I am quite naturally drawn to a myth in which

—Jean Cocteau

life and death meet face to face.

Ever since childhood, I’ve been attracted to the Greek myths, a lifelong fascination which has led me, as both a classroom teacher and a poetry workshop leader, to try to make these stories come alive for teenagers. The myths—with their timeless themes of journey and heroism, loyalty and passion, ambition and betrayal—give us vivid images to explore and offer voices or masks from which to speak. Their sensuous imagery and mystery continue to shed light on what it means to be human. Who can forget the warm drop of oil falling from Psyche’s lamp onto sleeping Cupid’s arm? Ariadne’s golden thread winding through the labyrinth? Leda in the grip of the swan, or trees swaying to the rhythm of Orpheus’ lyre? And what young person could not imagine the exhilaration of Phaethon’s horses tugging on their reins? These images, if we let them enter our reverie and become translated through our senses, can become powerful sources for writing. When I ask students to write from figures in Greek mythology, my goal is to find ways for myth and personal experience to combine, so that students can imaginatively refigure both the ancient tale and their own lives.

One way to do this is to introduce Greek mythology through film, visual art, and poems. I take students to the Detroit Institute of Arts, where they can see a Leda and a Maenad within just a few feet of one another, or, in another gallery, Aristaeus, the Pan figure in the Orpheus myth from whom Eurydice was fleeing when she met her death. You don’t have to look far into European art to find figures from Greek mythology. If you don’t live near a museum, bring in postcards or art books with color reproductions. Bullfinch’s Illustrated Mythology is a great resource. I also use Edith Hamilton’s Mythology, selections from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and a collection of contemporary poems that can make ancient themes come wonderfully alive. These include Hilda Doolittle’s “At Ithaca,” Katha Pollitt’s “Penelope Writes,” Stephen Dobyns’ “Odysseus’ Homecoming,” Margaret Atwood’s “Circe: Mud Poems,” and Linda Pastan’s “On Rereading The Odyssey in Middle Age”—all contemporary takes on Homer. A ninth-grade McDougal, Littell literature anthology presents the myth of Daedalus, retold by Bernard Evslin, along with a reproduction of Pieter Breugel’s painting “The Fall of Icarus.” I’ve supplemented these with modern poems such as WH Auden’s “Musée des Beaux Arts,” Anne Sexton’s sonnet “To a Friend Whose Work Has Come to Triumph,” and Robert Hayden’s “0 Daedalus, Fly Away Home.” Rita Dove’s Mother Love recasts the Persephone myth into a rich collection of mother/daughter poems, with both contemporary and mythical settings.

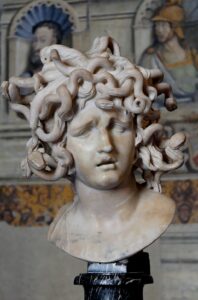

As a classroom teacher, I’ve used the Greek myths to stimulate word study (requiring students to learn the meanings of labyrinthine, halcyon, tantalize, herculean, panic, and lyric, and their connections to Greek mythology), reflective writing, formal essays, discussion groups, and class presentations. Myth study can be lots of fun. It may, on occasion, result in pleasant personal surprises for the teacher: one student’s treatment of the Persephone myth, for example, cast me as the goddess Demeter rescuing its author from the death of inspiration, a bleak, imageless underworld where she’d been seduced by Hades, a.k.a. “Writer’s Block Harry.” A highlight from one ninth-grade class included an Oprah-style talk show that featured Orpheus (dressed as quite the dude, in a bright yellow suit and carrying a guitar) confronting the Maenads, and an intricate board game in which the winner was first to arrive at the Elysian Fields. The game included such pitfalls as the River Styx and a square labeled “Medusa’s Lair: You are turned to stone. Lose one turn.”

Another way to enliven the Greek myths is to use storytelling. The telling of a tale is a shared communal experience, a living act, that honors the oral tradition and builds common ground in the classroom. Telling a story is itself an act of imagination. When I tell a story, I somehow enter the world of that story. When students listen, they do the same thing: they create the world of the story for themselves. We may all hear the same words when Orpheus crosses the river into the underworld, but each one of us imagines his or her own river. Because myths are so rich, students will find different scenes, characters, or images that resonate for them.

