Story Shop, my creative writing program for kids, meets in a comfortable room in an old church in a small suburb in Westchester County, just north of New York City, and has been going strong for over twenty years. My longest-running workshop during that time is made up of eight girls, now in middle school, who have been meeting each Tuesday afternoon since most were in the third grade. Though they are quite diverse in their interests and focus, in their time together they have grown into a remarkably supportive artistic community, one that consistently produces inventive, idiosyncratic, lively work.

I’ve run plenty of groups that don’t have this kind of magic. Some groups I’ve run are very social, but tend to fizzle off into chitchat, without much work getting done. Or I’ve had groups where a few bossy kids vie to take over. Some groups can feel like a collection of isolates—a place where kids focus mostly on private projects. But these Tuesday girls are fiercely loyal group members, and at the same time are on fire to go off on their own and do original work. I believe that the quality of their inter-personal relationships—their general sense of ease with each other, their shared love of mischief, and their emotional openness—has a direct connection to the creative freedom they are able to claim in their writing.

But these Tuesday girls are fiercely loyal group members, and at the same time are on fire to go off on their own and do original work. I believe that the quality of their interpersonal relationships…has a direct connection to the creative freedom they are able to claim in their writing.

What can a teacher do to contribute to this happy dynamic? Clearly, some of this is beyond our control. In often-crowded classrooms, for example, creating an intimate atmosphere—where creative work thrives—can feel next to impossible because of the sheer numbers of kids and too many unpredictable variables. Even the success of my Tuesday group has a lot to do with serendipity—things like good chemistry and luck. But aside from good luck, how is it possible to cultivate the general atmosphere of openness this group shares, especially so that it finds its way into writing?

In my experience, one of the most important things I do as a teacher is to help keep the critical voices that assail these young writers—from both without and within—at bay. This means running interference when kids become too self-critical, or too quick to dismiss classmates or place them into rigid categories. It means creating a general aura of permissiveness. It means keeping the lights down low, figuratively speaking, so no one feels put on the spot, nothing feels irrevocable, and our hour together can feel like a temporary world where anything is possible. The best way to do this, I’ve found, is to encourage a spirit of play in the group.

*

When I first started Story Shop, I tried using a format I was familiar with from graduate school: we would sit in a circle, one child would read his or her work aloud, and then, one by one, everyone would be asked to offer some kind of response or critique. I tried this with even very young kids.

One of the most important things I do as a teacher is to help keep the critical voices that assail these young writers—from both without and within—at bay. …This means keeping the lights down low, figuratively speaking, so no one feels put on the spot, nothing feels irrevocable and our hour together can feel like a temporary world where anything is possible.

Pretty quickly, I saw it was a terrible idea. The children were bored and generally not in the least helpful. They preferred to do cartwheels, rather than critiques. I had to admit that I had hated this format, too, in graduate school. Who wanted to hear what everybody had to say about your work? And the excessive competition and constant comparison this format invited could often cause members of the group to snipe, or be withholding. I had certainly felt these impulses. If I wanted feedback, I preferred an intimate conversation with a trusted reader, someone whose sensibility I cottoned to. But what was a better way to approach running a creative writing workshop?

When I was in college, I did fieldwork for a psychology class two days a week for an entire year. I sat in a nursery school classroom, and, as invisibly as possible, simply observed the kids. I was interested in trying to understand the nature of their play. I took notes, sketched, and eavesdropped. At first I could barely make out what the children were saying, and what I did hear sounded disjointed, incomprehensible. But I persevered.

Gradually I was able to see things I hadn’t before. I paid attention to the intricate block cities erected each morning. I scribbled down everything I heard. I noticed how energized the kids were as they built and concocted narratives to go with their buildings (“The enemies are coming! Get the ladders!”), and how collaborative and collegial they were too, most of the time.

I followed kids as they dug for treasure in sand, cooked plastic turkeys in miniature kitchens. There were bustling, benevolent “mothers,” and ones who were carping and bossy and funny; “babies” who mewed dozily as they were fed, and ones who threw extravagant (pretend) tantrums; there were blow-hard “uncles” who barged in, caused havoc, demanded cash. Everything was alive: the two plastic apples were baby twins; the flickering sunlight on the wall was “lemons.” Children pretended they were smoke. I was careful to be as unobtrusive as possible, just enough off in the shadows, getting to hear the strange story lines unfolding. And there were always story lines.

In fact, I came to understand that this kind of play is the earliest form of making stories; it called for settings, characters, dialogue, back stories, conflict, mood, goals, humor. In a dramatic play sequence, where children were “in” a game of pretend together, the social energy was often vibrant and inclusive. A satisfying play episode made room for everybody. The goal was not to finish or win, but mostly to keep the whole magical thing aloft.

