2009 Winner of the Bechtel Prize. Originally published in Teachers & Writers Magazine (Vol. 41, No. 2, 2009).

The students call it “shitty college,” and I can’t exactly blame them. In the North Academic Center building, the walls are made of cinder blocks, there are mice in the hallways and the ceiling tiles are falling down. There’s a myth that NAC was designed by an architect whose prior design project was a prison. There are no windows in the sixth-floor classrooms where I teach undergraduate creative writing. In any given classroom there are either not enough desks or way too many desks, a third of which are broken, as though the room is being used for storage. Usually, the trash hasn’t been taken out. Or there isn’t any trash can at all, which means there’s trash on the floor. The blackboard on the wall behind me is nearly white with chalk residue but there is no eraser. A continuous ring of dirt lines the other three walls like an unclean tub. This line of dirt, dark as an insipient mustache, indicates how long it’s been since the walls were given a fresh coat of paint. It comes from hair grease, where the students at the City College of New York, in Harlem, have leaned back their heads to rest.Many of them have kids. Some of them have fulltime jobs. No wonder they’re tired.

“I apologize for this room,” I always begin on the first day. And then I put on Louis Armstrong. Usually I begin with his 1954 recording of “Tenderly,” a kind of slow New Orleans funeral dirge that manages, like all the blues, to be at once depressing and triumphant. The students begin to come awake, smiling and tapping their sneakers against the scuffed linoleum floor along with the snare drum’s insistent, rolling beat.The trumpet slices through the cascading waterfall of piano and clarinet. And because I can’t improve upon Ralph Ellison’s assessment of that particular trumpet’s beautiful sound, I read them the following quote by the unnamed protagonist of the The Invisible Man:

Sometimes now I listen to Louis while I have my favorite desert of vanilla ice cream and sloe gin. I pour the red liquid over the white mound, watching it glisten and the vapor rising as Louis bends that military instrument into a beam of lyrical sound. Perhaps I like Louis Armstrong because he’s made poetry out of being invisible. . . . And my own grasp of invisibility aids me to understand his music. . . . Invisibility, let me explain, gives one a slightly different sense of time, you’re never quite on the beat. Sometimes you’re ahead and sometimes behind. Instead of the swift and imperceptible flowing of time, you are aware of its nodes, those points where time stands still or from which it leaps ahead. And you slip into the breaks and look around.

“That’s what we’re going to do in this class,” I explain. “Slip into the breaks of what we hear and write about what we see.”

I began teaching jazz poetry as an avid fan of jazz music but also as a writer who finds it an instrumental part of her own process. In fact, I have difficulty writing without listening to jazz at the same time. I find it adds color, texture, and rhythm to my work. Knowing how well it frees me when I’m stuck, how well it enables me to play and take risks, I wanted to use jazz with my students in the hope it might do the same for them. I wanted the course to combine listening to the work of 20th-century jazz giants with the interpretation and transliteration of that work by poets (including Langston Hughes, Nathaniel Mackey, Al Young, Jayne Cortez, Sterling Brown, Robert Hayden, and Michael S. Harper). I wanted to explore the historical contexts affecting the evolution of jazz music and the poetry inspired by it.

By now the CD has moved on to the next track, “You’ll Never Walk Alone.” I turn up the volume so the trumpet fills the room. I’ll hold off on getting into a deeper discussion about the “different sense of time” the invisible man talks about and how that sense might manifest in poetic lines on a page until we get to Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk. For now I just tell my students, “We’re going to listen to a different jazz musician every week, we’re going to learn about what made their music innovative, and we’re going to write poems inspired by what we hear.”

“Are we also gonna eat ice cream and sloe gin?” grins Leandro, a lanky young man in a Mets cap. “Oh, hello,” I say, approaching his desk and holding out my hand. “You must be the class clown. I’m Professor Raboteau.” We shake hands. “I can’t legally serve you gin in here, but you can get it ten blocks away on 149th and St. Nicholas Avenue where you can also hear live jazz.”

I turn to the rest of the class. “In fact, if you look at your syllabus you’ll see we’re going to St. Nick’s Pub together in a few weeks instead of having a midterm exam. How many of you listen to jazz?” Four or five of them raise their hands. There should be no more than fifteen students in a creative writing workshop. Mine has twentynine. And this is one of the classrooms without enough desks so a few of my students are sitting on the floor. Many of them are immigrants, or the children of immigrants. Some of them are the first person in their family to go to college. None of them take their education for granted because it is too hard-won. Yet I know there are things about poetry they take for granted and I want to challenge their notions about the form.

“How many of you are here because you thought it would be an easy A?” I ask. Leandro raises his hand and a few others follow suit, mostly men. In my five years of teaching at the City College of New York, very few undergraduates have gone on to pursue creative writing in graduate school or had the luxury to entertain it seriously as a possible career. Even among the English majors, the pressures from family to make money are just too great. They aspire to be doctors, lawyers, engineers.