One summer my fascination with myth and story led me to enroll in a workshop with Laura Simms at the Wellspring Institute in Mendocino, California. Laura, a master storyteller, helped us develop oral presentations of ancient tales and myths. We worked these stories through mime, meditation, and writing. We created theatrical tableaux based on our stories’ characters; we researched the symbolism of plants and animals in our tales; we created maps and took others on a tour of our story’s landscape; we told our stories to rocks, plants, and trees. These exercises were designed to help us achieve that capacity of the teller to “see” the story, a kind of imaginative staging through which the story comes alive for its listeners.

On our first night, Laura asked us to recall a memory from early childhood and to tell that memory to a small circle of people. The exercise appeared simple, yet each childhood memory seemed uncannily—and unconsciously—connected to the main story the participant was working on. One woman—who had chosen an Icelandic tale about a woman who had been a seal returning to the sea and leaving her human children behind—recalled a large, black stuffed animal that had been a source of childhood comfort after her mother died. A man, whose story was about a father leaving home to seek a fortune, told about his own father returning after a long absence. I had selected Orpheus as my story because I was intrigued by the figure of Orpheus as poet. The childhood memory I told was about stealing flowers from a neighbor’s yard on the way home from kindergarten, then trying to plant them with a spoon in rock-hard ground. The flowers were tulips, so it must have been the first spring after the first winter I’d experienced. (We had just moved from California to Massachusetts.) To me, this memory has come to suggest Orpheus’ journey to the underworld to recapture someone or something loved and lost.

This exercise helped me understand firsthand the connections that can occur between myth and personal experience. It also reminded me of how storytellers often say that their stories “choose them.” It is these psychological, or perhaps pre-logical, dimensions of myth that I value most when using mythology as a source for poetry and imaginative writing. If anyone doubts that mythology can connect directly to a teenager’s everyday reality, consider Justin’s poem:

Grades

—Justin Adams

Like Medusa’s hair

Grades are the sneakiest, crawliest

And only thing wrapped around my head.

I wish I had the shield of Perseus

To protect me from the breath of those teachers

The sword

To slice through F’s and D’s

Or the helmet

To make me invisible

From those annoying, fast-talking kids.

When an assignment is due

For some creepy reason

Something happens. Those questions.

Each one is a snake coming to attack.

How long does it have to be

does it have to be typed

what if I turn it in late

yes, mama, I finished my homework

take that out of your mouth, that’s my homework

can I see that work from last night

can someone turn on a light for this stupid boy

I wish this bus would stop going over so many

bumps

I wish I had wings like Perseus

So I could get out of here.

I am fond of the voice in this poem, and the way the poem takes off toward the end in its crescendo of sneaky, snake-like lines—a deliberate typographical choice. It seemed to me that the poem was a breakthrough for Justin. The Perseus myth gave him a vehicle to tackle a sensitive subject with energy and humor. Without the Medusa figure, I doubt if a poem about poor grades would have worked as well.

Justin’s poem shows how images from myths can express experience in unexpected ways. The Orpheus tale also consistently leads to poignant student writing. One year, we began our myth study by reading excerpts from Edith Hamilton’s Mythology. We also viewed the film Black Orpheus and discussed its symbols of love and death. Students were especially fascinated with the spiral staircase, the “underworld” voodoo scene with churchgoers speaking in tongues, and the Maenads presented as jealous “home girls.” Soon after, as if on cue, a Detroit Institute of Arts film series screened Cocteau’s Orphée. I took a group of students and asked them to jot down powerful or evocative scenes or lines of conversation. This film was no small cross-cultural stretch for my urban students—surrealism and subtitles—but they seemed to enjoy the experience. They compiled a collection of images and phrases, which I typed up and gave them as a handout, adding some tips for working the lines into their own poems:

signing a statement as proof of love

a misty night

Death watching you as you sleep

messages you can’t understand

Death will love you too much

a hand dipped in mercury

a map leading nowhere

shards of mirrored glass

Death in her upswept hair

a train crosses in front of you

judges sit in a panel before you

a hand reaching through a mirror

descending a spiral staircase

a breeze blowing through a room

Many of these phrases create elusive, mysterious effects in and of themselves. I am fascinated by the way a phrase, image, or single word can generate meaning, and I often use lists of lines or single words to trigger students’ thinking. In this instance, the Orpheus story prompted several students to write poems about loved ones who had died. Some of the items from our list found their way, with interesting variations, into those poems.

