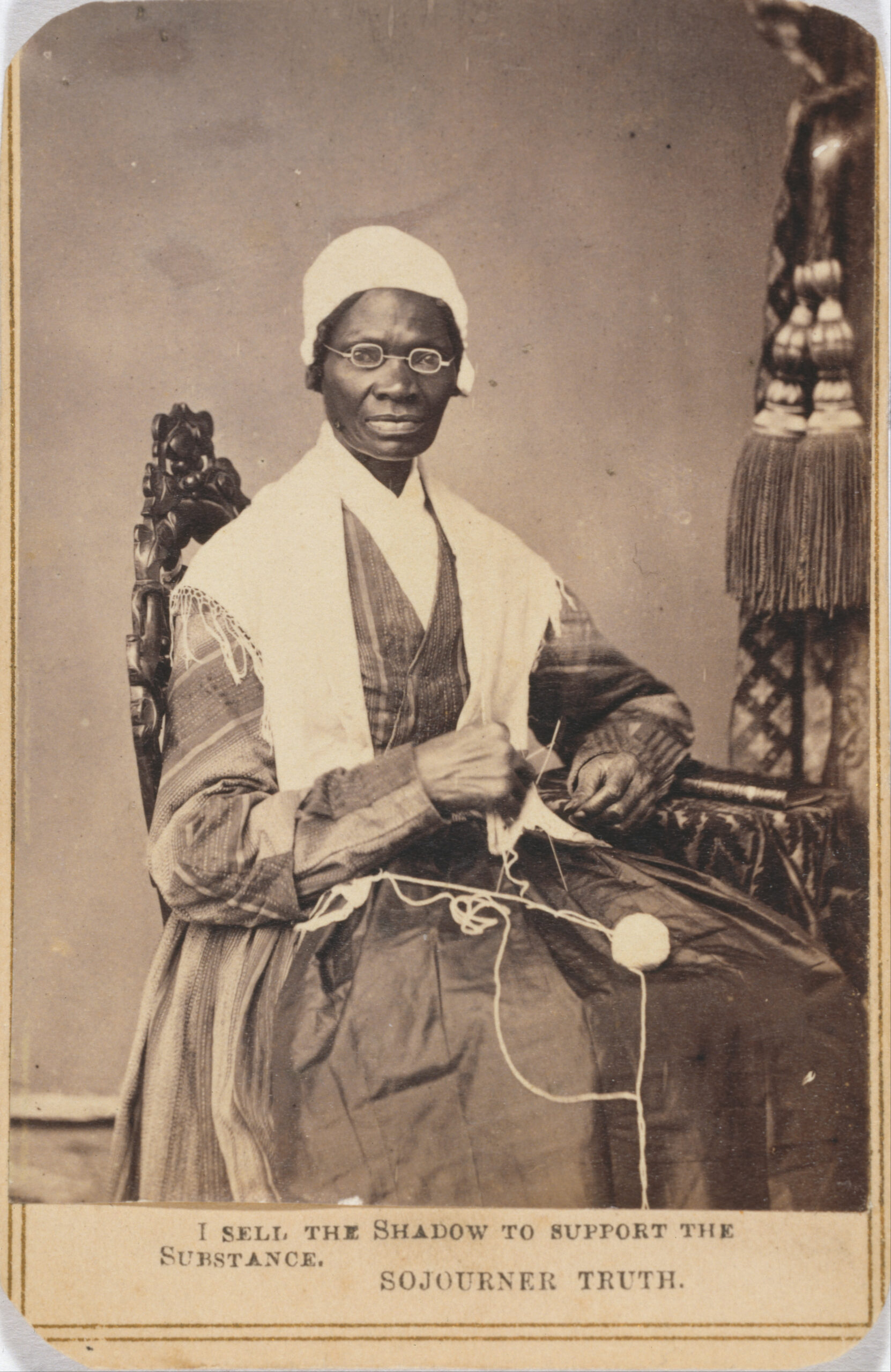

High school students are at an age where they are becoming increasingly aware of the social and political realities of the world, and beginning to understand how these connect to the injustices they see and experience in their own lives. This exercise from T&W teaching artist Bushra Rehman uses the revolutionary voice of Sojourner Truth in her 1851 “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech to show students how they can channel their passion and outrage into powerful persuasive essays. Included are links to audio, video, and historical resources that support and give context to the lesson.

