I’ve often said that the ideal collaboration is a dialogue and negotiation, but one must also underscore this: a fruitful working together embodies cooperation and freedom. In fact, the single most important tool in process is freedom; but it resides outside the realm of a happening. For me, and I hope I’m also speaking on behalf of all my main collaborators—T.J. Anderson, Susie Ibarra, Anthony Davis, Chad Gracia, Tomas Doncker, Rhoda Levine, Vince DiMura, Hermine Pinson, Bill Banfield, etc.—when I say the philosophy of process is based on a belief that creative freedom is exacted through shape and control. Each collaborator leans against the other, in an act of embracing, to establish trust. A sense of trust arises not out of a preexisting understanding or schema, but more out of dissimilarity and tension; not for the sake of industry or production, or even as a dare against fate, but more out of the will to achieve a moment of illumination; nothing abstractly complex or elaborate, fashionable or overly stylized, but something almost accidentally singular.

Each artist possesses a knowledge of the other’s obsessions—weaknesses and strengths. Process is the path to surprises. In many ways, yes, dance is a natural metaphor here. A collaboration is a tango of sorts, a system of anticipation, but it is never a tussle. Even if there are moments of push and pull, or when one can almost read or foretell the other’s moves, elements of surprise and passion still drive any successful collaboration. A simple turn is often the gem. This moment is what collaborators live for, when reflection and beauty coalesce naturally out of trust.

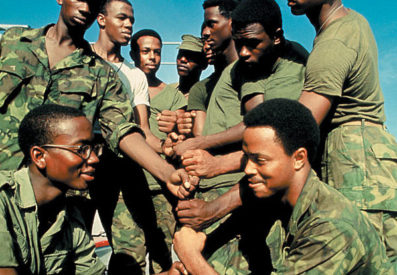

Such a moment is a gift. We hurt to find the shape inside the elemental material. A recent collaboration called Nine Bridges Back is a perfect example. This project began when George Lewis, the director of Jazz Studies at Columbia University, called me and asked if I’d be interested in working on a piece with the violinist Billy Bangs about African-American soldiers in Vietnam. Since I was aware of this musician’s visionary scope, I immediately said yes. And then the wheels were turning. I said to myself: Maybe we could call the piece Sacrifice; maybe it could embrace the unspoken, unacknowledged contributions of black troops in the Nam.

Finally, after numerous phone calls and e-mails, and hectic schedules, Billy and I met at 5 o’clock one afternoon at the Bowery Poetry Club for coffee and tea. We sat there sizing each other up, and I said, “Well, Billy, I have this idea. I think this could be absolutely wonderful.” He said, “Uh huh.” I said, “There were fourteen or fifteen young black soldiers in Nam who threw themselves on grenades to save their platoons or squads, and maybe Sacrifice could be a tribute to them.” He said, “Man, have you listened to my music?” I said, “Yeah.” He said, “I’ve been doing my thing for years. All my pieces are tributes.”

When I left that meeting, I knew our performance at the Harlem Gatehouse would be in two parts. Also, I now knew that this piece wouldn’t be entirely composed of new works: I’d have to embrace collaborators with whom I’d worked before. I began writing two new short pieces: “A Translation of Silk” and “Looking for Black Lang.” At first, I decided to call my half of the evening Twelve Bridges Back. George Lewis, however, informed me that my collaborators would have only 45 minutes on stage. I cut three pieces. In that moment of cooperation, as I returned to the drawing board, Nine Bridge Back found its shape, its heart. It became an assemblage of music and language based primarily on experiences of the war in Southeast Asia. I had to remember that a collaboration is a synthesis, a negotiated personality that lives within and outside each contributing artist. A third thing or being, a feeling, exists because of cooperation. We see interactive glimpses of ourselves in a work.

Originally published in Teachers & Writers Magazine, Volume 40, Number 4.

Yusef Komunyakaa’s numerous books of poems include Taboo: The Wishbone Trilogy, Part 1 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2004); Pleasure Dome: New & Collected Poems, 1975-1999 (2001); Talking Dirty to the Gods (2000); Thieves of Paradise (1998), which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award; Neon Vernacular: New & Selected Poems 1977-1989 (1994), for which he received the Pulitzer Prize and the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award; Magic City (1992); and Copacetic (1984). Komunyakaa’s prose is collected in Blues Notes: Essays, Interviews & Commentaries. In 1999, he was elected a Chancellor of The Academy of American Poets. Yusef Komunyakaa is the Senior Distinguished Poet in the Graduate Writing Program at NYU.