Daddy

—Rosalind Tarver

I reached to touch you, Daddy,

trying to remember a message

I couldn’t understand.

I walked and walked

but I could not reach you.

I ran to catch up

but a train crossed between us

and when it had finally passed

you had disappeared into

the dark, misty night.

I searched and searched knowing

I would never see you again.

Just in my memory.

Just in my memory—your hazel

eyes, your funny walk with

your head bouncing from side

to side, your words of comfort

breezing through my still

attentive ears.

Orpheus Variations

—NaShawn Reed

1. Father

Upon white satin and lace

he lies motionless.

His black, wavy hair and

thin moustache complement

the pale, cold skin.

Pinstripes travel vertically

down the navy blue suit

like roads on a map

leading nowhere now.

The glint of a thin, gold

pin accents the lapel.

A cherry-red rose

where the heart once lived.

2. Ghost

A cool breeze flows through

what used to be your bedroom.

Three white hooded images

approach my bedside.

I know it’s you.

A masculine hand grasps

the crown of my head,

keeping me still.

The hand is yours.

Your voice whispers

that everything’s okay

but angels hum like a church

choir and my scream for help

goes mute as suddenly

you disappear.

3. Juanita

I step through a mirror

extending my hand to you.

I’m here to rescue you

from the unliving.

You mustn’t stay long

or death will love you

too much.

Let our joyous emotions

guide us. Let

shattered shards of mirrored

glass mark our presence

and reflect our descent down

the white spiral staircase.

Welcome home, Juanita.

On a recent museum visit, I told the Orpheus tale to a group of students as we stopped to consider an Italian Renaissance chest featuring inlays of animals surrounding Orpheus with his lyre. As I told the story, I could see the students’ eyes become glassy and focused far away, in the manner of much younger children who listen with wide eyes and mouths slightly agape—a sure sign that they are “in” the tale, the imaginative space they create as they listen. Later that day, Jerome turned to the Orpheus myth to write about one of his favorite themes, love for an idealized and unattainable female. Much to his (and my) delight, the poem was selected for the museum’s annual student Writing about Art booklet, and its first line was chosen as the anthology’s title.

Orpheus

My poetry is music

Mourning the loss

Of her face,

Her pearl pink Iaugh,

Her feathered touch

That mimicked the breeze.Her voice

Is in every strum

Of my lyre.I play my song

Soothing

Bringing peace,

Tears

To dazzling eyes

That hurt

With whispers

Of what could be.On my lips

—Jerome Williams II

Remains the hum

Of her song

As I ignore

The rocks

And stretch

My heart

To meet hers

In eternity.

Another student wrote from the perspective of Hades:

Hades Speaks to Orpheus

—Wayne Ng

Eurydice of the serpent’s wrath

descends to lower airs

tastes the golden coin

dropped, dropped as a token

while her funeral pyre

soots the sky into bleak clouds.

My collection of riches,

metals and gems

glitter with fire

but cold they are

in this heated dark.

A box of death, a globe of life

form drops of faded memory

in my abode

the shatter of iron tears

that fall to sulfur pools

when the dream of music

plays with my ears.

Orpheus slivers through

opposite lands to implore

for his wife, so one becomes two

embrace, embrace, embrace

the virgin lyre so I can hear

the sweet mint plucks

that glide from one to another

before the taste casts off

into rivers of desolation

lands of air

that can never be reached

obey, obey, obey

may the dance of the trees

whisk your wife away.

Wayne’s and Jerome’s pieces illustrate how myths or legends can inspire persona poems, in which a myth becomes a mask to speak through. Margaret Atwood’s poem “Siren Song” is a perennial favorite, and a fine model to use when asking students to develop a voice from a myth.

