When Sora decided to accompany his friend, Matsuo Basho, on his six-month walking tour across the wilds of northern Japan, he did so both out of care for the somewhat arthritic haiku master and out of his own raging wanderlust. Who benefited whom is up for debate. When I decided to accompany my tenth-grade World Literature students on a six-week tour across Basho’s simple yet pithy lines of haibun, I did so both out of care for my somewhat beleaguered students and out of my own raging passion for 17 th Century Japanese verse. There’s no debate about who benefited whom in this project— I am a better teacher and human having made this journey.

About eight years ago I committed a great deal of personal time and energy into training to become a yin yoga instructor, and through my certification process, I experienced a deepened awareness of breath, patience, and focus— all skills I could use in my professional life as an English teacher. All skills from which my highly anxious students could benefit. In short, yin is the slow-paced practice of holding deep stretches (asanas) for a much longer time than usual, beyond what is comfortable. The practice incorporates principles of traditional Chinese medicine and is meant to stimulate the subtle body or the nadis, in Hatha Yoga. Soon after I began teaching yin, I joined a professor at my alma mater, Loyola Marymount University, to co-teach a first-year course called Contemplative Writing; this experience further shaped my evolving approach to teaching writing to high school students.

In the fall of 2021, I found myself teaching three sections of World Literature at a private high school in Southeastern Georgia, and I took full advantage of that course title by selecting an ancient Japanese text— Basho’s Narrow Road to the Interior.

My heart was heavy with the pandemic stress this generation of teens has had to weather. In a sense, these past two years remind me of another Basho piece, his Travelogue of Weather- Beaten Bones. These kids are a bit beat down. They’ve been fettered to their computer screens for up to eight hours of school five days a week, which does not even include the hours of laptop homework and (necessary) Netflix / Tik Tok chill time. Now that school is in-person, they are masked, hand-sanitized, and quite frankly anxious if not downright lonely. I saw a real need for this unique generation to meet Basho under his plantain tree and sit with him a bit, to sit with themselves quietly. This generation is facing the realities of climate change, school shooters, political turmoil, racial injustice, #metoo triggers, an uncertain economy, and college admission mayhem. Oh yeah, and they’re adolescents in the throes of social and family pressures.

Enter Zen Buddhist poetry and the Walk & Watch Weblog project.

I began by introducing the students to some key terms to familiarize them with Basho’s philosophy of life and poetry. They were particularly taken with wabi-sabi (侘寂), and not just because it’s fun to say. This idea of finding beauty in the impermanence of things resonated with their experience of losing almost two years of their adolescence to COVID-19. Watching a video of the ancient Japanese art of pottery repair with gold-leaf lacquer, kintsugi (金継ぎ), appeared to be a balm to them, a soothing concept that their imperfections are valuable, that they are not broken but rearranged. Finally, these typical teenagers who live a Southern lifestyle of hunting, cotillion, and SEC football were taken by the concept of sabishisa (寂さびしさ)— beautiful aloneness. Here sat forty plus fifteen- and sixteen-year-olds who had been relegated to extended isolation in interest of health and safety; to view the state of being alone in a positive light was nothing short of mind-blowing.

We then read Basho’s haibun (俳文), the quintessential literary hybrid of prose and poetry. Here I worked to train them in close reading, which itself is a kind of meditation to carefully observe the renso (連そ), or web of associated ideas. A proponent of New Criticism theory, I have found success in presenting literature as a self-contained, self-referential aesthetic object. Perhaps that’s just a fancy way of saying I teach the students to engage closely with the words on the page.

When I gently explained that I was teaching them how to read, they promptly reminded me, of course, that elementary school had taken care of that. I then invited them into a conversation about what it means to be able to read in various contexts. They found great joy in reminiscing over the shared experience of reading various middle school literature, which I welcomed and used as a platform to help them realize they have been learning how to read each year. One student commented: “It’s not like we just become better readers each year, it’s that we become more experienced readers.” That she could discern between better and more experienced solidified my belief that young adults today are in fact excellent thinkers. This reading and annotating was mildly frustrating to my students, but with more practice and guidance they began to focus better and therefore harvest more beauty and meaning.

Once they were annotating well, I had them return to their previously annotated page of Basho’s opening haibun and to reannotate it. Basho begins:

The days and months are travelers of eternity, just like the years that come and go. For

those who pass their lives afloat on boats, or face old age leading horses tight by the

bridle, their journeying is life, their journeying is home. And many are the men of old

who met their end upon the road.

And he ends with this haiku:

even this grass hut

could for the new owner be

a festive house of dolls!

