opportunity to use poetry at this time to share what was in our hearts and on our minds.

The student body at this school is 90 percent Latino, and they were eager to hear about Herrera, the first Latino US Poet Laureate. I shared his poem “Five Directions to My House,” which alludes to the kind of living arrangements he experienced as the child of migrant farmworkers. We talked about the freedom that one has in poetry and I encouraged them to choose whatever kind of “house” they wanted to—their grandparents’ house, a dream house, a place where they used to live, a place where they live now, or even their own body, the house to their soul or heart. I reminded them of the magical power of metaphor, which was the only lesson I’d taught earlier in this school year, the others having been cancelled due to the fires. I also asked them to take risks with their writing, pointing out how Herrera does this when he talks about an ant writing “with the grace of a governor.”

I often bring in vocabulary posters that help kids climb out of habitual ruts of language. For this class, I brought in posters with words related to colors, trees, animals, sounds, textures, flowers, construction, prepositions, times of day, and weather. Here are a couple of the poems that resulted:

Directions to My Home, My Heart

Go through the mystical creek that lets you feel your childhood memories.

Breyanna Wright

Listen to the trees say, “this way.”

Look through the spiny bushes that once had berries.

Look at the dangerous rose that left ashes behind.

Now open the unlocked, chained doors.

Now feel the hurricane winds.

Go left where this wolf will greet you.

There I’ll be standing in the forest to dance

and disappear in flames.

Gone

Erik Benitez

- A place where you used to run now is gone.

- Running in the grass to go to your house and now it’s gone.

- Ringing the bell and they say, “go away.”

- Going to your house to watch TV and now it’s gone.

- Playing with water in your tub, and now it’s gone.

- Then you remember your house, and now it’s gone forever.

Both Erik and Breyanna are sixth-graders in Nikki Winovich’s classroom at Monroe Elementary School in Santa Rosa, California.

III.

Since the period of time immediately after the fires, our team of poet-teachers has had a chance to refine our approaches. I noticed that I had trouble following directions in those first days back at school, and took this into account as I observed students experiencing a bit of shell shock. It has been particularly helpful to consult with a colleague who is both a poet-teacher and a marriage and family counselor. Perie Longo lives in Santa Barbara County, which recently experienced its own devastating wild fires. She emphasized the importance of creating a safe place for sharing and writing after such an event.

To this end, I made a special point of letting students know that they could write anonymously, if they wished. I asked that they put their names on their papers, but also to write “anonymous” on the page if they didn’t want to be acknowledged by name on future worksheets. I always want students to feel a complete sense of privacy between themselves and the page, but it seemed especially important under these circumstances. Once their poem is written, children often reverse this decision and choose to share it publicly after all.

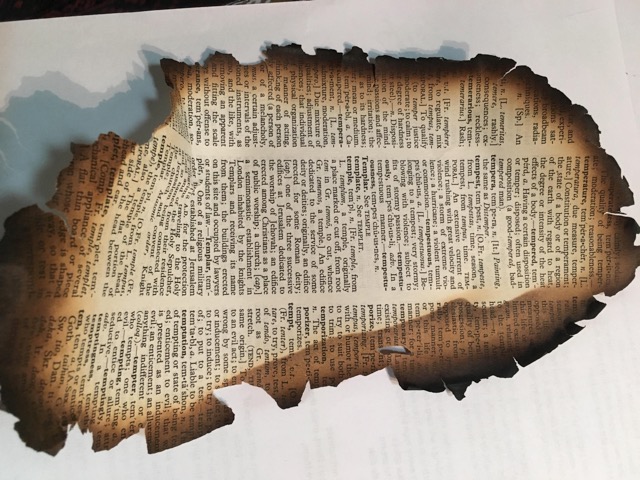

Longo also suggested inviting students to help create a list of “words that are important to you right now.” This access to each other’s words can allow students to pursue directions that might have previously been hidden to them. I tell students to look them over and pay attention to which words seem to be calling out, “Choose me.” Longo told me this activity was inspired by an experience she’d had several years ago at the time of another fire, when a janitor at her school presented her with a singed page from a dictionary he’d discovered and she felt how powerful it was to see these words that had survived the fire.