How can one teach persuasive writing using poetry and revolutionary texts? It’s not as hard as it seems. For who is more adept at the art of persuasion than poets and revolutionaries? When I think of who convinced me to drop my fears and limitations, my boundaries, to pick up my anger or to set it down again, to love or to know when to cut love off, to stand for life even when it meant injury, I think of the poetic revolutionaries: Audre Lorde, Sojourner Truth, Harvey Milk, Malcolm X, and Assata Shakur.

When I learned the the art of persuasive writing, I was told to list three pieces of supportive evidence and three counter examples, as if by laying out a mathematical, rational structure I could sway the minds of my readers on some of the most controversial issues of our times. But it was never my mind that was most sensitive to persuasion, it was always my heart.

Hearing the word, “Ain’t” over and over in an English classroom has a thrill, and by the end, students are energized. I ask them if Truth has made her point clear. They insist she has.

When I am asked to teach persuasive writing to high school students, I take another path. I bring in the revolutionary words of Sojourner Truth’s speech “Ain’t I a Woman?” I know her words can reach the students and provide a brilliant example of how “style and content contribute to the power, persuasiveness, or beauty of a text.” [Language from the Common Core State Standards.] I begin by telling students Truth’s story. Born into slavery, she lived through enslavement’s deep cruelties, including the sale of her first four children in their infancy. At the age of 29, when Truth’s “owner” reneged on his promise to free her, she escaped with her infant daughter. Later in life, Truth received a spiritual message to travel the land and speak for freedom. She re-named herself Sojourner Truth and journeyed the country speaking on the rights of slaves and women, both free and in bondage.

Truth gave her “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech at a Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio, in 1851. At the time, a debate was raging about whether women “deserved” the right to vote. During the convention, a man stood up and voiced his opposition to women’s suffrage. He stated that women were too physically, thus mentally, weak to vote. At this point, Truth walked up to the podium and spoke. Even though the topic of the debate at hand was equality, the bill the Suffragists had proposed did not include voting rights for Black women. Truth, one of the only ex-slaves in the room, did not let this stop her. Truth’s ideas of freedom were vast.

At this point, I ask the students to read the speech aloud, round robin. I find it helpful to warn students that the language we are reading is from 1851. I allow them the option of saying “beep” if a word is uncomfortable or difficult for them to read.

Well, children, where there is so much racket there must be something out of kilter. I think that ‘twixt the negroes of the South and the women at the North, all talking about rights, the white men will be in a fix pretty soon. But what’s all this here talking about?

That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain’t I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain’t I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man—when I could get it—and bear the lash as well! And ain’t I a woman? I have borne 13 children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain’t I a woman?

Then they talk about this thing in the head; what’s this they call it? [member of audience whispers, “intellect”] That’s it, honey. What’s that got to do with women’s rights or negroes’ rights? If my cup won’t hold but a pint, and yours holds a quart, wouldn’t you be mean not to let me have my little half measure full?

Then that little man in black there, he says women can’t have as much rights as men, ’cause Christ wasn’t a woman! Where did your Christ come from? Where did your Christ come from? From God and a woman! Man had nothing to do with Him.

If the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down all alone, these women together ought to be able to turn it back, and get it right side up again! And now they is asking to do it, the men better let them.

Obliged to you for hearing me, and now old Sojourner ain’t got nothing more to say.

—Sojourner Truth

Hearing the word, “Ain’t” over and over in an English classroom has a thrill, and by the end, students are energized. I ask them if Truth has made her point clear. They insist she has. I ask, “What is this point?”

A student answers, “Women are not weak.”

I ask, “How does Truth persuade the audience to understand her point of view?” They call out:

“She repeated herself.”

“She talked like a regular person.”

“She showed her arms.”