Other ways to experiment with persona and voice include retelling a myth as if it were the hottest gossip you’d ever heard or telling it from the point of view of an inanimate object in the story, a minor character, or an imagined character such as William Matthews’ “Homer’s Seeing-Eye Dog.” I’ve also enjoyed having students take a “myth walk” (adapted from Laura Simms’ exercises) in which they walk through the hallways or school grounds in pairs, taking turns telling their myths to their partner, either as straightforward narration or in the voice of a character from the tale. A walk like this is easy to structure. Give the first teller ten minutes to tell his or her story on the way out, the second teller ten minutes to tell one on the way back. The experience of telling while walking can lead to new, almost unconscious, discoveries as students present the myth in a relaxed, informal way.

I will often start my writing workshops based on the Greek myths by asking students what they know about a particular myth (usually more than they think). I ask them to jot down or volunteer elements of the story (images, objects, emotions), which I then write on the board as a source list for writing. I may present contemporary poems on mythological themes and ask students how they might bring the myth up to date. Or I may begin with a storytelling session, encouraging students to pay close attention to the mental pictures that come to them as they hear the story. Sometimes we’ll discuss these pictures. I’ll have them describe the scenes they see or feel most vividly. I may draw a directional compass on the board and ask them to share the different “maps” they’ve imagined, or ask them to give directions through their vision of the story. Does the huntsman turn left or right into the forest? Does the cottage face the rising or the setting sun? Other times, I’ll simply wait a few moments for the spell of the story to recede before asking them to begin writing.

Recently, while conducting a poetry workshop at the Michigan Youth Arts Festival, I tried another approach. I had been spending some time thinking and writing about Icarus and Daedalus, and I wanted to see how that myth might inspire these talented students, whose poetry had won them an invitation to the annual festival. Since the labyrinth is such a dominant part of the story, I decided to start there.

Icarus’ flight is an escape from both the imprisonment of the labyrinth and the societal shame and punishment related to the birth of the Minotaur. Initially, though, I did not mention this—I wanted the students to write without knowing where we were going. I asked them to start by freewriting on the idea of hiding. What kinds of things do we hide—stories, treasures, things we are ashamed of? Where do we hide? From whom do we hide? Is hiding pleasurable? What is it like to be discovered in hiding? Why do we feel the need to hide? After fifteen minutes or so of intense writing, I asked students to volunteer to read. One student had written of his father hiding his love from him. Others had written of hiding places, secrets, and the like.

Then I asked them to freewrite again, this time on the idea of flight. I asked them to imagine the physical sensation of flight and think of as many bodily details as they could. The kinesthetic capacity of words is often overlooked, I think, when we ask students to use the five senses in their writing; movement and action surely constitute a sixth sense. One student, whose poem follows, came up with the idea of backbones turning into wings. Others explored the feeling of flight, how skin or hair might flap in the air, and what to do with one’s arms.

At this point, I introduced the Daedalus and Icarus myth. Many students knew parts of it, and were able to add details as we went along. I read several poems related to the myth, including a recent poem of my own in which I imagine Icarus taking off ahead of his father, seeking the warmth and light of the sun (as contrasted with the gloom of the labyrinth) on a bright and very cold day. We spent quite a bit of time discussing the story. The girls in particular were fascinated by Pasiphaë, mother of the Minotaur, whose lust for the bull was actually a punishment inflicted on her husband by the god Poseidon. We also considered what we could learn from Icarus’ failure to heed his father’s advice, and what it meant that Daedalus survived the tale and moved on into yet another story.

Then I asked them to check back over their freewrites about hiding and flight and to look for images or lines that might fit into or trigger a poem about Icarus. I suggested that they either retell the myth or use it to shed light on a personal experience. I added that they might want either to address their poems to Icarus or to write in the voice of Icarus. (As always, I gave them the option of writing about something else if they chose.) They wrote, intensely, for nearly half an hour, then we shared their pieces. One of my favorite first lines was “Greek boy got his wings.” Some students chose to write in the voice of Icarus. One developed a childhood memory of attempting to fly from the roof of her garage. Eluehue—influenced by rap—set Icarus’ voice to a playful music, in which this adult reader can’t help hearing echoes of bossa nova, Smokey Robinson, and Charlie Parker:

Sun Kite Falling

(once)

I get fly

tango music and

maraca cha-cha-cha

I bumble up in

my be-bop

scat a lil higher

fire fire and desire

cause I’ve got sunshine(twice)

– Eluehue Crudup II

I get so high and so close that I

blind the sun with my smile. I take

handfuls of sun pulp to eat and savor.

