Terrance Hayes’ recent publications, So to Speak, a collection of poems, and Watch Your Language, a collection of prose and visual essays, are both forthcoming from Penguin Random House on July 18, 2023. His honors include the National Book Award for poetry and fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. He is a Silver Professor at New York University.

Karisma Price spoke with Terrance Hayes via Zoom on June 6, 2023.

Karisma Price (KP): Before we start, I’ve been waiting six years to tell you this: I was a seventh grader when you taught at Xavier University in New Orleans. I was really interested in creative writing, and I wasn’t in the class at the time, but my middle school creative writing teacher knew this and invited me to come with his class to Tulane University to hear you read from your book Wind in a Box. Then, a little over a decade later, you became my MFA thesis advisor at NYU. And now I teach at Tulane.

Terrance Hayes (TH): Oh, look at how things come around!

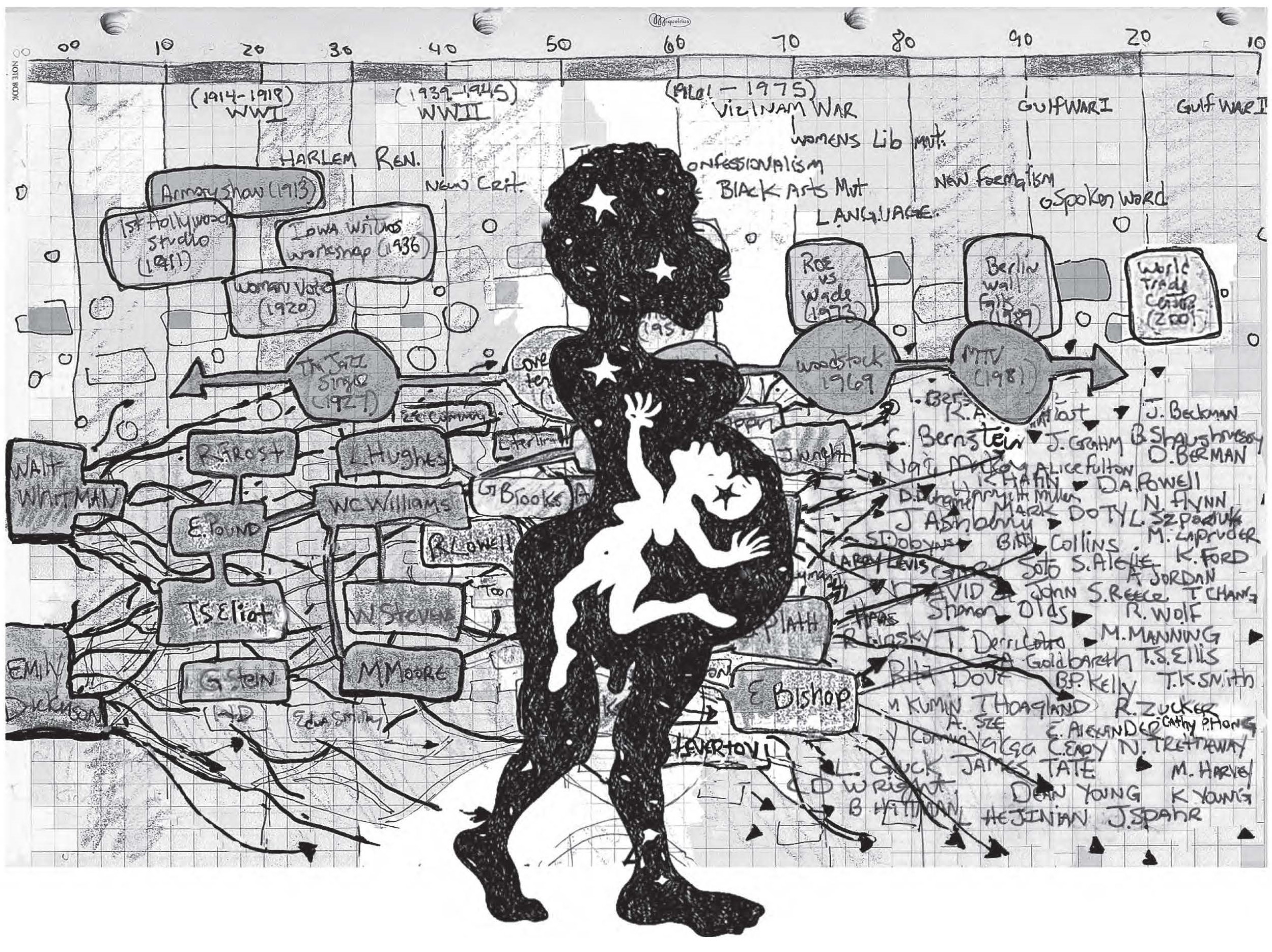

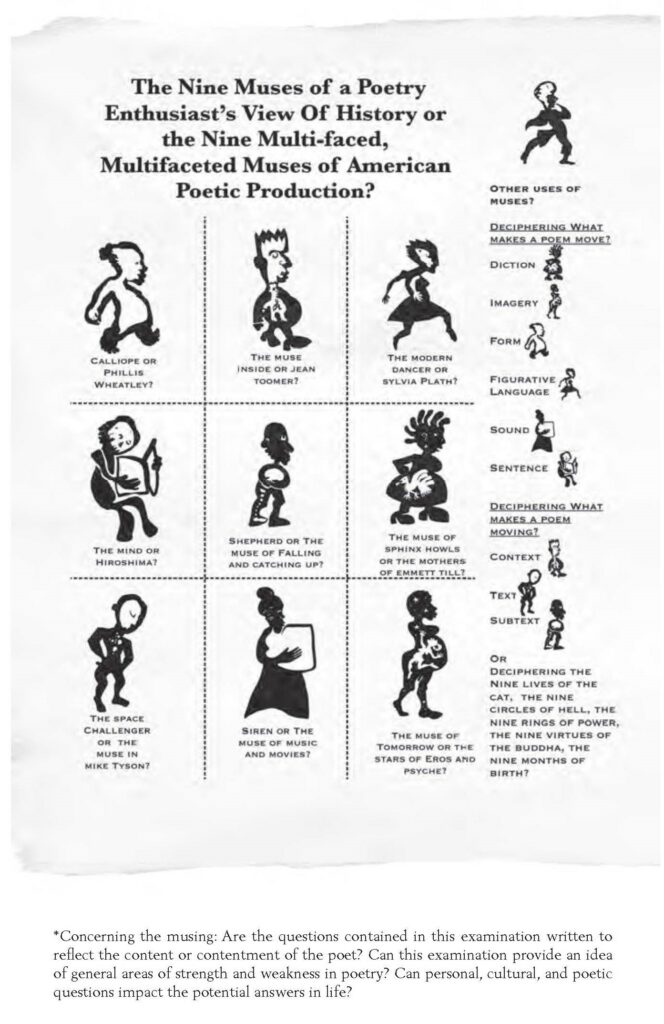

KP: Mhmm! Speaking of the MFA, I remember in our workshop, you drew us a giant timeline of different poets and poetry movements when discussing the literary canon. Who would you say is in your own personal literary canon?

TH: Oh, interesting. In my classes when I teach the history of poetry, I really try to start with where you sit and then go backwards versus starting in the back and coming forward. I just thought very early on, even when I was teaching