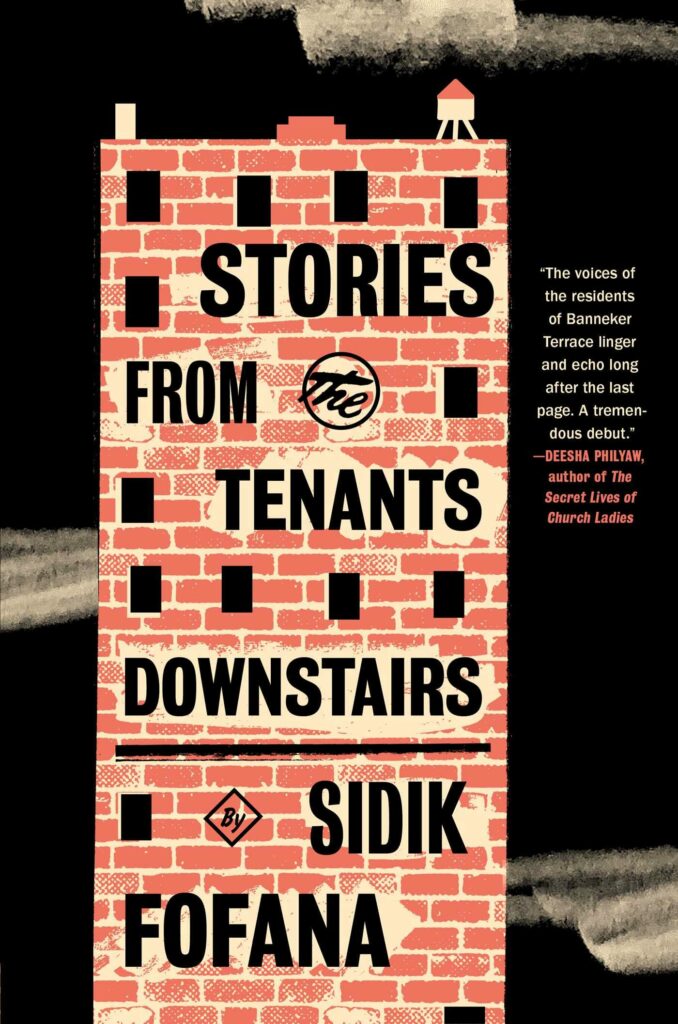

Sidik Fofana is an English teacher at a public high school in Brooklyn. He earned his MFA from New York University, he has fiction published in Granta and The Sewanee Review, and he received an Emerging Writer Fellowship from the Center for Fiction. His debut book, Stories from The Tenants Downstairs, will be published by Scribner on August 16th, 2022.

Alex Weilhammer spoke with Sidik Fofana twice over the phone, on January 6th and January 13th.

Alex Weilhammer (AW): In your interview with Adam Ross in The Sewanee Review, you spoke about your relationship with Lori Moore when you were getting your MFA from NYU. This clearly was an important mentor-mentee relationship for you. Could you speak to your own experience as a mentor in your teaching role and to the importance of having thoughtful, compassionate teachers more generally?

Sidik Fofana (SF): It’s important to have people in your corner, people who encourage you, and most importantly people who see something in you, for you. One thing I like about high school, you can be that person as a teacher. It helps a student’s life in tangible ways. You know, to have the honor of writing someone’s college recommendation. You can’t erase that. That’s something they remember. As an English teacher, being the first person to introduce them to a text, to praise them when they analyze a text in a certain way, it’s just a grand feeling. There’s an inherent loneliness you have as a student because you are in a classroom and you outnumber the teacher. It’s hard to get that individual attention, so when a teacher singles you out and says you’re special and you have potential, even if it doesn’t seem true to you, it kind of motivates you and gives you an energy. I think that’s the special power that a teacher, educator, mentor can have, and sometimes we overlook that.

AW: How long have you been teaching, and how would your students describe you as a teacher?

