Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick. Although we all prefer to use the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.

—Susan Sontag, Illness as Metaphor

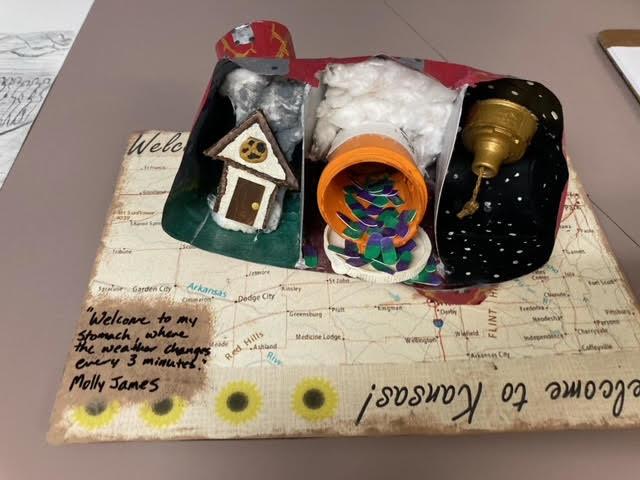

One student brings in a sculpture of two people embracing. It is wrapped in broken string, tangles of tape, and drips of hot glue. I don’t know yet how this will relate to the central metaphor in her life story assignment, but I have a guess. One student brings in a teddy bear crocheted with scraps of yarn. It is missing an arm. One student holds up a clay hand with a green ribbon tied around the pointer finger and explains: “My fear is my own memory. I’m afraid I’ll forget important things and let people down.”

The students, undergraduates in my Life Stories class, have brought in these objects as part of an assignment in response to our reading of cartoonist Lynda Barry’s book, One! Hundred! Demons!. In the book, which the author says was inspired by a 16th-century Zen monk’s painting of 100 demons chasing each other across a long scroll, Barry depicts the “demons” of her own life, “the moments that haunt you, form you, and stay with you.” I’d asked my students to craft an object to serve as a metaphor for the “demons” in their lives. In class, we take time to talk about the meaning of each object, what part of the student’s life story it is drawn from, and how they plan to deal with the fear the object represents.

Those who take my Life Stories class are often not eager creative writers. They are biology majors and health sciences majors who are looking to satisfy an English requirement, and so ended up in my class, a creative nonfiction course specifically for pre-med students. As an English professor, I think all texts have the power to connect to our lives, but I always take care to choose readings for the course that speak to a variety of health conditions so that no matter what branch of medicine these students are going into, they can find a connection to the work and see how the texts are relevant to them. As the course progresses, many students find that the essays, memoirs, and comics we read speak not just to their future career plans, but to their own health concerns—or those of their families—as well.

Those who take my Life Stories class are often not eager creative writers. They are biology majors and health sciences majors who are looking to satisfy an English requirement . . .

All the reading, writing, and creative activities in the course are focused on the body. We read excerpts of Roxane Gay’s Hunger and Maya Angelou’s cookbooks, and students swap recipes with each other and write micro memoirs about food and culture, and sometimes connect their traumas back to food the way Gay and Angelou do. We read David Small’s comic memoir Stitches, studying the way his panel transitions control both narrative time and emotional scale, and I invite the students to draw some panels of their own, keeping in mind the ways in which emotion and/or illness can affect perceptions of time and scale.

In each reading, we talk about the course’s four key questions:

- What metaphors do authors use to address illness and trauma in their writing? How do these metaphors reflect questions of pain and/or identity.

- How do authors speak about the body?

- How does illness affect narrative time? How does the order or disorder of a narrative speak to the physical and/or emotional upheaval of illness?

- What is the patient-care provider relationship in the story, and how is power negotiated in that dynamic?

The nonfiction writers we read will often disrupt a linear sense of time in their work in order to organize the narrative climax around meaning rather than action. In the memoir When Breath Becomes Air, for example, we know from the prologue that the author dies in the end, so we know the story is not a narrative of overcoming illness. Instead, as the students observe, the narrative is structured around the author’s relationships as he is living and dying. We see similar creative approaches to narrative structure in our other class readings as well, whether they deal with loss, chronic illness, processing trauma, or living with mental illness.

My students learn how metaphors can increase reader empathy because they make pain visible and easier to connect to. They observe how imagination can be something that the author takes refuge in as a way to heal, but also how sometimes the imagination can be the site of more suffering. Both the solace of imagination and its terrors, for instance, are made very clear in the graphic novel Stitches. I love getting these reluctant biology and health science majors to talk about the nuances and complexity in the narratives we read. They are often students who excel in memorization and the application of techniques, but critical analysis can be a more challenging intellectual territory for them.