Riley marked the personification of time as a traveler, noticing that Basho identified his own journey as a microcosm of all life. Henry highlighted the repetition of the phrase “their journeying,” observing the poetic rhythm reminiscent of David’s Psalms. Savanna circled the euphemism “end,” and connected this fatalistic notion to Elie Wiesel’s memoir Night, which we had recently read together. Ben was intrigued by the virtue of humility in Basho as he offers up his home to the next traveler, hoping they find great joy in his “grass hut.”

Not only did these students experience their own growth as readers, they also had walked like Basho into a new way of writing – the Close Reading Analysis Essay. A favorite essay to teach, the Close Reading Analysis follows the levels of reading comprehension, asking the following questions: What is literally happening in the passage? What is the author doing poetically or rhetorically? What literary, mythological, or biblical connections can we make? What qualities of human nature are at work in the text and still relevant today?

But the true creative breakthrough occurred when I encouraged them to be like Basho and his friend, Sora. I asked them to spend fifteen minutes every weekend walking outside, after which they were to write (in the haibun style) an ongoing weblog. My aim was to reinforce the value of silence, of nature, of aloneness, and of writing. I hoped that perhaps they too would embrace compassion, beauty in imperfection, and above all that the journey is itself home. In short, the Walk & Watch Weblog was meant to create space for these COVID-19 era kids to make a pilgrimage to the interiors of the self. And in doing so, to find solace in an uncertain world.

Luckily, our school offers a longer block period every seventh-class meeting, so I would use thirty minutes of that period to take the students outside to walk. Our campus is unique in that it has a sylvan walking path at its perimeter, one that is primarily used for the cross-country team practices. I led the students on these nature walks to find the joy in a collaborative and kinesthetic activity mid-school day. It gave them a chance to get outside, up from their desks, and away from their screens. Although most walks were far from quiet or contemplative, our time was no less enriching and gave them plenty of ideas to write about. Sticks were picked up, stones were thrown, leaves were overturned, and giggles were heard before the cacophonous non-temple bell signaled it was time to get to the next class.

Much to my delight, the blogs were fantastic! I was struck by how much care they put into writing their haibun style observations while also feeling deep gratitude that they had taken my invitation to heart. After all, how would I have known if they actually walked outside or not? I suspect the assignment was just strange enough to capture some of the more cynical students, just amusing enough to capture the more playful students, and just worth enough points to capture the more grade-focused students. I like to imagine they were also secretly inspired by that bewitching 17th Century Japanese monk.

An additional requirement was to include a visual element to each entry. The edition of Narrow Road did include some pen and ink sketches and maps, but the Japanese characters were the real show stealers. My students were enthralled to see the original Japanese next to the translation to English, often referring to it as “the artwork.” When I put together the scoring rubric for the blogs, I decided to require their own artwork, leaving it up to their discretion. I’m so glad I did!

I also encouraged them to submit excerpts of their blog to the Alliance for Young Writers’ 2022 Scholastic Writing Contest as well as to our school Lit Mag. I was thrilled that they could experience the process of submitting their work for publication, which often serves to build more excitement around and confidence in their writing. Happily, I found that this project benefited my students in myriad ways. Not only did they – and I – meet a healthier perspective on the realities of life in 2021, but also together we became travelers writing beautiful observations, contemplating nature’s brief offerings, and living in the way of elegance.

At the beginning of this essay, I wondered about Sora and Basho, asking who benefited whom? In terms of my students, I declared it was I who benefited most. While I felt satisfied with this project, I noticed I was inspired by my students’ work to seek something more. Like Basho, I wanted to step out of this neatly thatched grass hut my students and I had built together and explore the next interior. My wanderlust manifested in a new creative writing project still in the works. Specifically, I am writing a companion travelog through the perspective of Basho’s friend, Sora. What was he thinking, feeling, desiring, even regretting as he accompanied the master on such a journey? I’m often taken by the helpmate figure, the Eve if you will, and would love to reimagine Sora’s voice during this Zen-style buddy-movie tale, much of which I imagine is rife with humor. Until then, however, I am content having been the Sora to my sophomores’ Basho – every step of this narrow road through COVID-laden 2021.

AN EXCERPT FROM CASSIE’S BLOG:

Today I walked alongside the canal by Eisenhower Park. When I got out of the car, the first thing I noticed was the loud cars above the bridge, and the train tracks surrounded by rocky terrain. After crossing a rusty bridge with holes, I came across an electrical compound bordering the Savanna River. As I was walking the trail between the canal and the river, I saw nine turtles sunbathing together on logs in the middle of the canal.

Nine turtles on logs—

Could they be a family?

Or are they just cold?

The ambient noise of cars gradually transitioned into running water and wind rustling through dying leaves. The ground was no longer rocky but smooth dirt; my feet were quiet besides the occasional leaf. Soon after I heard geese honking to the right of me, and I came across a fork in the road. I turned back. As I was walking back, I found a giant leaf. After the leaf, a great heron appeared beside me, as it was concealed by shrubbery. Unfortunately, I was unable to take a picture of it before it flew away; the leaf had gotten in the way. I found a vibrant plant and several spider webs shaped somewhat like pyramids. Before I left, I found the turtles still sunbathing together.

