In the final workshop of my graduate program, I was called out in class by Fanny Howe. She called me out for acting in a way that had always won me praise. It’s taken 20 years, but I think I’m ready to learn what she was teaching me.

The first time I ever saw Fanny, she was seated at the head of the classroom table with my friends from my cohort filling in the seats around her. We had been buzzing about this chance to study with her, and here she was. None of us could have known exactly how rare the opportunity was. Our workshop would be both the first and the last that she taught at our university.

As she sat with us in a loose blue-gray sweater and jeans, a backpack crumpled next to her, and her mostly gray hair pulled back in a plastic clip, she had the dual presence of a wise elder and a drop-out somehow back to teach the class.

Readers of her essays know that she’s existed on the outside of almost every system she’s encountered—the upper-class Cambridge world of her childhood, the institution of marriage as a young mother, the credentialed echelons of academia as she was rejected from college when she first applied. Her early books were written under a pen name. Motherhood has maybe been the only cultural identity she’s wholeheartedly inhabited.

Sitting with one arm on the table, but with her body curved away from it, her posture made her slight frame smaller. But there was also something large-scale about her. Her stature in contemporary poetry and her formidable spiritual presence were palpable.

In the final workshop of my graduate program, I was called out in class by Fanny Howe…. It’s taken 20 years, but I think I’m ready to learn what she was teaching me.

Fanny taught by welcoming us into her sense of what it means to be a poet. She cultivated comradery and productivity, laughing a lot, a gravelly delighted laugh, as she kept discussions focused and moving forward. She gave us weekly prompts that were open, there was no right way to approach them. She introduced us to the post-WWII avant-garde that had been crucial to her development. Fanny prompted us to think collectively and individually, asking us what we wanted from our generation of writers and assigning us to draft individual statements of poetics. From the first class she treated us like we were real poets, charged with discovering what our era of poetry could mean, and her trust in us demanded that we take our work seriously.

One reason I wanted to study with Fanny was my admiration for the moral seriousness of her writing. This was the fall of 2003. New York City was still absorbing the shock of 9/11. Former President Bush had just expanded his administration’s “War on Terror” to begin The Iraq War. I had joined thousands of others in marches to protest this expanding violence. I came to graduate school in New York for many reasons, all of them unrealistic for someone with no money and few professional skills. I was on the run, in a sense, from a floundering first attempt at adulthood in the Midwest. I wanted to commit to an artistic path, but knew I needed some examples to study up close. And I wanted to stop the war. Fanny was the first workshop teacher I’d had who I fully trusted to help me think about how poetry and political resistance might intersect.

The moment in her class that impacted me above all the others, though, was quick, procedural. It was about half-way through the semester. We were all asked to read a response to a prompt from the week before. Everyone had shared but me. As each of my peers read, I wondered when it would be my turn. My face got redder after each reader as I performed my interest in their work but wondered what they’d think of mine. OK, anyone else? Fanny asked. I hadn’t read. Don’t my friends wonder what I wrote? But I wasn’t going to speak up. I didn’t want to be selfish. Silently, I willed someone to notice.

Not demanding attention was something I understood to be noble, something teachers had always praised me for. It was the very thing that underpinned my identity as a good student. Of course, there was a shadow side of this passivity. My contorted ambition emitted static.

Fanny was the first workshop teacher I’d had who I fully trusted to help me think about how poetry and political resistance might intersect.

We moved on to a conversation about that week’s reading when someone in class spoke out: Laura didn’t read her piece! Fanny looked at me. Do you have it? I said that I did. Why didn’t you tell us? I answered something like, Um, it’s not a big deal. In that instant, I felt Fanny see into my mind, the interior I thought I could hide and present as I liked. She looked right into me and said something like, You’ve done this before, are you aware of that? I was confused and shook my head no. You’re waiting on your classmates to step in on your behalf. You can just be direct. I froze. I felt exposed. I think I began to sweat through my shirt. Though the gears of my mind could barely turn, I did recognize that Fanny was exactly right. I had been totally unaware of this tendency to hide myself while simultaneously hoping, even expecting, to be found. I caught my breath. She looked at me encouragingly. And then I took my turn.