I wanted to see if it was possible to invite this spirit of play into Story Shop. What assignments or suggestions could I offer that might help create a similar atmosphere of openness and exploration? For years now, I’ve been asking myself these questions as I shape the writing workshops I teach. The approach I have developed is not so different from the one I observed in those nursery school classes years ago: I provide materials (collage materials, boxes, toys, keys, envelopes) and an open invitation to “make something interesting to you,” and the kids take it from there.

*

In the time my Tuesday group has been playing and writing together, they’ve pursued hundreds of activities. They’ve built countless scenes in boxes using found objects to create places “where a story takes place.” These have included jails; a mermaid’s headquarters under the sea; a church meant only for rabbits; and an apartment for a man who lies around all day watching TV, to name just a few. They’ve assembled these places into “Wayside Town,” organizing these domiciles along a paper river. They’ve made inhabitants out of clay. They’ve written a newspaper, Wayside Gazette. They’ve spun off and written stories about characters, and these, in turn, have spawned other characters. They’ve made diaries for these characters. They’ve written a group novel whose main characters are pieces of fudge, all of whom live and squabble and compete in beauty contests in the hidden shelves of Bob’s Candy Shop. For a year, when they were younger, they started each session by climbing up a ladder in a storage room, one that led to a trap door in the ceiling. No one ever actually went into the attic space, they just loved the thrill of the climb, then pushing open the trap door and peering into the dark room. It smelled “good” in that space, but “strange.” They loved to imagine what was up there.

Now that the girls are in middle school, they like to linger around the table and talk for a while before they start writing or making things. The openness and playfulness that animated and nurtured their imaginative games now animates and nurtures their conversations. They bring snacks, most often popcorn or chocolate melted over pretzels. We talk about everything: dreams, animals, school, history, friendships, teachers, death, families, boys. Everyone is bursting at the seams to talk, but they seem to listen to each other more closely than they did when they were younger, when—like most kids—they often talked over each other, impatient to get their own turn. Now the girls pause for each other, think about what is said, laugh at jokes, and offer advice and sympathy.

Sometimes I’ll float a question: What makes something interesting? While the girls discuss what is on their minds, describe their experiences, and tell jokes, we are also learning about the nature of characters, of life, and how things hang together. These things are implicit in our close, sympathetic listening. “Long before I wrote stories,” writes Eudora Welty, “I listened for stories. Listening for them is something more acute than listening to them. I suppose it’s an early form of participation in what goes on…. I had to learn to listen for the unspoken as well as the spoken.” In Story Shop, I encourage young writers to cock an ear toward mystery. What is present that isn’t named?

One year I read some of an unlikely book to the Tuesday group. It was Dibbs in Search of Self, by child psychologist Virginia M. Axline, about her sessions with a troubled young child. The girls loved it. In the book, the author seeks to unravel the mystery of why this young boy doesn’t communicate like other children, and why his parents have dismissed him as mentally deficient.

“Each child got out his mat, stretched out on the floor for the rest period. Dibbs got out his mat and unrolled it. He put his mat under the library table, a distance away from the other children. He lay face down on his mat, put his thumb in his mouth, rested with the other children. What was he thinking about in his lonely little world? …What had happened to the child to cause this kind of withdrawal from other people? Could we manage to get through to him?”

Dibbs gradually reveals his experience to the psychologist in unexpected, often non-verbal ways. The book is fascinating in how it helps us understand human psychology. But it also raises writerly questions: How do actions and gestures and details fill in a story about a person? What is symbolic language? What does it mean to have an inner life? These questions encouraged the girls to take a deeper interest in the meaning of things. It also invited them to see the danger in making snap judgments, which, in turn, helped them to free themselves from excessive self-critique. This is serious stuff, but in the community the girls have created, it, too, is rooted in a spirit of play. As one of the girls explained recently, “Story Shop kind of feels like a slumber party. It’s where we can all be ourselves without the fear of being judged.”

*

Sometimes when we’re sitting around the table these days, I think of a game they made up, back when they were in third grade. “Let’s make this a stage,” a girl called one day, referring to a small, recessed alcove in the wall. It was a place where kindergarten-sized chairs were folded and stored. It quickly became a group effort: the girls pulled out all the chairs, lined them up to face the now empty alcove. One chair was put back in.

The recessed space would be called “The Secret Bagel Theatre,” they decided. The girls were smaller then; exactly one child could sit on the small chair wedged into that alcove. We taped Christmas lights around the perimeter. “Ladies and Gentlemen!” a designated impresario would cry. “Time for the Secret Bagel Theatre! Please turn off all cell phones! No smoking! No eating! No talking! The show begins!” She would call off the first name from a playbill we’d assembled. Hurriedly, the first child would duck to sit in the alcove, on the little chair. She would belt out a story she’d written, or sing a song made up on the spot.

