In the winter of 1971, I was subsisting, barely, selling self-printed books of my own poetry along Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley. One late night I stumbled into a bar and was greeted by a woman we called Sister Mary, who sported full nun drag with vermilion lipstick, a modest wimple barely covering explosive blonde waves. “How ya doin’, John?” Not so good, Sister, pushing my poems on the street is really getting me down, so much rejection… “IN JESUS’ NAME,”—the good Sister placed both hands on my head as I suspended my considerable disbelief—I ask that this good man may find a rightful livelihood that can support him and his family. Amen.”

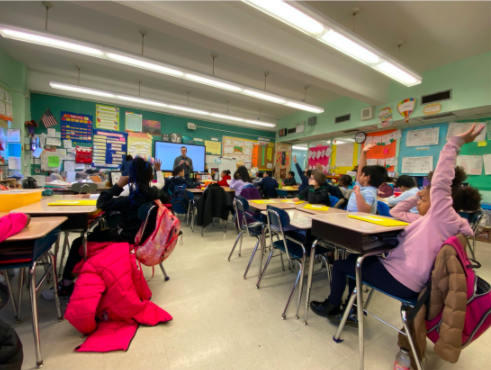

Thirty-six hours later I got a call from California Poets in the Schools. Did I want to teach a workshop at Oakland High School? Over nearly a half-century since then, my day job, as blessed by Sister Mary, and wearing many hats as I followed and inspired the funding, has been teaching kids to write poetry.

I had an epiphany in that first workshop at Oakland High. A couple of sessions in, I gave them Word Cards, an exercise handed down from the late Stan Rice, whose wife Anne became better known for writing about vampires. Open a poetry anthology and let interesting words pop out at you until you have a word on each of several hundred index cards. Deal four to each kid, write a sentence using them all. A kid I hadn’t particularly noticed stood up in back and read:

I’m the Neanderthal Man.

—George Smith, age 16, 1971

I spread my wings and make things happen.

In that moment, my paradigm changed. I understood that poetry was universal. Since then, I’ve been following the implications of that insight.

Myra Cohn Livingston, in The Child As Poet: Myth or Reality?, unleashed a diatribe against the romantic idea of the child as natural poet. Fearful for the future of her vocation of writing poems for children, Cohn Livingston cited examples of plagiarism and sloppy writing acclaimed as “genius” by eager young poet-teachers, aiming thereby to challenge Teachers & Writers Collaborative and the entire poet-teaching movement. But Myra extolled my work on her western coast as a counter-example: “In some instances there has been growth, none so striking as that of John Oliver Simon in California who has moved from a belief in the quick assignment, the instant product, to establish instead a program with concern for process.”

Setting aside her agenda, Myra Cohn Livingston put her finger on something crucial. As Philip Lopate wrote in Journal of a Living Experiment: The First Ten Years of Teachers & Writers Collaborative, our offerings were eternally “stuck on Step One: meet the Poet.” As long as poet-teaching remained a niche program, unfamiliar to the vast majority of schools and teachers, we needed—we still need—fail-safe exercises to nail a cold sell. Word Cards! I Am From! Wishes! Lies! Dreams! Did you hear that kid play the Paganini, and it was her first lesson!

I knew right away I wanted to go deeper than the standard five-session workshop allowed. In 1973, I gathered a handful of eager eighth-graders for the first of several long-term after-school classes I’ve taught over the decades. I want to sketch a few of the very young poets who made an intensive commitment to practice their craft. They and their ilk are why, at age 75, I go on doing this work.