I bathe and breathe in the sun,

mango wine and kissing shine

eat and smile and lather

my sunfruit and summerwater.

I am purged in it, yellow liquor-fire,

gold skin and teeth

lungs and laugh dissolve to

thinness and the sun births me

sun spit I fall smiling.

Lauren’s Icarus was much darker, unable to shake the labyrinth:

Icarus’ Destination

—Lauren Fardig

The labyrinth winds its way to a slow

strangle around my heart.

I know what it means to angle upward

and no longer be shackled by a mason’s work.

No more tangle in meaningless conversations

with an uninterested beast.

I am not a canary, putrid yellow, sunk deep in my feathers.

When those wings were strapped upon my aching shoulders

I lost every ounce of anger in my insect soul.

I wanted to stretch my arms into the sun’s welcome blaze

and bring my finger to her lips, the heat so necessary.

But these wings could not take me there.

Destination slips coolly as I proceed downward.

Arms extend toward father’s face.

Waves engulf me with a bitterfrost glass glare.

Other students connected the myth with personal experience or family story:

My grandmother told me once that our

—Meghan Van Leuwen

backbones are wings, more

than useless bone under paper flesh.

Some day they will grow, she said.

They will rip your mortal t-shirt

and bend your child-back.

I wonder what Icarus knew about backbones.

If he had lain quiet on his back on the cool labyrinth floor, he may have felt them, hard against the grey.

His silent life was burdened by the threat of walls

around him, sky above and ground below.

Daedalus had a mind of steel:

creator of cages and places to hide away.

He kept his son cupped in the palm

of shame. Icarus yielded to the curve

of his father’s hand, expected no escape.

Daedalus aimed for wings of wax.

“The sun is on our side,” he thought.

“The sun is like an India rubber ball, and I can toss it far into the sky.”

The Sun Is Lit from Behind by a Wax Candle

Was it 1929 or 1931

when your great-uncle

that Butch Cassidy type

jumped from the sixteenth

story of a Chicago building

above ancient gridiron train bridges

because he knew

that the eastern express would come

knock him flat,

v-shaped,

before he could even

attempt the great Icarus mirror trick of long ago:

flying with skin flapping loosely,

bald head lapping up the sound waves,

the breath of papery wax feathers landing sweetly on his neck,

ground hitting him like the thunderclap of truth,

his feet cut in two,

his money lost flat,

twinkling like constellations below the

trackstrackstracks,easy clickings underfoot.

—Stacey Tiderington

As these poems show, the enduring imaginative legacy of the Greek myths is something students can explore with personal revelation and aesthetic delight.

Bibliography

Atwood, Margaret. Selected Poems: 1965-1975. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1976.

Auden, WH Collected Poems. New York: Vintage, 1991.

Cocteau, Jean. Cocteau on the Film: A Conversation Recorded by Andre Fraigneau. London, England: Dennis Dobson, 1954.

Dobyns, Stephen. Cemetery Nights. New York: Penguin, 1987.

Doolittle, Hilda (HD). Collected Poems. New York: New Directions, 1983.

Dove, Rita. Mother Love. New York: Norton, 1995.

Evslin, Bernard. McDougal, Littell Literature, Orange Level. Julie West Johnson and Margaret Grauff Forst, editors. Evanston, Illinois: McDougal, Littell, 1995.

Graves, Robert. The Greek Myths. London, England: Penguin, 1992.

Hamilton, Edith. Mythology. New York: Penguin USA, 1969.

Hayden, Robert. Selected Poems. New York: October House, 1966.

Matthews, William. Selected Poems & Translations, 1969-1991. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1992.

Ovid. The Metamorphoses. Translated by Horace Gregory. New York: Viking, 1958.

Pastan, Linda. The Imperfect Paradise. New York: Norton, 1988.

Pollitt, Katha. Antarctic Traveller. New York: Knopf, 1983.

Sexton, Anne. All My Pretty Ones. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1961.