“You’re sadly mistaken,” I tell the students with their hands raised. “You’ll have to work extremely hard to get an A in this class. But thank you for your honesty. Maybe that quality will make you interesting poets.” It hardly ever does. Not initially. By the time I get them, my students have very codified ideas about writing poetry—that it has to rhyme, for example, or refer to clichés about the moon. As for reading poetry, they find it at best, obtuse, and at worse, pointless. I refer them back to the Ellison quote. “What does it mean to make poetry ‘out of being invisible’?”

They’re shy about answering. I cut them some slack since it’s the first day. I ask them some rhetorical questions instead. What does it mean for a musician to be a poet? Or a poet to be a musician? How are those two things—music and poetry—linked? I hand out the lyrics to another song Louis Armstrong made famous: “(What Did I Do To Be So) Black and Blue,” and we listen to it. One verse goes:

I’m white inside, it doesn’t help my case

’Cause I can’t hide, what is on my face, oh!

I’m so forlorn, life’s just a thorn,

My heart is torn, why was I born?

What did I do, to be so black and blue?

The song’s controversial lyrics help open up the discussion. Suddenly the students have lots to say. Kingsley calls Louis Armstrong “a self-hating brother” for claiming to be white on the inside in order to justify his humanity. Latriece defends the word choice by pointing out that the song was written in 1929 when “times were different, more segregated.” Sidra remarks that we’re still living in a segregated time. Salihah observes that Louis Armstrong didn’t even write the song. Dana struggles to articulate the song’s irony— the very blackness of the singer’s face which he can’t hide and which marks him so visibly is also that which renders him invisible. “This is a mad sad song,” says Christopher, shaking his head. “It’s not just sad,” Dana disagrees. “He’s asserting himself. He’s saying he’s not a sinner just ’cause he has black skin. He’s speaking up to the ones who kept him down.”

We talk about the song as a lament and decide Louis Armstrong is not lamenting his blackness, but the racist world that saw his blackness as a sin. I go over Louis Armstrong’s biography, his importance in jazz history as a brilliant soloist who helped turn jazz from popular dance music into an art form. I talk about the concepts of “swing” and “scat,” innovations Louis Armstrong developed as a vocalist and trumpet player, and “shucking and jiving,” the role he was sometimes accused of in his lifetime. We listen to several more Satchmo songs, some of them purely vocal, like “What a Wonderful World.” I ask the students to extend the same sense of irony they heard in “Black and Blue” to “What a Wonderful World,” which is a song that insists upon the wonderful because the world is also so very awful. Then I play a few purely instrumental songs and ask them to use their imaginations to tell me what they hear coming out of his trumpet.

“Pride,” someone says. “Pain,” someone adds.

“What else?” I ask. “Be specific. Use your five senses.”

A vacuum. A womb. A red light. Mardi Gras. A blue bell. Sponge cake. A brass abyss. A black hole. A clenched fist. Battlefields. Haiti.

I’m encouraged by this list of vivid images. Their assignment is to listen to more of Louis Armstrong’s music and write a poem about what they hear coming out of his trumpet. For extra credit, they have the option of visiting his house in Corona, Queens (now a National Historic Landmark and museum), and writing a brief response paper. But none of the students go to his house and the poems they turn in are, with rare exception, trite, clichéd, kittenish, forced, interchangeable, moon-filled, and rhyming.

My antidote for this? Billie Holiday. Impossibly, only six of them know who she is. “Can you hear how her voice and style of singing are influenced by Louis Armstrong?” I ask them. They can. She doesn’t have a pretty voice, especially in the later recordings, where it’s obviously ravaged by years of hard and tragic living. But I want my students to understand that this is part of what makes her voice beautiful.

“Billie Holiday personalized every standard she sang. It really sounds like she’s lived through the things she sings about. Her style is unorthodox. In fact, some radio stations refused to play her music because she sounded so weird. She plays around with the beat and the melody, sometimes she’s phrasing like a horn. By her own admission, she never sang the same song the same way twice. What can that teach us about writing poems?” I ask.

Silence.

It’s still only the second week so again, I cut my students some slack. I tell them about Billie Holiday’s hard life, her neglected childhood, her moonlighting with prostitution, her debut at the Apollo Theater here in Harlem not far from our campus, her heroin addiction, her signature gardenia, her time in jail. We listen to “Lover Man,” “What a Little Moonlight Can Do,” the melancholy “Don’t Explain,” and her own composition, “God Bless the Child.” Finally, I pass out the bald lyrics to the anguished and uncompromising “Strange Fruit,” with its graphic description of “Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze / Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.” I can talk ’til the cows come home about nuance, but I can’t teach that quality as well as Billie Holiday singing one word of that song.

