Bechtel Prize Judge Garth Greenwell selected Éireann Lorsung’s essay “The Slowest Writing in the World: We Use a Needle and Thread to Learn to Write” as the 2024 Bechtel Prize runner-up. The Bechtel Prize is awarded for an essay describing a creative writing teaching experience, project, or activity that demonstrates innovation in creative writing instruction.

The Bechtel Prize is named for Louise Seaman Bechtel, who was an editor, author, collector of children’s books, and teacher. She was the first person to head a juvenile book department at an American publishing house. As such, she took children’s literature seriously, helped establish the field, and was a tireless advocate for the importance of literature in kids’ lives.This award honors her legacy. Learn more about the Bechtel Prize here.

By the time you have reached the fourth year of college, you have learned speed. You have learned it because you have needed to complete assignments for the five classes you are taking at one time and there are only ever 24 hours in a day; you have learned it because your boss called this morning and offered (“offered”—you know not to turn these “offers” down) an extra shift, and now you are cramming your reading in on the bus from work to campus; you have learned it because, like me, you spend a lot of time on social media, where the dominant tempo is immediacy. You pride yourself that you can write a whole essay in five hours on a Saturday. You should be proud: you have worked really hard to meet the demands of the educational, economic, and social systems that we live inside, that shape our imaginations. These systems reward your ability to adapt to their demands and the pace of those demands, and so you have. You have done this well. When you haven’t, you often feel this is a personal failure: you talk in office hours about feeling like there is something wrong with you. You say you feel pressure to be “successful” by the time you graduate with your BA. You are stressed. You want very much to be good, but it seems more and more that to be good at all will mean going even faster.

And you are tired.

Speed is wearing. We know this about machines and we know it about ourselves. Speed is wearing, and it wears us into its groove until all there seems to be is speed, and the only possibilities that appear on the horizon are the ones that speed offers: more and faster. But we are tired, tired; we are burning out. We have the sense that there is too much to do and never enough time for it, we miss our friends, we miss our families, we can’t concentrate, we don’t enjoy reading anymore (although we can remember having enjoyed it, in childhood, and we have the impression that things were not so fast paced then), we have the sense that we are hardly there when we are doing anything, our minds are always skipping through what we’re doing now in order to be ready to do whatever’s next. We are optimizing, and it is rubbing us raw.

We have the sense that we are hardly there when we are doing anything, our minds are always skipping through what we’re doing now in order to be ready to do whatever’s next.

When my students come into the classroom tired, overworked, burnt out, I understand their exhaustion and its consequences even though it is (they are) different to my own. When they are distracted and anxious, when they talk about the simultaneously soothing and refracting effects of social media, they help me recognize those same effects in my own life. We live in a world where those effects and consequences are so widespread as to become nearly invisible, below the threshold of perception or of language. The writing classroom is a place where shared work and shared imagining can make it possible to see what is difficult to see. It is a place where we can learn to perceive and make decisions about our relationships to things as fundamental, and as slippery, as time.

Since 2017—more intensely since the turn to screen-focused learning of the COVID-19 pandemic—I have grounded my writing and teaching in attention to time and place. My students’ and my own struggles with precarity, social media, isolation, and the intersection of hustle and art has led me to center writing as a process, rather than means to a publishable end. Because this can feel confrontational to students who have understandable worries about grades, doing things “right,” and success in terms of words written and pieces published, I have spent a lot of time working out ways to do process together, rather than talk about it to them. Shared process in the writing classroom gives us an experience of time that relies on concentration, thinking slowly, perceiving in detail, and patience. Because my students are so skilled with speed in language, reorienting toward process has required me to find ways to change how we use language and what it means to write. Part of this has been to insist on using our hands to learn: writing by hand, yes, but also doing handwork, walking, drawing. These practices foreground the embodied nature of writing and thought, and they all take time.

The writing classroom is a place where shared work and shared imagining can make it possible to see what is difficult to see.

When I began to think about time in the writing classroom, I turned to how my own teachers helped me experience duration and caesura: the commonplace book, a place to collect quotations, stray thoughts, language without a target, a book made for the making rather than for the end result. My first forays into helping undergraduate creative writing students experience slow time involved teaching them to make their own commonplace books by hand, then asking them to attend to their ordinary lives through a series of daily exercises throughout the semester. Instead of resulting in a poem or an essay, the exercises supported students in understanding how vital it is to preserve space and time in which to have ideas, make observations, imagine, and learn to look. Drawing the same thing daily for a week, practicing deep listening, and taking walks in their neighborhoods helped students experience writing as a process, one that both takes time and arises out of the time we spend making synaptic, imagistic, linguistic, intellectual, and felt connections across the activities of our ordinary lives.