As a way to give kids some cover to say what they really need to say without writing directly about themselves, Longo recommended a lesson that teaches students how to personify feelings. There is a wonderful version of this lesson published by the Poetry Foundation, Square Toes and Icy Arms by Catherine Barnett. This version uses quotes from Zora Neale Hurston that personify emotions, aspects of the natural world, and concepts such as death, anger, havoc, fate, and courage.

Here are a few student poems by sixth-graders at James Monroe Elementary School in Santa Rosa that attest to the depth of feeling that can be evoked with this approach. Though these poets are not directly expressing concerns resulting from their proximity to devastating fires, their poems demonstrate the constellations of issues that young people may be going through.

Sadness

Sadness feels pain and suffering.

Josue Irra

He hides it in the daylight with a smile

but he cries every night.

He worries about a pet that he lost

and hopes will come back.

He fears that it will never come back.

He repeats his pet’s name over and over again

in his sleep. And when he’s asleep,

he dreams that his pet came back

and cries out tears of joy.

And when he wakes up, he notices

that it was just another dream.

His dream kept him alive from his suffering.

He wishes his pet would come back.

He misses his pet’s voice.

Mr. Persinger’s classroom

Depression

Depression is someone that not everyone knows.

Amy Arenal

Depression likes to be in a dark room in silence

with tears running down her face once again.

Depression puts on a fake smile when she is around people.

Depression’s eyes look red and swollen at night.

Depression doesn’t believe in friends because she would get back-stabbed.

Depression is related to Sadness and Anxiety.

Depression reminds me of a girl that once kept

all her feelings to herself.

She reminds me of the girl whose friends came and left.

She reminds me of the girl who used to self-harm.

That girl is me.

Nikki Winovich’s classroom

Sadness

Sadness is the person who will make you cry.

Erick Arango

He wears black jackets, black pants, black shirts and grey shoes.

His eyes are always watery and his hair all messed up.

Sadness is friends with Worry because they both make people sad.

Sadness likes to walk slowly with his head down, crying.

When he walks past people they ask, “What’s wrong?”

But he just keeps crying.

If Sadness enters your heart, he turns it dark and quiet.

He travels by foot in the rain.

His only relative is Loneliness.

He dreams about stopping being sad, and being happy,

but he can’t be happy because he has been traumatized

Nikki Winovich’s classroom

One other lesson Longo suggested for working with children after a community trauma was writing “question poems.” She said that this exercise had grown out of a particular experience in her hospice work when she was asked to come to a school where a student and her father had been killed in a plane crash.

“I gave the students some of Neruda’s questions from his Book of Questions,” Longo said, “and talked about death as one of the great mysteries, as is sudden disappearance of any kind. I acknowledged that often there are no answers to the questions we have, and asked them to just write the questions. I also told them that a wise man once said, ‘Really good questions have no answers’.” Longo said the poems the students wrote in response to this exercise uncovered every aspect of their grief and sadness.

One of Neruda’s questions that Longo shared with her students was, “Is there anything in the world sadder/ Than a train standing in the rain?” She used this with her students as a model for their own questions, prompting them to replace “sadder than” with “Is anything more lonely than,” or with other emotions.

IV.

This year’s devastating wine country fire season is over. I’m reminded, though, that part of the function of poetry is to lift the veil of ordinariness that often covers our daily lives, allowing us to see and heal more deeply. A breakthrough by any student in the class can give permission to many more to share their feelings. I still see evidence of the distress and confusion, as well as the awe and wonder, that students, freed by poetry, are able to express. I’ll end with a two-line question from a group poem by some of Longo’s students. Though it was written on a different occasion, it sticks with me as a haunting echo of what young people experienced during the ruinous Sonoma County fires of 2017.

Why is the world here today when

wind is howling like a ghost?

Photo (top) Credit Barbara Hirschfeld

Phyllis Meshulam is a poet, teacher, and coordinator for California Poets in the Schools and Poetry Out Loud. Her work has appeared in Earth's Daughters, Natural Bridge, and Tikkun, as well as in the award-winning anthology Veterans of War, Veterans of Peace. She will be presenting at the 2016 AWP Conference and at the Split This Rock conference in April 2016.