Their assignment is to write her a letter. In response, I get an embarrassingly awful acrostic and several formal and boring missives. But I also get this gem, from Chongsi: “Dear Billie, wilted flower, we want to save you, but not from the needle scratching your own voice.” The next week I’m excited to move away from music with words. I wonder how the students will respond to Charlie “Bird” Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. Will they find it obtuse and pointless? Jarring? Ugly? I want them to hear how drastically different bebop was from straightforward, danceable swing. I hope its fast tempos, asymmetrical phrasing, and freer structure will free them to be more experimental with their writing. I play “My Melancholy Baby” and ask them to imagine what the instruments are saying to each other. Their assignment is to write a dialogue poem. Anna turns in a piece called, “The Deli,” which begins:

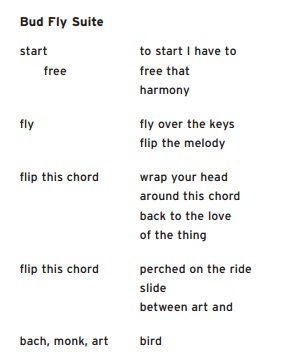

I ask Anna to read her poem to the class, and then hold it up so they can see how she’s begun to play with line breaks on the page. When I ask her what happened, she shyly says, “Jazz happened to my punctuation.” Which is the perfect transition to Bud Powell. The class is compelled by Bud Powell’s tragic biography, particularly by the fact that he was beaten on the head by the police and never mentally recovered. But they are equally compelled by his layered and adventurous piano playing. We listen to some of his major compositions including “Dance of the Infidels,” “Hallucinations,” “Bouncing with Bud,” and “Un Poco Loco.” I want them to hear the way he did away with lefthand stride, using that hand instead to play irregular chords, often while speeding through lines with the right hand in the flighty style of Charlie Parker.

For her homework, Sandra turns in a striking poem with two columns, reflecting Bud Powell’s two hands. She explains that it’s a poem for two voices, so we read it to the class simultaneously, me taking the left and her taking the right:

I’m thrilled with the risks Sandra’s taken in her poem. As the semester unwinds I notice a similar trend in her classmates’ poetry. Their work is becoming more abstract in form, image, and content. Kazu, who struggles with English as a second language, writes a haunting poem about Miles Davis’ eyes, in which she compares his trumpet to “a glass of angry whisky.” Emanuel turns in a delightfully bizarre poem entitled “The Length of Thelonious Monk’s Beard Explained,” about the pianist’s invisible, vestigial third and fourth hands. Not surprisingly, John Coltrane takes the class to interplanetary and cosmic realms. Coltrane’s sheets of sound, multi-phonic modes, and chord changes result in a stack of dense and complicated pages.

On a Monday night in the middle of the semester we take our class trip to St. Nick’s Pub. I want them to appreciate that so much of what we’re studying was born in Harlem spots like this one—the Lenox Lounge, the Savoy Ballroom, the Cotton Club. Gabriella recognizes the house band’s first tune. “That’s ‘No Room for Squares’!” she shouts, and the bandleader bows in her direction. (We had listened to Hank Mobley the week before.)

As an added benefit to these developments, the students are also paying more attention to rhythm. After listening to “Freedom Now Suite,” Christopher says Max Roach has “killer bees in his hands” while Simone actually tries to approximate the drummer’s sound in her poem “Four Limbs,” about domestic abuse:

it takes 1 bang from 1

beat 2 make its mark

it takes 1 bang from

1 bam 2 bruise this hide

it takes 1 bang 2 make 1 black

n blue covered n red

it takes 1 bang 2 bam

1 boom n slam this hardened hull

Simone’s title was inspired by this quote by Max Roach: “In no other society [than drumming] do they have one person play with all four limbs.” I want them to hear that just as Billie Holiday could make her voice sound like an instrument, Max Roach could make his drum kit sound like a voice, by paying as much attention to a song’s melody as its beat. We discuss the concepts of counterpoint and layering, and now when I ask my students how a musician is like a poet, they have plenty of ideas. As poets, they write musically. They use refrains. They think about volume, tempo, subtlety, white space, silence. The bizarre.

By the end of the semester, several of the students have begun recognizing jazz riffs sampled in hip hop and rap. They’re excited to discover that jazz isn’t just their grandparents’ music; that it’s a strong and lingering influence on much of the music they listen to today. Some of them have begun downloading Charles Mingus and Cannonball Adderly. They make each other mix tapes and swap them in class. They also give each other feedback on their poetry. On the last day, Leandro lingers behind to hand me a homemade card. “I want to thank you, Professor Raboteau,” it says. “You changed the way I hear.” My instinct is to tell him he has the loveliest “brown nose” but he’s still not getting an A. Instead, I take stock of this young man who’s made giant steps as a poet. “I want to thank you, Leandro,” I smile. “You made this piss-poor classroom seem like it had a window.”

Photo courtesy of Gavin Whitner

Emily Raboteau is the author of the novel The Professor's Daughter. Her book of creative nonfiction, Searching for Zion, is available from Grove/Atlantic press. She recently received tenure from the City College of New York, where she teaches creative writing.