in New Orleans, it would just be more useful for you to look at your parents first and then look at your grandparents and then look at your ancestors. I always start with the people I know. That’s Yusef Komunyakaa, it’s Lucille Clifton, it’s Toi Derricotte. I think of Patricia Smith more like my aunt than my influence, even though she is. Then there’s Etheridge Knight—I wrote a whole book on Etheridge Knight. Gwendolyn Brooks—I did a whole form on Gwendolyn Brooks. Wanda Coleman is an influence, but also like family. She would be like my aunt/mama. Grandparents might be Robert Hayden, Amiri Baraka, Sylvia Plath. I think Keats is in there among my ancestors.

KP: Who do you think we’d be surprised to hear is an influence on your work?

TH: Prince. I always think about Prince’s hairstyles. I would like to be a poet like his hairstyles. I also think about Prince’s falsetto and his baritone. That too is a good model for how I want to be a poet. But my primary thing with Prince is his relationship to business. Prince was the first person to make me think about the artist’s relationship to the people who put your art out. And he said, and I think he’s right, it’s his work. You’re selling it, but it ain’t yours. You have no jurisdiction over how I wanna make my money or what I wanna do with my poems. There’s not that many models for that. I mean, not successful models. So I never forgot that. It influences my relationship to my own publisher too.

KP: So, you feel like you’ve become a good poem businessman because of Prince?