I knew that students’ disfluency in these modes, their encounters with their own lack of skill, would be frustrating. I foregrounded to my students that I valued their encounters with frustrating things. Frustration seems of deep importance to a writing life—not for its own sake, not morally, but as a marker of difference and complexity. In the case of practices like drawing, students met the unfamiliar technique and materials and were forced to move much more slowly to record their perceptions than they would have had to in language. Sometimes, their skill with language allowed them to forget that it is a medium, that we use it. Exercises that immersed writing students in the unfamiliar act of connecting their eyes with their hands to make a drawing rather than a sentence taught them in an embodied way that, whether the act yields a Δ or an A, it is a mediated one. In a reflection, one student wrote that this reminded them of the time that looking takes. It is not instantaneous; neither can it really be simultaneous. To do it well, it takes its own time.

Frustration seems of deep importance to a writing life—not for its own sake, not morally, but as a marker of difference and complexity.

Another aim of the commonplace book was to help students encounter their own lives as worthy of regard and as productive of enquiry. This is not unrelated to the question of time in the writing classroom: we spend most of our time in the world of ordinary things, carrying out ordinary actions, in ordinary places. The enchantment of speed has as a correlative the suggestion that there is something out there that could be exciting enough to write about, and if we could just make our lives like that we would have something to say. I have learned from writers as disparate as Leslie Marmon Silko, James Baldwin, Bernd Heinrich, and Christina Sharpe that interest and richness of thought, the grounds of artmaking, reside precisely in our most local and familiar surroundings, processes, and relationships. These writers have further taught me—often through conversations about their work, with students—that attention to the close-at-hand, refusal to consider anything beneath notice, is related to the ability to see, name, critique, and dismantle the subtle systems of oppressive power in which our lives and writing are held. Those systems can feel as far away from everyday life as finishing a novel or collection of poems. And yet, both works of art and the immensity of systems such as racial capitalism, heteronormativity, and national borders come into being in and through our everyday lives and actions. I wanted to help students experience this on a small scale that might over time, in their own lives, transform their understanding of what it means to say that nothing is beneath notice. I wanted them to try committing to the seemingly unimportant, to spend their time on things that might feel unworthy of regard.

“Collect one thing each day that you would usually throw away,” I said. Maybe not organic matter—something paper, plastic, metal; something you can tape into your commonplace book.

“That’s it?” a student said. “No writing?”

“No writing,” I said.

“OK then,” the student said, shaking their head. (In their reflection on this exercise, they wrote about their doubt. How could collecting garbage teach them about writing?)

During our next class, students shared their pages of garbage. The act of collecting and compiling small, throwaway objects had changed those objects: the fruit stickers and cellophane wrappers had interest now. They resonated with the places, events, and contexts of the students’ lives. I have questions about the things I collected, the doubting student wrote. They make me wonder why I collected them, but also about where they came from, why they exist. They make me think about how related I am to other people, in factories, collecting trash, farmers. I feel like they could be the beginning of writing. The commonplace book as a general practice, and exercises like this one, gave my students new ways of relating to time, to their own writing as a process rather than a product, and to the world of their direct perceptions and ordinary encounters as rich and interesting, not to be passed over.

It seemed to me that for this class on attention, the question was how to learn to write slowly, and how to learn this in a deeply embodied way . . .

This past semester, I taught a topics class called “Attention” to fourth-year undergraduate writing students at my current institution. The major written outcome of the class was an extended work of experimental nonfiction about ordinary life. In support of this, we read and discussed recent works of literature as models and theorizations of attention, including Sara Baume’s Handiwork, Christina Sharpe’s Ordinary Notes, Jenny Odell’s How to Do Nothing, Juliana Spahr’s That Winter the Wolf Came, and Emily Hasler’s Local History. Our discussions looked at how social movements, philosophy, artmaking, housework, personhood, and of course writing happen little by little, over time. Each of these writers’ work showed us the power of accretion. What feels fragmentary in the making can, by requiring us to work across a span of time, create space for things we could not otherwise have thought.

Each week, students spent time with their commonplace books, training themselves to look with patience, revisit well-known sites without dismissal, and to see with increased complexity. In class, we did things that at first made several students say out loud, But that isn’t writing! As the semester went on, however, it was the students themselves who said, out loud and in their written reflections, That, too, is part of writing. The semester’s most striking moment arose from exercises that accompanied our reading of Sara Baume’s book Handiwork, an extended essay about duration, artmaking, writing, and grieving that takes the form of hundreds of short passages.

In an advanced writing class like this one, students experience their own mastery of speed, a mastery gained through careful and demanding practice across their degree. Speed has rewards and practical uses. But I knew my students already knew how to write speedily, and I had seen the signs of speed—haste, carelessness, imprecision, impatience, superficiality—show up in student work, as they did in my own. So it seemed to me that for this class on attention, the question was how to learn to write slowly, and how to learn this in a deeply embodied way, not by the application of rules but by the experience of slowness itself. How would I work with advanced writers to practice this slowness?