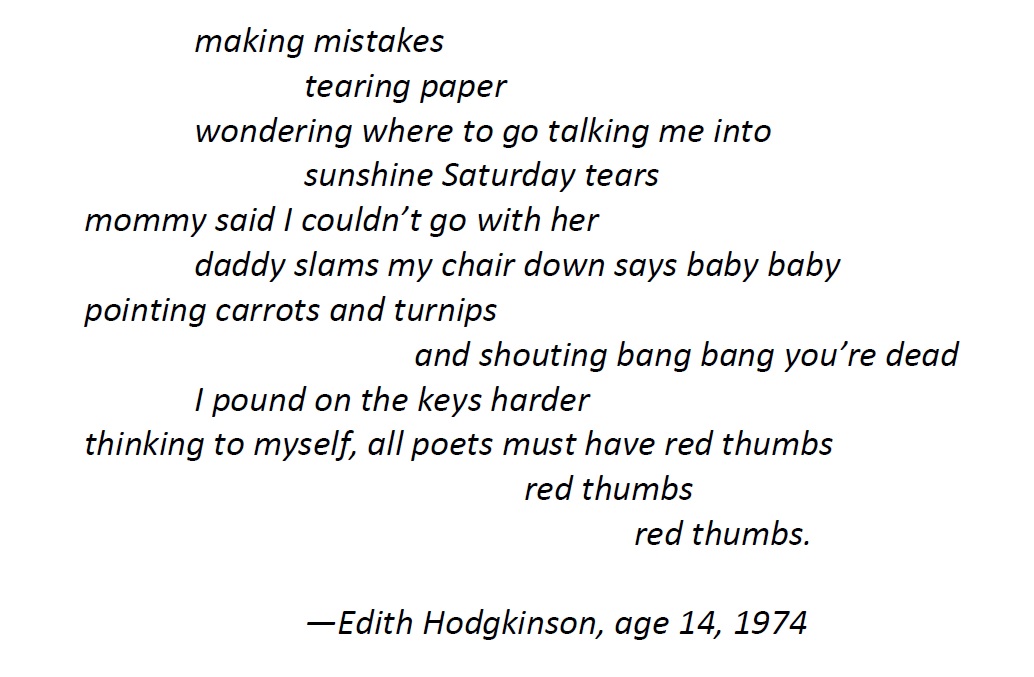

My first after-school workshop had two brilliant, but very different, lead poets, Edie and Leesa. Edith Hodgkinson was ferociously shy, full of rage, and perilously anorexic. I don’t know if Edie ever followed an assignment. If she did, she turned it to her own purposes. Edie refused to share her poems in the workshop. “I’ll only read my poem if you’re all dead,” she allowed. So we played dead, slumped on chairs and sprawled on the rug, and Edie read her poem. This is the ending of “Typewriter Morning.”

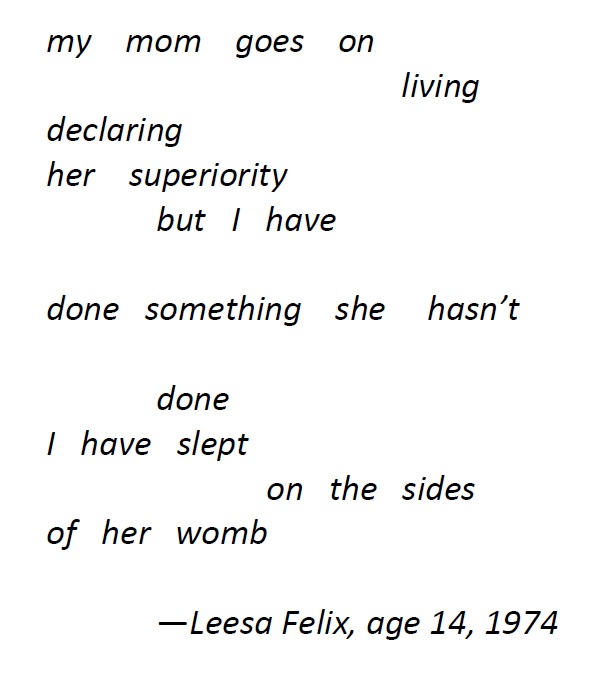

At twenty, Edith Hodgkinson had a chapbook from Hanging Loose. Leesa Felix had not quite Edie’s intense verbal pyrotechnics, but was saner, deeper, less self-centered, more universal.

