Spring had arrived, April was around the corner, and National Poetry Month was about to begin. I loved opening the mail each year to find the poster sent to teachers announcing the annual celebration. That year’s poster featured a line by Ada Limón from her poem “The Carrying”:

. . . we were all meant for something.

It was 2023, and I was teaching Spanish to high school students at Léman Manhattan Preparatory School in New York City. I had arrived in New York only two years earlier after a longer than expected stay in northwestern Argentina where my home is. I’d been unable to leave San Miguel de Tucumán when the borders closed at the start of the pandemic, and I still felt a sense of amazement to be teaching in a classroom where my students and I could see the sun setting behind the Statue of Liberty. It was important to me that my students bring that asombro—that “sense of wonder”—to their learning of a foreign language, and one of the ways we made that happen was through creative writing.

It was important to me that my students bring that asombro—that “sense of wonder”—to their learning of a foreign language, and one of the ways we made that happen was through creative writing.

Mis Antepasados / My Ancestors

I introduced the Mis Antepasados / My Ancestors writing project to my ninth and 10th grade Spanish I class just before spring break that year, so that students might have time to develop their thoughts and words over vacation week. On the white board I wrote:

Mis Antepasados / My Ancestors Final Project

Write a poem to an ancestor.

- Who is the antepasado you will address?

¿Quién es?- Where do they live? Which country or territory?

¿Dónde vive?- Choose an object that is important to your ancestor. What is it?

¿Qué objeto es importante para tu Antepasado?- Ask questions. Use verbs in the present tense.

My instructions to the class were brief and direct, without too much explanation. I wanted the assignment to feel like a leap to them, just as poetry did. I didn’t know if my assignment would work, if students would be excited enough to run with it, but I had set up a culture of creative writing in my beginning Spanish classes from the start of the year, so my students were used to unusual assignments.

In our first class after the break, students brought in the name of an ancestor. I handed out blank sheets of paper so that they might begin a dialogue with their ancestor on the page. Most of the students felt lost. They thought they did not know enough Spanish to create a poem. I spent time with each student individually, modeling the kind of questions I might ask the student’s ancestor. Once the students had their first questions, I told them to use their imagination to answer it. This was usually enough to get them started.

Along the way I helped them with their language questions. Every time a student asked ¿como se dice? I would answer, saying the word they were looking for aloud and writing it on the white board. Soon the board was filled with new Spanish words that all students could use as they worked on their projects. I used different colored markers when I wrote these vocabulary words—sky blue, green, pink—so that together, all the words the students requested made a kind of rainbow on the whiteboard, highlighting the shared nature of creativity. New Spanish vocabulary spun out of every class. Because the students were using this new vocabulary in the moment to help them convey their thoughts on paper, the words had weight. They were real to them.

Because the students were using this new vocabulary in the moment to help them convey their thoughts on paper, the words had weight. They were real to them.

I also brought in a large box of colored pencils and set it on a desk in the front of the room for the students, so that they, too, could use color to illustrate and bring life to their projects.

Not all students were open to the idea of writing to an ancestor. But Señora, I don’t know who my ancestor is. I don’t know what object was important to her. I don’t know where my ancestors were born. I do not want to read my poem aloud to anyone. I do not want to illustrate my work. Don’t force me. I had to be very patient with these waves of nos. I did find that when I shared the Mi Antepasado project during parent teacher conferences, many parents responded with real excitement, and their enthusiasm helped to inspire their children.

In the end all the students participated. One student created a wonderful poem comprised of 11 questions written in a playful tone, because he said that he did not have the faintest idea who his ancestors were. It began: Hola los antepasados en el viejo Australia! / Hello ancestors in old Australia! Another student wrote to her country of origin, Ghana, as her ancestor: Hola, / ¿Cómo está Ghana? / ¿Cómo es la vida? / ¿Cómo se hace la tela Kenti? And another wrote a poem in the form of a letter to her ancestors, asking them if they had been forced to learn French because they had been colonized.

The countries of origin for the students’ ancestors included Denmark, Brazil, Ghana, Poland, Hungary, Italy, Guatemala, France, Greece, Albania, and Russia. We worked during our class period, and the students were also permitted to take work home. I asked that their poems be organic, that they not write a poem in English and then press a button to have it magically translated into Spanish. When I received the final poems, most of them handwritten with their illustrations, I felt such gratitude and joy at the imagination the students brought to their work.