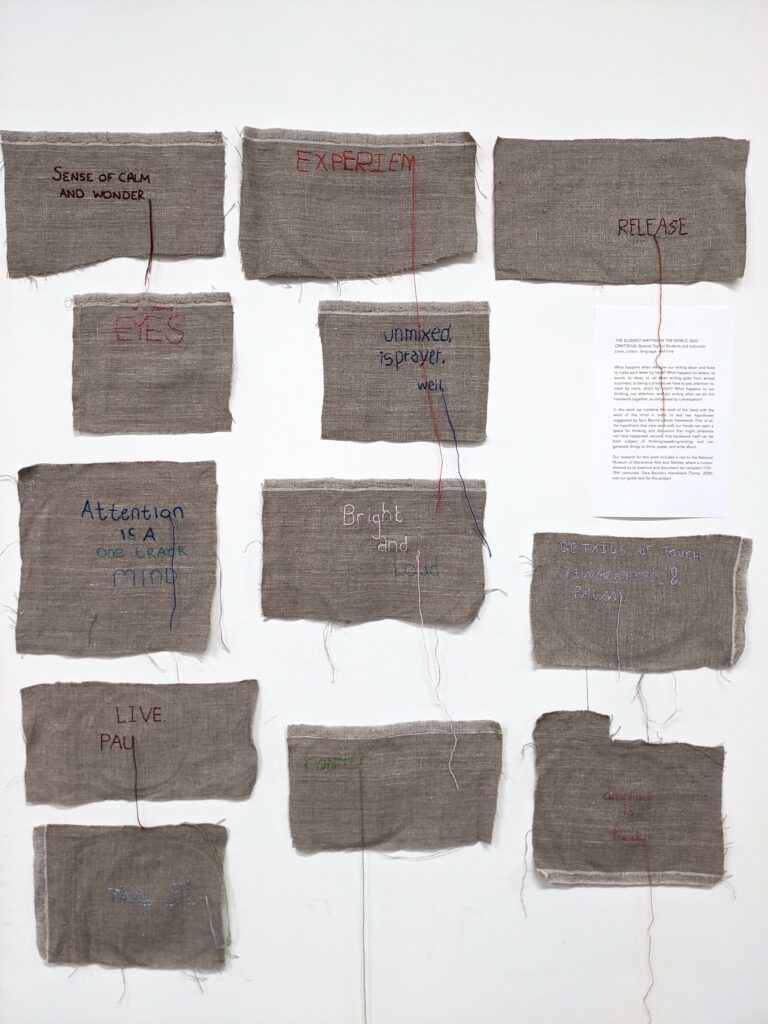

One answer came to me as I prepared teaching materials over the summer. It was a very rainy July; I was rereading Handiwork. I had already imagined taking students to see samplers at the textile museum as one context for Baume’s work. I had imagined we would write thick descriptions as a way to experience the density of information in those complex visual objects, and by extension how long they must have taken to make. But, I thought, what if we made samplers? What if we extended “writing” to mean all kinds of lettermark-making? What would happen if we slowed down time as much as embroidery does?

In the classroom, the 12 of us sat around the table. Copies of Baume’s book lay among linen and thread, embroidery hoops, hands helping other hands thread needles.

“Let’s start by writing reflectively,” I said. “Think back on all you’ve read so far, all the work you’ve done in and out of class. Try to come up with a sentence that defines your experience of ‘attention.’ What is it? What’s it like?”

They went to work in their commonplace books, and I, too, wrote in mine—about the bits of Weil we had discussed early on in the semester, and her statement that attention “unmixed, is prayer.” After a few minutes, I asked them to choose one word, either directly from what they’d written or suggested by it. “You’ll embroider the word you choose,” I said.

We set to our embroidery, talking as we did so about Baume’s book. Students had written areas of interest and questions for discussion on the board at the beginning of class so we could easily refer to them. Conversation ebbed and flowed gently. Later, one student remarked to me that they found the “sewing bee” both difficult—sustaining attention in conversation and in what their hands were doing—and enriching. “I had never done something like that,” they said.

Toward the end of class, I set the steam iron on a window sill next to a folded towel to be our ironing board. The smell of steam floated in the writing classroom as students ironed their pieces of embroidery.

“What if someone sees us through the windows?” one student asked, half joking. “What if they see us ironing, and they say, ‘What are you doing in there?’”

“Well,” another student called back, imitating a posh accent, “then we will just tell them, ‘We’re doing Literature.'”

Everyone laughed; I think we recognized the feeling of doing something that is at once correct and out of order—the feeling of making something together, that meant just what we wanted it to. And I think we laughed because that revealed to us that Literature was exactly what we were doing: both its process—having experiences we couldn’t have predicted, thinking about texts, talking with other writers—and the act itself, making letters, then words, stitch by stitch. Slowly. Inexpertly. One word at a time. Together at the long table, with our own hands.

Featured photo by Dan Cristian Pădureț on Unsplash.

Éireann Lorsung

Éireann Lorsung works in a field of images, objects, movement, and texts. Her publications include Music for Landing Planes By, Her book, and The Century (all from Milkweed Editions). A 2016 NEA Fellow, she teaches at University College Dublin. More: ohbara.com.

Author photo credit: Ann Bartges.