What do we owe each other when we come together as writers? Writing workshops can be crucibles for developing writing, but also for developing emotional intelligence, social awareness. Our defensiveness, evasion, shame, pride, all the human responses to sharing and critiquing new work inevitably emerge. At that point in my life as a student I had the basic workshop etiquette down. But what Fanny was asking of me was deeper, more individualized, more complex.

You can just be direct. She was articulating the central challenge in my life. What if having this impediment, my reticence, revealed, allowed me to change on the spot? Of course, it didn’t. Fanny’s observation shook me, and I put it away for 20 years. But I think I’m ready to accept this gift from my teacher. Now I feel the gleaming heat of it. My embarrassment is gone. Can I change my life?

As Fanny led us through the semester, delighting in poems with us and probing as we articulated new ideas, she was always alert to our dynamics with each other. I remember that she brought attention to a conversational impulse that was the opposite of mine. A classmate who spoke up confidently, even ebulliently, was asked to take care that his enthusiasm didn’t obfuscate his ideas. Fanny made us aware of our tendencies. I think this is connected to her thinking about the danger of obliviousness and its even more damaging related trait, self-deception.

As the conversation about pedagogy evolves, Fanny’s ethos feels relevant. In an interview with Fiona Alison Duncan from 2020, Fanny spoke about self-deception, privilege, and race, charging that “Whiteness now has the pallor of cowardice.” Writing workshops can be a place to develop courage. This structure, if used with sensitivity, can help us all develop the awareness we need to pivot to new approaches in our writing, thinking, and interactions.

My classmates still think about moments of Fanny seeing into them. In a recent exchange, I caught up with Justin Marks, who remembered that Fanny told him in a meeting that his life’s subject was failure. And it was! he said. It was very validating and gave me something to hang onto for years. Another suggestion of hers didn’t help until later. In our class, Justin brought in a poem that used a lot of scientific language. Fanny suggested he scatter the scientific words throughout his poems. I kind of dismissed the idea at the time, but all these years later that has become a lot of what I do—take language from science or other specialized disciplines and collage it into poems where it feels like that language fits. I also caught up with Wende Crow, who remembered that Fanny was the first person to recognize the serious depression she was obfuscating in her poems, which was a comfort. She articulated exactly what I was doing when I couldn’t articulate it at all, Wende said. Then she got swept up in my joy with me when she was advising my thesis. . . . We laughed a lot. There were also less consequential but still potent examples of Fanny’s incredible perception. Once, she read my mind casually in class discussion without making a scene of it. I was thinking of an apple and trying to formulate how it connected to conversation. Fanny called on me, saying, Yes! Laura! Please tell us about the apple.

It was unnerving knowing there was no hiding from her. During an office hours meeting, as we discussed one of my poems, a poem I thought I had written from the perspective of a pilot in World War I, Fanny said, You’re always writing about your life, right? At the time I was embarrassed. Confessionalism and sincerity in poetry were not in vogue. And I wanted to be inventive and intellectual in my poems. I wanted to avoid the cliché of writing about myself. In her own poems, Fanny writes philosophically, but with warmth, avoiding autobiography. I try not to drag my furniture in, she said in reading at La Jolla in San Diego. But when studying her vast body of work, I see that it is filled with her experience. A few weeks after that meeting I began to realize that Fanny wasn’t chiding me. It was through accepting my drive to write about my life that I have ultimately been able to take on subjects like politics and gender that were important to me. Fanny was telling me, again, that it is OK to accept who I am, and it’s OK to be direct.

Fanny was teaching us not to wait to begin participating in poetry.