SF: I’ve been teaching since 2007—since right before Obama was elected. My students would describe me as kind of strict, someone who sweats the small stuff, somebody who is constantly getting on them for being in uniform. Someone who does strategic seating, an enforcer of the rules, and somebody who likes structure. I also would hope that my students simply describe me as someone who really cares. Even on the day when I’m really lecturing someone or really reinforcing the non-negotiables of the class, I hope they’d say it comes from a place of love. I hope they would say that I’m consistent, never miss a day, and like clockwork, I’m predictable in the most reassuring ways. I’d also hope they say that I love books, in that I’d prefer a book over a movie or TV show. I’m a pretty strict and traditional teacher. I throw in some fun things, some fun activities, but most of the time, it’s like, “You’re going to write an essay, you’re going to be drilled.” But I hope they understand and appreciate the place that that’s coming from.

AW: How did your teacher voice develop over time? Were you always the enforcer?

SF: I was definitely the cool guy when I started. I was 24, and I’d come in with security guards, and they’d be like, “Do you go to school here?” I had cornrows; those were really popular at the time of Allen Iverson. I played basketball with the basketball team. Definitely wore a durag, definitely listened to the same music. Cracked jokes. My first year, I was 24 years old, and I worked at a transfer school. A lot of the kids were like 17-18 and the oldest were 20-21. A lot of them were close to my age. There’s a natural evolution there, and it happened with me in that I became more of a person who, from experience, learned that kids need that structure. I became more and more focused on the rules; it just happens from experience.

The pro to being “the friendly teacher” is that kids see themselves in you, they confide in you, and they are a little more themselves around you. But inevitably they take it a little too far. They push, and they try to see what can be taken advantage of. You evolve and become that person who’s a little more serious and a little more authoritative. As a first-year teacher, you’re like, “Ew, I don’t want to be that person.” But when you become that person, you’re like, “Kids appreciate that too.” They want you to be their friend, but they secretly respect you more sometimes when you give them that professional distance.

AW: How does your teaching influence your writing life, and in what ways is your teaching distinct from your writing practice?

SF: In terms of content, a lot of the demographics and population that I have been writing about is pretty much the same demographic of the students that I teach. When I’m teaching, it feels like I’m in an authentic place. It feels like I’m inspired; it feels like I’m a monk. The teaching reinforces the simplicity of writing. The more complex you get as a writer, you still go back to the same elemental things. A great story is always going to have characters, plot. The same things you teach kids in high school for the first time, you have to focus on as a writer. That’s one of the advantages of teaching younger kids because you’re closer to the foundation of what makes good writing. The fact that I’m teaching figurative language from the start: “What is a metaphor? What is a simile? What is conflict? How does a story develop? What is a hero? What is a protagonist?” I’m thinking about these for five periods a day. I can think of no greater training.

AW: As you wrote your book, how did you set out to make time for your writing while also ensuring you took care of your teaching responsibilities? Do you have a set of guiding principles you follow, or are you more of a go-with-the-flow type of person?

SF: It’s hard to be a public school teacher and write. It’s one of those things where you have to constantly guard your time. I might set aside 45 minutes and the whole time I’m thinking about lessons I’m planning or other bureaucratic things I have to do. When I was first writing Stories from the Tenants Downstairs, I would be lucky to get 45 minutes. A lot of the word counts for the day were like 50 words, 100 words. The most was like 343 in a day. I’d get discouraged because I’d hear of writers getting 500-1000 words, or people writing four hours a day.

You just have to protect your time. The one thing I was consistent with was writing every day. That constant thinking about it, even if it was for a short time, helped me parse out the novel in my head. I think the amount of time you write per day doesn’t really matter. I always look to heroes like Grace Paley who wrote on napkins while she was making dinner. Writing doesn’t always have to be at the desk. Especially as a New York City teacher, you have to take what you can get.

AW: Many aspiring writers find themselves in education as a way to pay the bills as they write. What advice do you have for young writers who enter the classroom?

SF: Try to put your best effort into education and into your job. Especially with teaching books, the creativity that you can put into it, it will help you with your writing. A lot of young writers kind of see teaching as a part time thing until they have enough to sustain themselves with writing, but very few people sustain themselves with just writing. For me, being just a full-time writer, the prospect of that is actually kind of boring. I know those are fighting words for people who do that, and I respect it. It’s not like I look down on people who just write all day. Even when you are really dedicated, it rarely takes a whole day. There are very few people writing eight hours a day.

Teaching is a way of thinking through writing problems. If you teach and you do it well, you are learning yourself.

