“In a dark time, the eye begins to see.”

—Theodore Roethke

This is the poet Theodore Roethke doing the saying, nearly six decades ago.

Could the times we are living in now be any darker?

It’s true: every generation sees itself as the last. We are post-apocalyptically obsessed. And yet I’m sure, through this, in spite of our own dark times, we will endure. The earth will continue spinning.

Still I wonder: how might the eye in us find something good to grab hold of? What or where or how might we find a kind of peace?

There’s a poem I teach called “Refuge” by Robert Fanning who, like Roethke, is a Michigan poet.

“Refuge” is from Fanning’s third book, Our Sudden Museum, a book of mostly elegies about the poet’s father and sister, both of whom died of natural causes, and a brother who died at his own hand.

It’s about as heavy and dark a book as you are going to encounter, a book that has the heft of a boulder to it, a book that does, though, let light shine up through the fissures in its landscape, like jags of lightning lighting up the dark sky.

I bring in this poem to show my students that no matter how dark things might seem, we can still take refuge in what remains.

What remains is not always the shiny, the polished things of this world; what remains for us to hold onto is often the sullied, and the broken, the darkness itself. We can find strength in the fact that in this, and through it all, we keep on. We are still alive. And what remains is not unlike a map at a roadside rest stop that tells us, “You are here.”

How low do you have be, I ask my students to consider, to take refuge in—”a streetlight blinking in a dead city” or “your well-wrapped grief” or “the broken road that once led home”?

Ground low is how low, I say. Dirt low, I tell them. Underground low. Eyes and ears to the mud low. In the gutter low. Head against the curb low. Head and whole body deep in a hole low is what I say.

But here, I also point out, the poet lifts his gaze and what he sees is what he speaks and is the air he breathes. This is his offering, the words of this world as refuge, as shelter, as home.

“We hang too,” Fanning writes in his poem “The Book of Knots,” a poem written in response to his brother and the basement beam from which he tied that fatal, final knot: “Untie us, untie us, untie us,” the poet as surviving brother begs.

Fanning is writing his way to a new sense of what home might mean in the wake of such grief and loss. His speaker longs for anchorage. He holds on tight to—and finds meaning in—the dirt, the ground itself, into which he scrapes his words, scrawls his poetry.

Here the poet celebrates—even if, in spite of, despite it all. He speaks. He sees. He lives. He carries on. He forgives who he still loves.

And we are carried on by his words and are shown how we too can “take refuge.”

In a dark time, the eye begins to see.

And yes, into the darkness, the poet begins to speak, and speak back.

To speak is to take back. To speak is to stand up. To speak is to be empowered by the act and the resistance of our voice.

Many of my students have lost much: homes, parents, siblings. They carry the stresses of these cold dark times in their eyes, stuffed down inside their backpacks, shouldered on their backs.

To them I ask, What might you see that you might then take refuge in? Not the light of joy, not the light of the lit-up stadium cathedral, but the light of the street’s lone streetlight, the one that hasn’t yet burned out. Not the shiny new car rolling off the assembly line but the car on the side of the road, the tire flat but fixable, the gas tank a hair above empty. Find refuge in that I tell them. Not the perfect, but the possible. What we find when the rust is rubbed off the steel. The hardness beneath it intact. The house with all but a single window boarded up. The garden grown over by weeds with a random sunflower growing. How it got there none of us know. These things happen. A seed gets blown and is carried. It takes refuge in the soil. It finds what little light is offered. And takes root.

Here is some of what these seventh-grade students—Detroit public school students, children who could make the claim that Raymond Carver once staked his pencil to as a kind of writer’s mantra, “I’ve seen some things”—had to say:

Refuge Poem

by Tierra GriffinTake refuge in the shadow

that nobody has stepped into.

In a cloud that never rains.

Take refuge in not knowing

what to say or do. Take refuge

in the tiny piece of ripped paper.

In the inside of a basketball.