Leesa, now Lisa Smartt, is working with the metapoetic last words of the dying. Her new book is Words at the Threshold: What We Say As We’re Nearing Death.

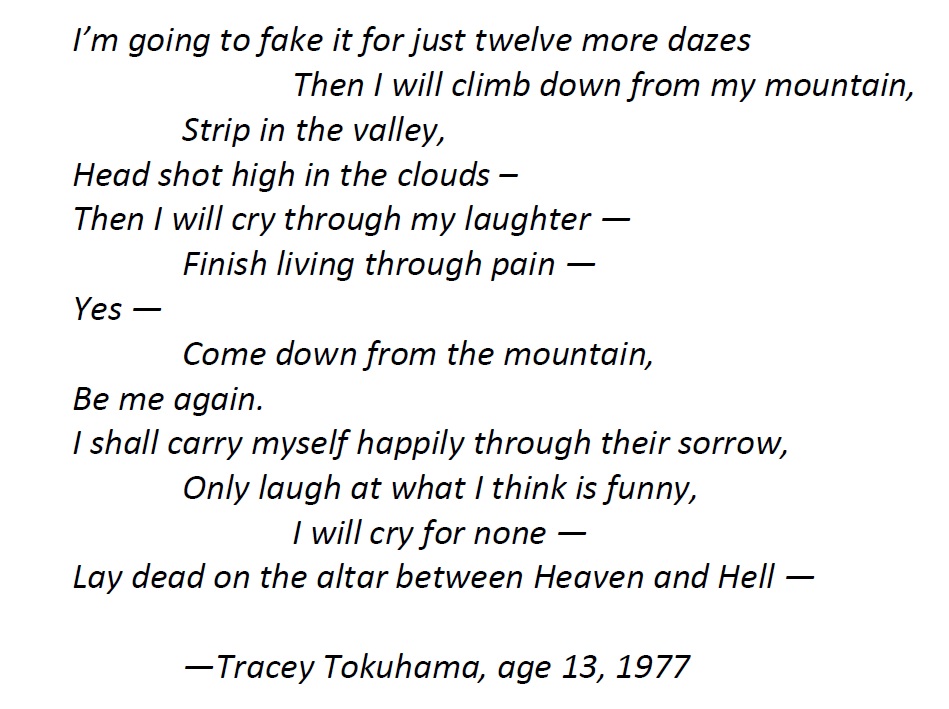

The most exciting poet in my next after-school workshop was Tracey Tokuhama. All fall, Tracey was writing amazing poems, and I was saying “Yay, Tracey, beautiful imagery, powerful metaphor…” and then, on Halloween evening, she went up to Tilden Regional Park in the hills above Berkeley and swallowed a bottleful of aspirin. By miracle she was found and saved, her stomach pumped, and a couple of days later her 80-page manuscript arrived in the mail, lovingly posted to me before her attempt, and I found that Tracey had been telegraphing her intent in plain language and fooling me with dazzling poetry. This is from October 19:

I recently caught up with Tracey Tokuhama-Espinosa, long-married to an Ecuadorean diplomat, and a world authority on the neuroscientific benefits of raising multilingual children. “I wasn’t in great pain, or anything like that,” Tracey confided. “I just wanted to see what was on the other side.” Couldn’t you wait? I asked. “Well, that’s what I’m doing now!” Since then I have always been immensely alert for red flags in student poems.

I fell in love with Spanish in the 1980s and started travelling southward, meeting and translating poets and exporting poet-teaching in the process. I got a grant from the Witter Bynner Foundation to train local poets in Mexico City, using the resources of the world-famous Museo Nacional de Antropología. Everyone in the D.F. was telling me, “¡Tienes que conocer a Jorge Luján! He’s doing great things with children’s poetry.” I was amazed to find that Jorge Luján, a skinny exiled Argentine poet-musician with a marvelous laugh, who had never heard of Kenneth Koch or T&W or CalPoets, had independently invented the wheel of poet-teaching at the very highest level in his Thursday afternoon workshop. I was the first person Jorge had ever heard of, let alone met, who was doing similar work with kids’ poetry, and naturally we became hermanos de por vida.