I’ve never understood how some people could really put their all into writing and take teaching as a side thing. If you are a writer who concentrates and really wants to make something great, it seems like it’s your default mindset and you’d want to do that in other facets of your life. I would honestly say, never aim to be a full-time writer. Even full-time writers are good because of what they’ve experienced and what they’ve read. Even financially. If you get a lot of money from it, the money is always slow coming. Then, if you are relying on that money to live, it kind of taints the way you write. You’re more likely to send off something that’s not done. You’re more likely to accept an assignment that you wouldn’t accept. To me, “Don’t quit your day job” means don’t rely on writing as your sole bread and butter because when finances get into the picture, it really colors and influences, sometimes not in the best way, the decisions you make in the creative process. Be the best at your full-time job, and you’ll be the best at your writing.

AW: Writing a first book is something, by definition, one’s never done before, and the writer can oscillate drastically between excited inspiration and pure dread throughout the writing and editing process. How did you navigate this process, and in general, what advice do you have for writers as they are struggling through their first book?

SF: There’s something in my mind that I call the absurdity of failure and the absurdity of success. The absurdity of failure is that you could be doing something decent. There are stories that people are working on right now that are going to go on to be published in The New Yorker. The time between a project being finished and the validation is so long. Sometimes it seems like it’s never going to happen, and it’s completely absurd. On the other hand, when things do happen, you get hailed as some kind of expert when you feel very insecure, and you still feel unsure of your abilities, and even when those abilities do manifest themselves, they are inconsistent, and you have to talk about the writing life from a point of view of mastery when it’s not the case. That is absurd as well. You get to the point where you have success, and it’s because you didn’t listen to constant criticism or constant praise. When you hear the praise that you’ve been dying to hear, it comes over your scabbed heart and you can’t even enjoy it. That is the absurdity of success. To young writers, I go, “It sucks. Be prepared. Don’t let either absurdity discourage you from writing.”

AW: In “The Young Entrepreneurs of Miss Bristol’s Front Porch,” published by Granta, you employ a colloquial narrative style that’s quintessential New York. Can you speak about the composition process that went into representing this style on the page?

SF: That story was inspired by my first year teaching and having an all-girls class of freshmen and imitating the way they talked and thinking about how to portray that on the page. I found that the vast majority of the words are standard English. In my head, it sounds so distinct and like a totally different style of English, but the vast majority of words are standard, and it has to do with syntactical changes, and the push-pull with that is: How do I make it sound like the dialect, and how do I not overdo it?

A word like “trying to” I presented as “tryna,” and that would hopefully signal to the reader, without making every single word phonetic, that this was how they spoke and how it sounds. Certain words like “grandmuhva” and spelling that out phonetically. Making those phonetic choices in the minority, but just enough to conjure up a voice in the reader’s head. As I wrote that story, I had students in my head, and it wasn’t necessarily about the phrases, it was about the sassiness, the inadvertent insights. It’s inadvertent honesty, but it ends up being insightful. And it’s girls who are 14 and 15, and they’re naive. My biggest takeaway about writing a story like that is that at first I thought it was about the words, the word choice, the phrases. Really, it’s about specific words and getting tonally accurate, and it’s about the naivety of the characters more so than it is trying to spell out every word phonetically.

AW: Who do you want to read Stories from the Tenants Downstairs, and what do you hope they take away after reading it?

SF: Anyone who is interested in books and anyone who is not interested in books. I hope they can be caught by a line or phrase or open to a random page and have an arresting voice pop out at them. I also like the idea of someone who hasn’t had that experience or grown up in cities or interacted with people of color to pick up that book and still connect with the human elements. I like that idea of someone in the middle of America who just happens to pick up the book and was like, “These characters are not like me, but I can still understand their story.” I think of all the times I’ve read a book set in the 18th century or that took place on the prairie, and as someone who grew up in the city and as a young person of color, being that and still being enthralled, fully riveted by these stories. I love that idea about a human who reads about a human that’s totally different from them and still finds that connectivity. Anybody that has an open mind enough to just give it a try is my ideal reader.

Alex Weilhammer is a high school English teacher in Harlem originally from Indianapolis, IN. A graduate of DePauw University and The New School, he has published articles in Sarasota Herald-Tribune and The Indianapolis Star and fiction in Stat(o)rec.