Take refuge under the eye bags

because you didn’t sleep last night.

In bricks that float in the air

but never fall. Take refuge.

Take Refuge

by Gregory TaylorIn a tree house filled with animals.

In a city that’s full of hate.

In a school with blinking lights

And rats all over the place.

Take refuge.Car with broken doors.

In a house with dusty pictures

Of your family that is gone.

And a room with nothing but books.

Take refuge.

Take Refuge

by Monica GrahamTake refuge inside a wall no one

can get behind. In a long tunnel

with polka dots on the wall. Inside

a piece of paper that’s never been

written on. Take refuge in the clock

that is ticking. In the dark. Take refuge

outside at night looking up at the sky

lit up with stars. In the silence of a library

while everyone is reading. In the sound

of an airplane moving through the sky.

Take Refuge

by Akira Adams-SheffieldIn the alleyways.

Down the street of abandoned houses.

On the riverbanks

where there is only silence.

Take refuge.

Take Refuge

by Armani JamesIn the abandoned warehouse.

Find a new home in your own mind.

And take refuge.Turn to your favorite blanket

Where your father will cover you up.

And take refuge.Listen to the story in yourself.

Get safety in her words

And in the heart of a tree.In the hippie who stays positive.

Who loves himself and others.

Take refuge.Take refuge in his eyes.

Take refuge in his smile.

In his heart, take refuge.

These are words that these young poets offer up without resistance, without hesitation. These are writers not afraid to speak, to stand up and be heard. When invited to say, to tell it like it is, they will say and tell it like it is. When invited to dream, or imagine, they will dream and imagine. When told to sit down and shut up, these same students will shut down, walls will come up, and this silence will steal their voice.

“A voice,” Margaret Atwood reminds us, “is a human gift.” I carry these words with me into whatever teaching situation I find myself. And here, in every teaching situation, in the words of my students, I find some part of myself I wouldn’t otherwise know. And in those words, in these small pieces of myself reflected back at me through their words, I take refuge.

Let me end with one last poem, a poem for us all to take refuge in, to be blessed with. It’s a poem written by a fourth-grader whose innocence is her guiding light through the dark, whose poetry is a source of solace and balm, a poem that takes us inside a child’s heart:

My Heart

by Kris’Tiana DoveI think my heart is a river

free of pollution

where my true love

is waiting. Or maybe it’s a million

butterflies dancing

in my stomach, or a cat

with all the fish

in the world, or an angel

sent from God

blessing me.

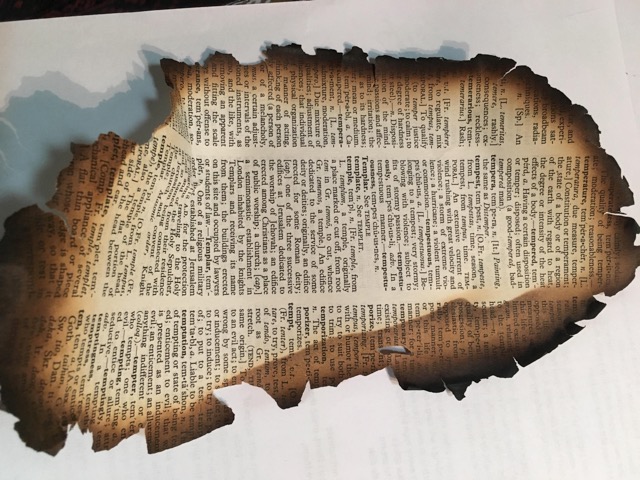

Photo (top) by whereslugo on Unsplash

Peter Markus is the senior writer with InsideOut Literary Arts Project of Detroit, where he has worked as a writer in the public schools for the past 20 years. In those 20 years, he has also published six books of fiction, the most recent of which is The Fish and the Not Fish. He also edited, with InsideOut founder Terry Blackhawk, To Light a Fire: 20 Years with the InsideOut Literary Arts Project, published in 2015 by Wayne State University Press.