I walked by the canal again, but this time I started at the headgates. As I walked across the much more stable bridge, I noticed locks of all shapes and sizes hanging onto the railing above the start of the canal.

Waterfalls reflect

Across rusted metal hearts—

We all cling to bars

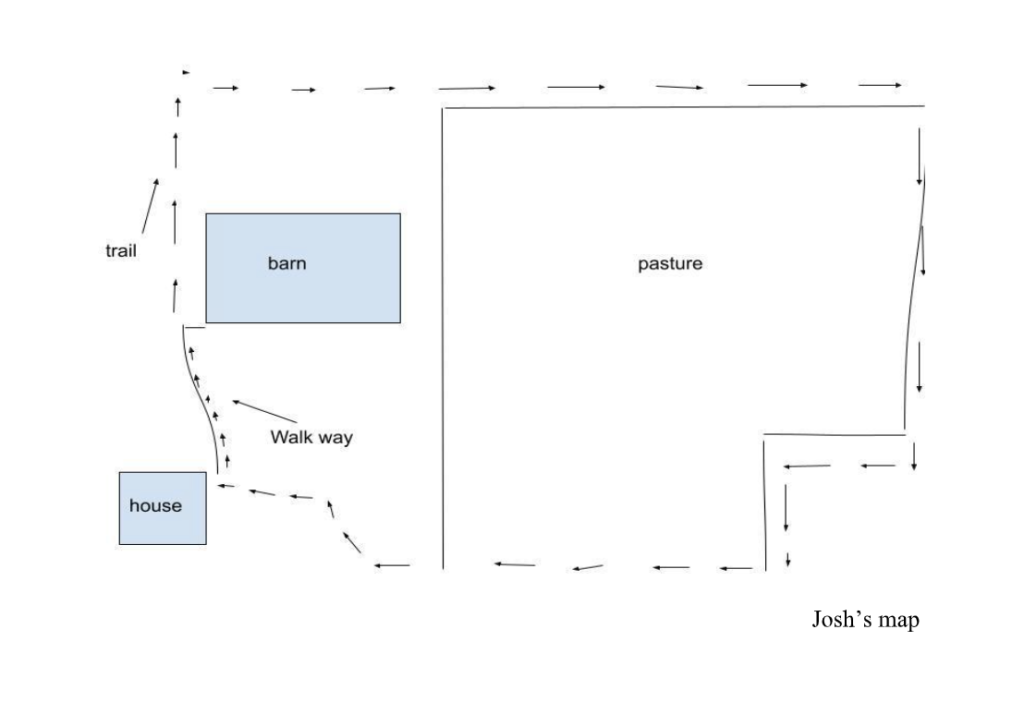

AN EXCERPT FROM JOSH’S BLOG:

Today I walked around one of my pastures, and I saw the peacefulness of the animals, the golden grass of the field, and the calm sway of the branches. I heard the noises of the animals, the wind, and the leaves as I walked. I felt how the leaves crunched, the uneven terrain, and the grass brushing against my shoes. My thoughts wandered from thinking about a soccer game to thinking about food; however, the thing that caught my curiosity was how peaceful my farm is most of the time. The rough terrain was hard to walk on but other than that it was a nice walk.

It’s deer season, so

The hunters are busy now…

There’s a rifle shot

Today I walked around the cross-country trail; although it was not nearly as scenic as my land, I still enjoyed it. I saw trees, dead vegetation, and a dog. I heard a lot more today than I did on any of my other blogs. I heard cars, the wind at the tips of the trees, and dogs barking. I felt almost disconnected from nature here in town. I thought of the different types of families living in each house, and I thought about the different types of cars that drove by.

I caught myself here

getting distracted by noise—

a lack of color.

CANDICE KELSEY currently teaches at a private high school in Augusta, GA. She holds her B.A. from Miami University (OH) and her M.A from Loyola Marymount University, both in English. Candice is the co-founder of a private high school in Santa Monica, CA, and has served as an essay evaluator for both the College Board and the U.S. Department of Education. Her poetry appears in Poets Reading the News and Poet Lore among other journals, and her first collection, Still I Am Pushing, explores mother-daughter relationships. She was chosen as a finalist in this year’s Iowa Review Poetry Contest and Cutthroat's Joy Harjo Poetry Prize; she also serves as a creative writing mentor for PEN America’s Prison Writing Program. You can find her on social media. Her instagram is @candice.kelsey.7 and on twitter @candicekelsey1 For more details visit her website www.candicemkelseypoet.com.