“It’s like a poem.”

“She didn’t agree with their way of seeing women.”

And there it is, the brilliance of Truth’s art of persuasion. Truth turned the whole equation upside down by re-defining the central terms of the argument. What is a woman? Through her refutation of someone else’s definition of what it meant, Truth questioned not only the notion of womanhood but personhood at a time when slavery was still legally practiced in the United States.

While the speech is still fresh in my students’ minds, I create the bridge to their writing. I ask, “What are assumptions people make about you? What is it that people say you can’t do?”

The question is ripe and the energy is explosive. I fill the entire board with their answers and am barely able to keep up.

In one classroom the answers include:

“Can’t finish high school.”

“Can’t go to heaven.”

“Can’t be in love.”

“Can’t be gay.”

I follow up, “What would you say to someone if you were Truth and someone said you can’t go to heaven.”

The students shout out:

“Ain’t I human?”

“Ain’t I got a soul?”

“Ain’t a good person?”

“Now,” I tell students, “We’re going to write our own pieces of persuasive writing using Truth’s speech, but first, we will listen to Maya Angelou reading the speech for inspiration.” Many of the students know of Angelou and are excited to hear her voice and the persuasive power of Truth’s words. After we listen to Angelou, we begin writing.

The pieces the students wrote in this classroom were poetic and revolutionary. One student, who had been quiet through all of the first classes, wrote a thoughtful piece about being gay and denied entry into heaven:

“You say it’s an abomination to be gay. You say I can still be saved, or that I’m too far gone in my wicked ways. There’s no room in heaven for someone like me. But Ain’t I Human? . . . What makes you different from me? . . . We both have morals. We both love. Is that not human? . . . If God is only love, and love does not judge, doesn’t God love me? Doesn’t God not care that I’m gay? Doesn’t God not care that you’re a bigot? Aren’t we human?”

Another student wrote an amusing piece mocking assumptions about his background:

“That nerd over there says that all Asians are getting 2400 in SAT, and entering Princeton, and having the best boring jobs everywhere. Nobody ever finds me acing the SAT, or Ivy leagues, or gives me any doctor, lawyer, and engineering job. And Ain’t I Asian? Look at me! Look at my eyes! I have borne Kumon, and seen most all sold off to overly competitive wealthy parents, and when I cried out with my Asian’s shame, none but Buddha heard me! And Ain’t I Asian? . . . Then that little man in black, he says Asians can’t have as much creativity as them, ’cause free-thinking wasn’t for Asians! Where did your gunpowder come from? Where did your Nintendo come from? From God and Asians!”

One student wrote a gender-bending piece which upturned Sojourner’s original question. As a transgendered person, she asked, “Ain’t I a Woman?”

“Just because I may be a little different (special) or not seen as a biological woman . . . Ain’t I a Woman? I mean . . . I look like any one of your daughters, sisters, nieces, girlfriends, or mother . . . The way I dress, to the way I speak, to the way I brush my hair, to the way I strut down the street, you would see me as any other woman. So why look at me different? Know just because I’m sharing out to you the way I was born to the way I think . . . to the way I carry myself in the street. Let me just remind you I am a woman!”

At the end of the lesson, I was thrilled and humbled. The classroom I was in that day was in an under-resourced transfer school in New York City. There weren’t even enough desks and chairs for all the students. Classroom participation had always been a challenge, but Truth’s words had done what few teachers had been able to do. She had persuaded students to share what was on their minds, to speak up for themselves without fear, and to add their own unique voices to the ongoing conversation on freedom and equality in this country.

Rehman’s dark comedy, Corona, was chosen by the NY Public Library as one of its favorite books about NYC. She is co-editor of Colonize This! Young Women of Color on Today’s Feminism and author of the collection of poetry, Marianna’s Beauty Salon, described by Joseph O. Legaspi as “a love poem for Muslim girls, Queens, and immigrants making sense of their foreign home—and surviving.”

Her new novel, Roses, in the Mouth of a Lion, is a modern classic about what it means to be Muslim and queer in a Pakistani-American community.