TH: Yeah, but you know, it’s about advocating for your own stuff. In capitalism, they want you to think that the people who are pushing your work are important, because how else does it get out there? And Prince says, “No, it’s me. I make my work. Even if I just sell it on my own or put it in a vault, it’s still there to be a representative of me.”

KP: I love that. Let’s talk more about your writing. When American Sonnets was shortlisted for the 2018 T.S. Eliot Prize, you said in your video interview that you “write for poets.” What does that mean?

TH: Oh, that’s a good question. Here’s another way of thinking about it: Do you rely on the validation of your audience—which says you sell a million books, and you know you’re popular—or do you rely on the validation of your peers? We are peers because we are poets. So “writing for poets” means writing for readers who write and know the challenges of writing. I’m speaking about people who already have an appreciation of what we do as opposed to people that I have to convince. I don’t trust the notion of writing for “universality.” I think writing for everybody is the same as writing for nobody.

KP: I think about this with my own students. A lot of them want their work to feel universal, which I think is wonderful. I think it’s one of the things poetry is useful for: to make us all share a feeling. I explain to them that the work feels more universal the more specific they get, although to them I know it may feel like the opposite. But when they do get specific, their work really blossoms. And their classmates tend to be very supportive.

Write a poem for your lovers. Write a poem for your siblings. Write a poem for the family for Christmas. That creative gesture in one’s day-to-day life is as important as submitting to The New Yorker.

TH: I think the workshop is a very special place. When you’re around that table, it’s a really sacred, unusual space. Very rarely in your life are you gonna have this kind of intimacy. On a weekly basis people are exposing their vulnerabilities in content as well as composition. They are giving you a lot. It’s not a typical classroom dynamic—the ideal workshop is inherently anti-academic, anti-capitalistic. It’s about aesthetic and personal values manifesting in language. We are not after popularity or generality, we’re after intimacy and personality. I have said to students: “Write a poem for your lovers. Write a poem for your siblings. Write a poem for the family for Christmas.” That creative gesture in one’s day-to-day life is as important as submitting to The New Yorker. As teachers we can show students the rewards of practicing communication and creativity in daily life.

KP: The poems I’ve been writing as of late have been for family members and friends, and I’ve been having them read the poems before I send them to be published, which is new for me. That practice of communicating my feelings to the people who matter the most to me is a very vulnerable, but necessary practice. Speaking of the undergrads, I know it’s not required, but in the spring, you always request to teach them in addition to the grad students during the school year. What do you enjoy most about teaching undergrads?

TH: They are the closest model for how poetry can be useful to regular people. In the undergrad class I teach, I get to pick them. Since Covid, I usually get about 100, 150 applicants. I’m only picking 12. I usually put in about 13, sometimes 14. You’re trying to find creative people and then help them think about their language as a part of their creativity. So I’ll let anybody in, no experience necessary. I’m looking for talent in terms of just linguistic creativity. Giving anyone a better sense that what they do with language is going to help them in whatever else they do. I’m not necessarily trying to encourage my undergrads to become poets.

KP: I teach undergrads and I know many of them want to pursue non-creative writing careers, and I understand that. I find joy when they find joy in whatever they’re reading or writing because I also try to make it clear that they can write about whatever they want in the class.

TH: It’s really why what we do is super important. I say to my students, “This is the only time in your entire college education where no matter what you write about, we will talk about it.” So, if you want us to talk about your breakup, write that poem. We’ll talk about it. If you want us to talk about your depression, how you saw a roach in the bathroom, how the sky is blue—just think about that. It’s the only time where they’re actually dictating the subject. When else does that happen? There’s no other classroom where what you work on is going to be the premier conversation. This is why I say to them the subject of poetry is poetry. When we talk about your content, we talk about your line breaks, we talk about your imagery, we talk about your use of metaphor. We are not just asking, “Why were you sad? Why were you sad?” We might even be asking for a better expression of sadness. We mean to help you give it shape, we mean to offer ways to handle it.

Giving anyone a better sense that what they do with language is going to help them in whatever else they do.

KP: I have some questions about your own writing practice: How does your brain work? I would call you a formalist but at the same time, I think that’s too limiting and contained. In music terms—you’ve been talking about Prince—do you think of yourself as the artist or just the instrument creativity passes through like breath in a trumpet?