Meanwhile, the audience, sitting in the small chairs arranged to face the “stage” fell quiet and listened, although they would also fan themselves, pretend to guzzle food, defiantly smoke cigars. They played the part of an (unruly) audience. But they were also a real audience; they paid rapt attention. It was a pretend show, and a real show. It occupied a middle ground between the two. In this way, everyone listened to each other’s work; everyone had an opportunity to hear her own voice out loud. If a parent were to wander in, or some stray adult, they knew enough to not break the spell. They might or might not be allowed to stay.

The kids are too big to sit in there anymore. They’ve tried from time to time to wedge themselves in, but it’s too uncomfortable; their heads hit the upper shelf. But even though no one fits, the spirit of the enterprise survives. Lately, when we sit around our table, talking, paying attention in our easy way, it’s as if we’re still in that half-lit, half-real theatre, that middle realm. It’s a place where these young writers feel free enough to experiment with language and explore different points of view, to make language their own, to resist conformity, to be fully themselves. To the extent that the Tuesday girls have found this happy orbit, it is because they have learned to hold on to the spirit of play that, week after week, allows them to sustain this temporary world within the ordinary world.

*

It is important to remember that the spirit of play is almost always present in most kids, whether we as teachers are aware of it or not. Kids are always imagining, pretending, daydreaming, although most of this takes place off stage. The younger the kids, the more vividly this operates, but in general this kind of imaginative thinking is going on at all ages, though as children get older, adults are usually less privy to these imagined worlds.

With the demands of large, chaotic classrooms, it can be easy to feel that play, or playfulness, is the enemy of learning or classroom harmony; that being playful breeds inattention, causes kids to go off-topic, can bring out regressive, base impulses. That teaching writing always needs to be a studious, scripted affair. Be serious! is often the refrain of classroom life, especially—as I keep hearing from all my teacher friends—now that testing is of such importance.

In working with a wide variety of kids over the years I’ve run Story Shop (albeit in small groups, but with diverse populations), I’ve come to believe that just the opposite is true: where the spirit of play can be incorporated—expressed through humor, games, and allowing things to unfold organically—creativity flourishes.

So how can teachers bring this spirit of play into their writing classrooms? Where possible, set aside time and space for playful “making up stories,” where the emphasis isn’t on structure or grammar, but on invention and exploration. Don’t try to grade such activities. Suspend all the usual rubrics. Be attuned to different kinds of logic that can infuse tales: sometimes kids’ logic in stories is more akin to the logic of dreams, or the associative logic of poetry. Refrain from jumping in and pointing out confusions or inconsistencies, other than in the most gentle ways. Or not at all. Take pressure off writing by offering a range of other ways to make up stories. (Have a collage table where “junk” awaits.) Be very conscious of not stirring competition, and never force anyone to share if they don’t want to. You’ll find that where a friendly, humorous atmosphere is present, kids most often love to share, to try out new ideas. And sharing to an open-minded, playful group—one where judgment is suspended, at least for the moment—not only strengthens a feeling of unity and harmony, but encourages students to take the risks that produce deep, fresh writing.

Click here to read selections from Story Shop writers.

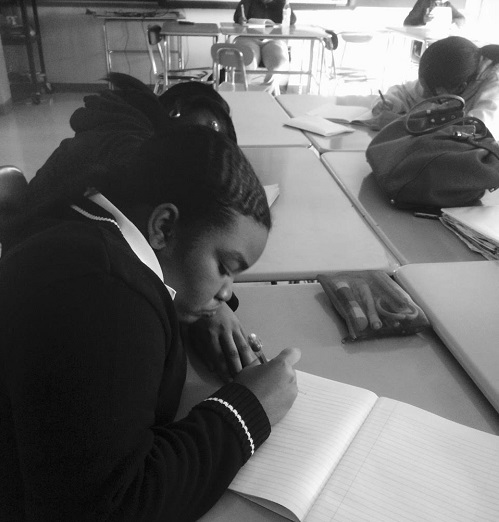

Photo (top) by jarenwicklund

Barbara Feinberg is an award-winning writer and the founding director of Story Shop. She is the author of Welcome to Lizard Motel (Beacon Press), along with essays and articles about creativity in childhood, published in the New York Times, Boston Globe, Education Next, Brain, Child, Teachers & Writers Magazine, and elsewhere. She is working on a memoir about creativity and doubt, called The Wolf in the Garage.