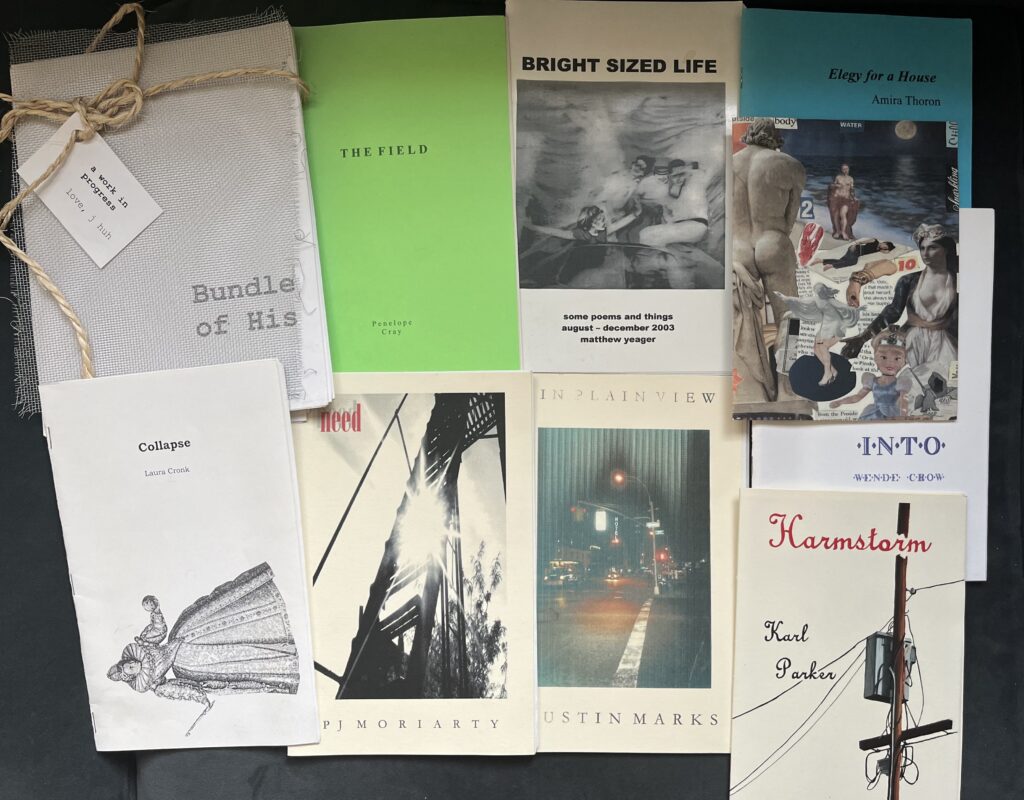

By the end of that workshop, we felt a collective giddiness at having seen everyone in the group grow so dramatically. She encouraged each of us to commit more fully to our own sensibilities and the outcome was stunning. Our final project was to not only compile a chapbook-length series of poems, but also to produce enough copies to give as gifts to everyone in the class. Fanny was teaching us not to wait to begin participating in poetry. I’ve kept that set near me through every move in the intervening years, a talisman of artistic luck.

Fanny announced at the end of one of our final sessions that she wouldn’t be back, wouldn’t teach again at our school. She told us that our class was just too good, she didn’t want to be disappointed the next time. After she said it, she smiled and laughed a little. I love that laugh! We, her students, felt proud of ourselves and believed her. Looking back into the past, which as Fanny said, is the future viewed from another direction, I see us as we were then, so perfectly her students.

Though the experience of studying with Fanny was formative, I haven’t tried to directly emulate her style of teaching. I couldn’t even if I wanted to. She brought what seemed like her whole self to us—her influences, her identity as a woman and a mother, her experience of artistic community, and her incredible perception. She used that perception to directly, but not unkindly, challenge each of us to be our whole selves. She wanted us to be capable and self-aware so that we could do the work we came to do, but also avoid hurting ourselves or each other in the process. I have my methods for steering writing students toward the same goals, but I use my strengths, which are different from hers.

Several years after that class, I saw Fanny in the lobby of The New School about to attend a reading. We happily greeted each other and as we caught up, she asked me if I was writing. Not much, I said. I had a new baby and a job. It was hard to fit writing in. What she said next, I never could have anticipated. Well, she said, you just have to lower your standards. The elevator door closed, and I rose up five floors, stunned. I should lower my standards, I thought. I’m still writing all these years later, precisely because I have.

Featured photo by Tobi on Unsplash.

Laura Cronk

Laura Cronk is the author of Ghost Hour and Having Been an Accomplice from Persea Books. Her poetry and nonfiction have appeared in Court Green, Iterant, The Literary Review, Lit Hub, the Best American Poetry series, and other publications and anthologies. She is an associate editor at Tupelo Quarterly and is an assistant professor of writing at The New School.