TH: Sometimes when a poet takes the stage, there is a performance aspect where the poet themself becomes the focal point, even more so than the poem they are presenting. An example of this is Amiri Baraka. He is recognized as a talented poet, but his impact as a poet goes beyond just his poems. It is his presence and persona that leave a lasting impression. Personally, I feel like I’d get in the way. I do get in the way. I think the poem is more important than how I sound, how I look, my pitch, or anything. Even though the real-time performance is a special element of poetry, the poem is a much more important artifact of what poets do than the poet themself. I thinkthe poem matters more than the poet—if it’s a good poem. I think of myself as the instrument to making a good poem.

KP: How do you balance your writing and teaching time? I know you live and breathe poems, and as a former student of yours, I know how much energy and care you put into the workshop space. Also, I remember you said you only took one workshop in undergrad. How do you facilitate a workshop environment that you feel is beneficial to students?

TH: I took an intro to creative writing class as a sophomore and then I wrote poems by myself. I work like a monk. I think my relationship to poetry is probably like other people’s relationship to prayer. But I’m still trying to figure out how to be more than a poet. I say this to my students, too. It is all creative writing. And this is answering your question about how taking one creative writing class impacts my teaching. I’m a poet, but I think that the notion of us just being creative writers is better than segregating us in terms of like, “here’s the poets, here’s the fiction writers, here’s the non-fiction writers.” We’re creative writers, you know? And that comes from that intro to creative writing class that I took as a sophomore. I still believe that it’s better to be more open to genre than closed off. All we’re doing is bearing witness.

KP: What drives your work and the contents of your forthcoming books?

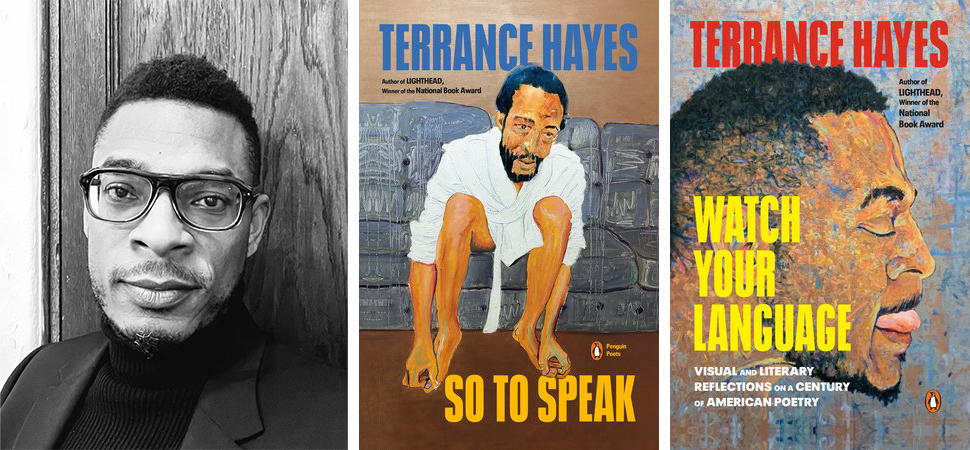

TH: Curiosity. Can I get away with this? Am I gonna say this? How would I say that? Those kinds of basic questions drive the work. And I say that because in the prose book, Watch Your Language, is an essay [2019 Blaney Lecture] that I read at NYU. It’s online. It’s 225 questions. For example: “Do you think modernism is real? Do you think Gwendolyn Brooks should have won the Nobel? Do you think the poet is more important than the poem?” And when the book came, because there’s so many questions throughout it, I broke the essay up into nine parts like the nine muses, and each section has a question to it that’s asking a thing. So much of what the work winds up being is inquiry.

KP: Will you be traveling for a tour of your new books?

TH: I do nothing that makes me have to cancel my classes. It goes with what I just said to you, and it is a very specific Terrance thing. I feel like my poems are more important than me. No matter what I seem like in my body. When it’s all said and done, we’ll know when I’m not around to distract people if the work is really working. But I just feel like I’m always in the way. I’m much more useful as a teacher.

Karisma Price

Karisma Price is the author of the poetry collection I'm Always So Serious (Sarabande Books, 2023). Her work has appeared in publications including Poetry, Indiana Review, Oxford American, Four Way Review, Academy of American Poets Poem-A-Day Series, and elsewhere. She has received fellowships from Cave Canem and New York University, was awarded the 2020 J. Howard and Barbara M. J. Wood Prize from the Poetry Foundation, and is the 2023 winner of The Stanley Kunitz Memorial Prize from the American Poetry Review. A native New Orleanian, she is an assistant professor of English at Tulane University and holds an MFA in poetry from New York University.