In the Sala Tolteca of the Museo, 1000-1200 CE, at the time when Tula was the metropolis of Mesoamerica, one sees a repeated theme of a human face in clay or stone— maybe the god Quetzalcoatl—emerging from the jaws of a predatory bird or beast. I told these chilango kids to write about the animal inside you, or the animal you’re inside. Soledad Funes, who had been practicing in Jorge Luján’s workshop for a couple of years, wrote:

El tigre es un animal

que sólo tiene dos vidas:

una dentro de mí

y la otra en el cuerpo del espacio.The jaguar is an animal

—Soledad Funes, age 10, 1986

that only has two lives:

one inside of me

and the other in the body of space.

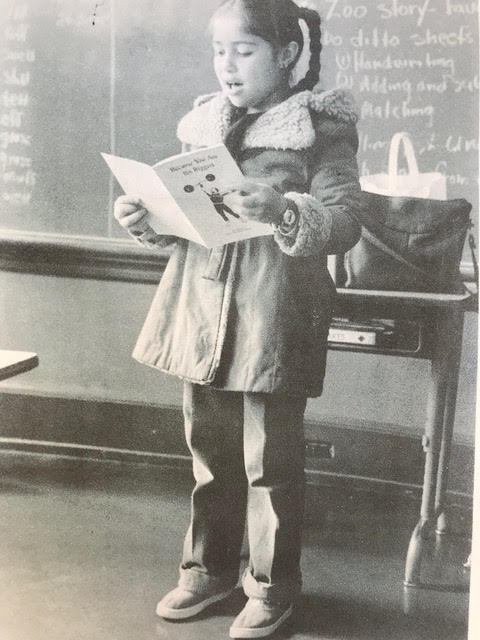

I met Carmen Jiménez in a bilingual third grade in the Fruitvale barrio of East Oakland. Carmen’s folks are from Todos Santos Cuchumatanes in highland Guatemala. Spanish and English are her second and third languages; her first is Mam, one of 23 living Mayan tongues. Here, Carmen knocks off her own version of Lorca’s “Romance somnámbulo (verde que te quiero verde)” that I had had her class translate from Spanish to English the previous week:

Blanco que te quiero blanco.

Blanco como las alas del ángel

bailando en las almohadas blancas…

Blanca mariposa que nadie ha visto

le decimos Misteria BlancaWhite how I love you white.

—Carmen Valentina Jiménez, age 8, 2006

White like the wings of an angel

dancing on white fluffy pillows…

White butterfly that no one has seen

we call it White Mystery

After teaching I taught Carmen for three years in East Oakland, she made the long trek from middle school to my Friday after-school class in Berkeley that featured a cluster of diverse but largely middle-class River of Words finalists. When Carmen read Anne Frank in high school, it gave her permission to write poetry about the genocide back home. Now Carmen is at UCLA on a full ride, first of her family and second of her language to attend an American university. She is majoring in linguistics, with the goal of compiling a dictionary of Mam, which would be the first of its kind.

Recently I asked Carmen Jiménez the college student to reflect on what Carmen the third-grader learned. She told me, “Poetry became ‘the light that saved me.’ Words suddenly took on individual forms and shapes to create visual spectacles beyond what I would see every day during the few hours every week that our Poet-Teacher, John Oliver Simon, dedicated to our third-grade classroom. All the experiences that seemed to stay shut in my mouth now had a way to escape. Unlike other days in class where there always seemed to be an order to things or an expected answer to everything, during time in class with our Poet-Teacher Mr. Simon, answers multiplied by the minute. Eleven years later and as a sophomore in college the memories of those classes still remain.”