Art and Poetry Collaborations

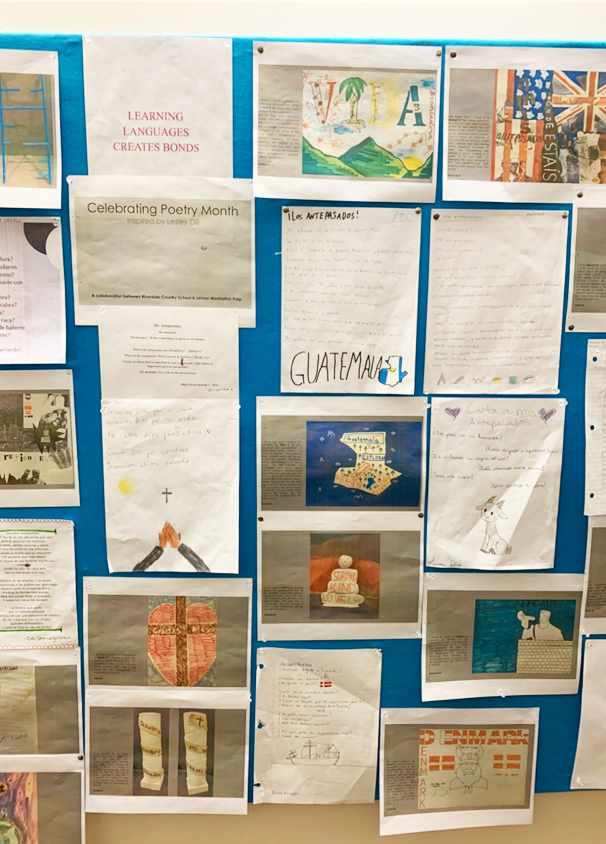

When the poems were completed, I contacted a colleague of mine, the artist Narges Anvar, middle and upper school visual arts instructor and director of College Arts at Riverdale Country School, to see if she would be interested in having her ninth grade art students create work inspired by the poems. She agreed and assigned her students the project of working with the poems, which I had scanned and sent as PDF documents, to create drawings and sculptures in the fashion of American artist Lesley Dill. Narges had chosen Lesley Dill because Dill works at the intersection of language and fine arts, often using words from poets in her art pieces.

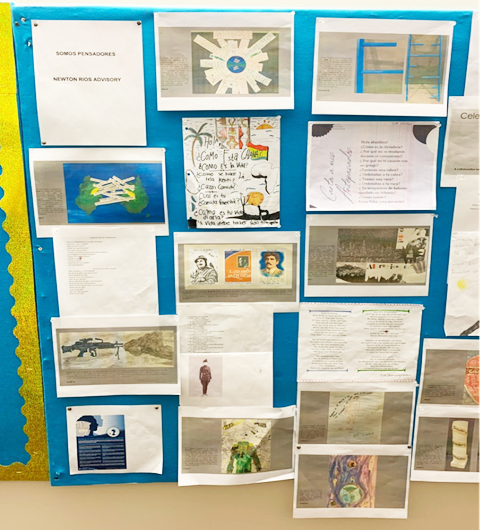

Each Riverdale art student had to choose a Spanish word or a line from one student’s poem to work with. On a Zoom call at the end of April, the Riverdale art students revealed their creations to my students on the screen projected on the white board. My students were amazed by the artwork, touched by the thought that had gone into each collaboration, and proud to have the collaborations displayed on a school bulletin board outside of our classroom.

Making Language Come Alive

At the end of that school year, I took the class on a field trip to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) to see two exhibits: Georgia O’Keeffe: To See Takes Time and Chosen Memories: Contemporary Latin American Art from the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Gift and Beyond. The students were finally learning the past tense, and I wanted them to feel all that was possible now that they could describe events in the past as well as the present.

I did not know, when we started out, how well my students would respond to the Mis Antepasados / My Ancestors project and where it would lead. But each day when I greeted them—Buenos días clase. ¿Cómo están?—I could see in their faces how eager they were for inspiration, and this project was able to tap into their lives in a way that had meaning for them.

A language classroom should be a place where the language being taught comes alive. I want to bring the lived experience of each student into my classroom, charging the words they are learning with life, cobrándoles vida. This takes time. It takes nurturing and care. But if done right, learning a new language can offer us not just new words, but new ways of seeing and knowing.

Featured photo by Carolina Contreras.

Alexandra Newton Rios

Alexandra Newton Ríosis a bilingual Latinx poet, translator, and professor. Born in Manhattan, she has recently been living in the small city of San Miguel de Tucumán, Argentina. She received an MFA in English from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and an MFA in Translation in Comparative Literature and a BA from Sarah Lawrence College. She is a graduate of The Chapin School in New York City. In 2004, 2009, and 2010, she was invited by the American Embassy to participate in the Buenos Aires International Book Fair. She is the author of Cielo. Cielo. Cielo., The Grace Poems/Poemas de la gracia,andAmaicha: Language Lost and Found, all published in bilingual editions by Ediciones Magna in Argentina. She turned to creative nonfiction withThe Light of Argentina: A Philosophy Diary Conversations with Hannah Arendt. She has taught at Kew Forest School in Queens (2017-20), at Leman Manhattan Preparatory School in Manhattan (2021-23), and in Argentina at the Escuela Normal Juan Bautista Alberdi. She is currently teaching English online to Argentine students around the world.www.alexandranewtonrios.com