My students learn how metaphors can increase reader empathy because they make pain visible and easier to connect to.

The capstone project for the course calls for students to write their own life story, inspired by one of our class readings. Quite a few choose to write cookbooks based on Maya Angelou’s, connecting recipes to important moments in their lives. Sometimes students emulate Susanna Kaysen’s Girl, Interrupted and Emilia Phillips’s “Excisions” and include their own medical documents as part of their storytelling. I’ve also had students include police reports and death certificates in their personal narratives to create tension between the stark language of medical reports (and other formal documents) and their own words for their experiences. Some create comics about assault or eating disorders that speak to the themes within David Small’s Stitches and how sometimes people seek out other ways of “speaking” when they feel unheard.

No student is required to write about trauma. In fact, we discuss the importance of not opening wounds for a class assignment and making sure that if they are thinking about tackling difficult emotional subject matter that they have the other support systems in place. I offer examples of students making orthodontia cookbooks and all the soft foods they ate in their braces years, and a daredevil’s guide on what NOT to do if you want to have good knees as you age. There are many ways for these students who plan to go into health fields to write about their own physical and mental health and make it playful, funny, and even cathartic without having to write about their most painful memories. However, many still choose to write about difficult experiences with suffering and loss, using the opportunity of this course and its assignments to find language for challenging things in their lives.

I work to ensure the emotional wellbeing of students during the course by talking to them early on in the semester about the Pennebaker studies, which make a strong case for the physical and psychological benefits of automatic writing for a few minutes a day a few times a week. Since they are students heading into medical careers, I always hope these studies and statistics are extra persuasive, and I suggest making their life story a journal or diary about the first semester at college. It’s my hope that as well as helping students process their current concerns, a writing practice like this might even build a habit that will benefit them beyond class.

This past semester while preparing for teaching evaluations, my students and I had a class conversation about what surprised them about the class, what was hardest, and what readings they felt were most helpful to them. When I asked what was hardest, one student quickly raised their hand and said: “The life story. But it was the most rewarding, too.” Other students nodded and started talking about how helpful it was to get some of the things they’d bottled up out on paper.

In her life story, the student who brought in the clay hand and talked about her fear of forgetting wrote about the memories she wishes she could forget. The student who brought in a crocheted one armed bear made from yarn scraps wrote about disordered eating and how she’s worked to recover from the idea of trying to conform to a picture of a perfect body. The student who brought in the embracing sculpture covered in messy and fractured ways of connecting (broken string, tangled tape, messy glue) told us about her fears of abandonment. In her life story, she wrote down the recipe she made one night when her father yelled at her mother and told her what a terrible cook she was, not knowing it was she, a child, who’d tried to express love for her family by cooking dinner. Other students shared their fears about failure, anxiety, and genetic conditions.

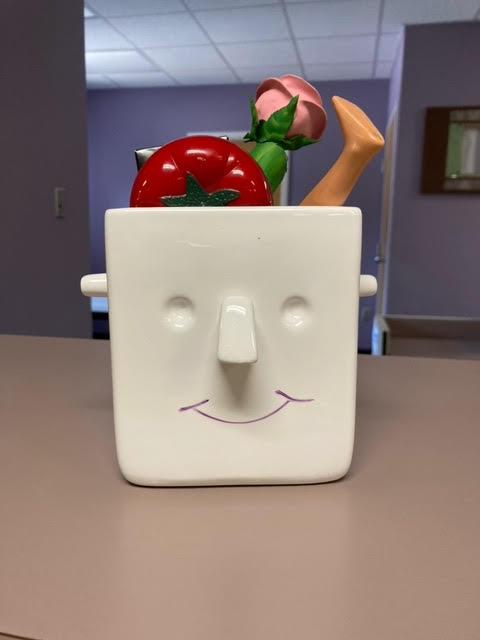

At the end of the semester, I was honored when some students gave their metaphor projects to me. I often put student projects up on the walls and shelves of my office. It has become a museum of fears that have been named and given shape. I never want to forget the importance of those days in the classroom, and I want every student who comes to my office to know their life story has been witnessed.

Featured photo by Tara Winstead.

Traci Brimhall

Traci Brimhall is the author of five collections of poetry. Her work has been published in The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Nation, The New Republic, and Best American Poetry. She’s received creative writing fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Parks Service. She teaches writing workshops and medical humanities at Kansas State University. She is the current Poet Laureate for the State of Kansas.