When we encounter a brilliant student poet, we may be tempted to turn the spotlight up loud and let everyone bask in the plaudits. This may not always be a wise strategy. The greatest poem a student of mine ever wrote, and to my certain knowledge the greatest poem ever written by an 8-year-old, begins with a couplet from Jorge Luján’s workshop. Jorge had his kids compile a Diccionario de la imaginación, supplying one-liner poetic definitions of familiar things. Lisi Carrión Parga (age 7, 1985), defined Dragones as estufas que corren (Dragons: stoves that run);and when we translated Lisi’s poemita in my Friday after-school workshop, third-grader Caroline Woods-Mejía—half-Guatemalan, half-Swedish, and all-Berkeley—was off to the races:

Rising smoke

dragons fly

stoves that run

and never return

you feel down in the dumps

YOU KNOW, SUNK.Rocks that clatter and chatter

there will be no

silent rock

scribbling and writing

messing up the paper

pancakes steaming in the oven

running shoes racing you…

run, shoes run…

Starting with dragons of runaway stoves, Caroline’s poem was running for its life, and she kept racing it, writing and writing, “mad that this poem isn’t over… trapped in a series of poetry,” for a full week of scribbling, only to conclude 117 lines later in the following Friday’s workshop with triumphal alliteration:

I’m stuck, I’m stuck

in the words

ROPE or R-O-P-E.Pink bubblegum popping on my nose

orange, pink, light blue, purple

the sunset right ahead of me

rain in front of me

hail bumping on me

rusting tigers roaring in the rainbow

rattling like a snake

snickering hyenas, stinky skunks

going back in time.The clocks are backwards

—Caroline Woods-Mejía, age 8, 2005

pencil wackle, tickling tightropes

bubbles that float up in the air

whacking walruses, roaring rhinos rolling,

zipping zagging zebras

There, there it is, the spider

that I saw. It’s spinning

the web of life.

Caroline was awarded the River of Words Grand Prize—though she escaped from the podium before Robert Hass could ask her what she meant by “wackle”—and was henceforth trotted out like a star gymnast at poetry benefits. Co-equally billed with Bob Hass, she read to a thousand people in Sacramento. But meanwhile, in our Friday workshops, Caroline lost her magisterial confidence. Nothing she wrote—and she often wrote well, winning another ROW Grand Prize for a creek poem—could possibly top “The Web of Life.” A dozen years later, a senior at UC Santa Cruz, Caroline Woods-Mejía is still a poet, and she has finally emerged from the shadow of her 8-year-old genius. Caroline remarks dismissively of her college workshop peers: “They have a lot of angst, but not one of them has heard of Pablo Neruda!”

My current after-school workshop in North Oakland is once again led by two brilliant but very different young poets, Greer and Brisa. Greer Nakadegawa-Lee began writing poetry with CalPoet Lilian Autler in third grade, and by the time I caught up with her in sixth, she was ready to rumble. Greer’s first impressive poem came from a composite exercise. I had the kids translate, with copious scaffolding, a 20-character Chinese poem by the immortal Tang Dynasty poet Dù Fú, that combines politics and ecology, beginning 國破山河在,Guó pò shan hé zài, literally nation broken; mountains, rivers remain. In the following session I gave them a 14-line frame and asked them to transform their translation into, in effect, an unrhymed sonnet.

Different

People, cast out, all alone together

Burdened by being different in skin or sex,

Different from the mannequin of normal

That paragon of a misguided absolute.Within the walls of an old, old building

Out on the streets of a bigger town,

Pointed words slice without reservation

Echoing through minds with that sharp, harsh sound.Fire in my face, my heart, hatred spreading like a bruise,

My heart beating faster for those people

In the spotlight of insults that shouldn’t be.Insults like searchlights, seeking, targeting those

—Greer Nakedegawa-Lee, age 12, 2016

Who can’t fit a puzzle piece of society

Within its predetermined pattern of normal.

Greer told me, “Mr. Simon, you have to start an after-school poetry workshop.” Brisa Trollinger signed up for the class and came faithfully to our neighborhood library every Friday afternoon. Brisa had seizures as an infant, was slow to start speaking, and could be difficult to understand when she did. Elementary school was endless boring speech therapy pullouts and bullying “because they hated anyone different.” Brisa’s writing felt awkward. Whenever she shared a poem, she would preface it by saying, “This is really bad.” It wasn’t always easy to see progress.

Then, in Brisa’s second summer of writing poetry, a door seemed to open. It was as if she understood at last that all she had to do was tell the truth. Brisa’s poems poured out white-hot, and the craft she didn’t know she had—but had been absorbing through frustrating lessons—rose abundantly to the occasion as she poured everything onto the page:

I was raised in a place where I am alone surrounded by millions of people

—Brisa Trollinger, age 13, 2017

In a place where my only ally is the trapped me

I was raised in a place where children point and laugh

As they forget the devotion of feelings

I was raised in a world where no one is safe

in a place where we are all in danger

I was raised in a place where racism is funny

Where people fight for their rights

Where rich get richer and poor get poorer in a world where we all suffer

In a world with so many flaws it could cover the earth

in a place so sad it could be an empty cup

We often see kids who bring instant brilliance to poetry. Edie, Carmen, and Greer showed their spark on the first day of workshop, and as the weeks passed, they continued to shine in poem after poem. But things were different with Brisa. She came to my after-school workshop for more than a year before the light suddenly broke through, and suddenly the pathway to poetry opened up for her.

Last month, Brisa was rehearsing her poem with me outside the venue before a feature/open starring Bob Hass, when a slightly cooing adult accosted her and asked if she was a poet. “Apparently,” she replied wryly. Later that evening, Brisa’s mom took me aside and told me, “You are saving her soul.”

Saving kids’ souls. That must be why they pay me the big bucks to teach poetry.

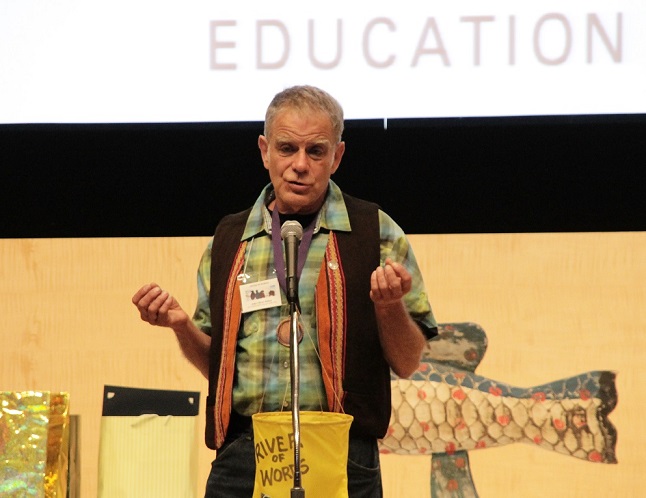

John Oliver Simon was a fifth-generation Californian born in New York City in 1942. Educated at The Putney School, Swarthmore College, and the University of California Berkeley, Simon was mentored by John C. Adler, Jeffrey Campbell, Daniel Hoffman, Gary Snyder, Lew Welch and Carol Lee Sanchez.

As an educator, Simon devoted himself to teaching children to write poetry. He was a board member of California Poets in the Schools. In 2013, he was named the River of Words Teacher of the Year by former US Poet Laureate Robert Hass

Simon was also a noted translator specializing in contemporary Latin American poetry. His cultural reporting was featured in Poetry Flash and American Poetry Review.

In 1989 Simon was awarded an Individual Artist’s Fellowship by the California Arts Council. He also received an NEA Fellowship in Translation for his work with the great Chilean surrealist poet Gonzalo Rojas (1917-2011).

John Oliver Simon died on January 16, 2018.