“In a poem,” wrote the poet Maxine Kumin, “one can use the sense of place as an anchor for larger concerns, as a link between narrow details and global realities. Location is where we start from.” New York City, home of Teachers & Writers Collaborative, is at the same time a huge, thriving, world-class metropolis, and a place made up of unique small neighborhoods, cultural enclaves, parks, stores, and individuals. In 2008–2009, T&W sought to capture a sense of the countless wonderful details of life in the Big Apple in a collaborative poem written by the kids who live here. We sought contributions to this poem during more than seventy-five poetry workshops for children and teens held at arts and community-based organizations, public libraries, museums, and schools across the city’s five boroughs. The children and teens who participated ranged in age from 6 to 18 and came from all corners of the city, from midtown Manhattan to the far reaches of the outer boroughs.

To ensure the collaborative nature of the project, T&W teaching artist Melanie Maria Goodreaux created a curriculum framework that would serve as a guide to these poetry workshops. Goodreaux’s vision was to imagine the poem as a character, traveling through the city and observing all it has to offer. Writers from T&W used this framework to devise lesson plans for individual workshops where kids and teens wrote about the poem character’s explorations of New York City, with stops along the way capturing the sound, soul, and pulse of the Big Apple.

Following the workshops, Goodreaux read the thousands of poems created in the sessions and adapted the work into a single narrative. The result, A Poem as Big as New York City, was published by Universe Publishing, an Imprint of Rizzoli New York. In the book, the poem character travels not only to famous NYC landmarks such as the Empire State Building and the Times Square, but also to neighborhood corner stores; apartment window sills; and lush, green parks. The hard-cover children’s book features a foreword by Walter Dean Myers, the current national ambassador for young people’s literature, a three-time finalist for the National Book Award, and a T&W Board member; and illustrations by Masha D’yans.

While New York City offers an extraordinary range of sites, people, and experiences to inspire poetry, any city or town can launch a community project to engage kids in creating poems that share what is meaningful to them about the place they live. Here are some ideas to help you create a poem celebrating your own community.

Build Your Project Team

Like any community-wide project, creating and sharing poetry that melds the ideas of tens or hundreds or thousands of young people takes resources: locations for workshops and readings, teaching artists to lead workshops, money for publicity and printing. A community-wide poetry project offers the opportunity to connect with organizations you have collaborated with before while introducing your work to new supporters.

In thinking about possible partners, cast a broad net to be as inclusive as possible of your whole community. Establish a planning team of representatives from key constituencies, such as schools, libraries, museums, or youth-service agencies. Be sure to include at least one poet or writer who will be involved in leading your poetry workshops, and ask two or three young people to serve on the planning team. Involve individuals who will be able to help obtain the resources you’ll need for the project, including funding, media attention, and printing.

Define the Poetic Focus for Your Project

With a planning team in place, you will be ready to shape the focus for your poetry-writing workshops. The diversity of the people who live in and visit New York City, and the resulting mixture of cultures, made describing the poem’s journey around town a natural writing prompt for T&W’s workshops. Think together about what makes your community special and how you can translate that into a metaphor that will serve as a springboard for writing poetry. It could be another poem character, but it doesn’t have to be. Anything that is associated with where you live and that is meaningful to people in your area could provide an organizing framework for your poem project. Use the following questions to start brainstorming with your team:

- What is the physical landscape like here?

- What are key landmarks/buildings in the area?

- Did well-known historic events take place where we live?

- Who are noted residents—past and present—in the area?

- What kind of work is our city or town known for: manufacturing, agriculture, finance, health care?

- Is there something notable about travel in our area, such as scenic drives or the kinds of public transportation that people use?

- Are we seeing changes in the appearance or culture of the area: new buildings replacing old ones or vacant lots, arrival of immigrants from other parts of the world, closing of factories or other businesses that have reshaped the economy, urban expansion that has turned our historically rural area into a bedroom community?

- Do we want the young poets to focus on a small geographic area (the family farm, the urban block on which their apartment building sits) or a larger one (the town’s main street, a large metropolitan area)?

While you are making decisions about how to focus the prompts for your poetry-writing workshops, you should also be considering your desired project outcomes. Options include:

- Publishing an anthology of complete poems written in the program

- Taking lines or stanzas from individual poems and putting them together into one longer collaborative work

- Holding one or more public readings by children and teens who wrote poems during the project

- Creating a video with footage of places or activities referenced in the poems or animated verses with kids reading their poetry on the accompanying soundtrack

- Launching a website featuring poems written in your workshops, media showcasing the poetry, and/or an invitation to site visitors to submit poems about your community

Once your planning team has agreed on a focus for the poetry workshops and your anticipated outcomes, you will be able to draft the written materials that you’ll need to implement the project. Those materials include guidance for individuals who will lead poetry-writing sessions (including a description of the project’s focus and possible writing prompts); project descriptions for decision-makers at locations where you hope to hold workshops or readings; promotional materials to attract participants to poetry-writing sessions; permission forms for parents to approve use of their children’s writing and art work, as well as their photographs, in print or online publications; and letters or proposals requesting financial support for the project.

Start Writing!

With advance planning completed, you can turn to offering your poetry-writing workshops for young people in the community. T&W’s initial “Poem as Big as New York City” sessions were held in public libraries and other community centers during the summer months. Once school was back in session, the organization’s teaching artists devoted a day or two of their regular school-based residencies to asking students to write poems about New York. In addition to writing poems, you can also give kids the chance to illustrate their work, or invite children who don’t want to write to draw pictures in response to the writing prompts in the workshop.

If you have experienced teaching artists leading your poetry workshops, you will be able to give them the focus areas that you’ve established and let them create their own lesson plans. To help newer workshop leaders—or to inspire experienced teaching artists in search of new ideas—share the sample lesson plans down below and keep an eye on this page for additional teaching ideas.

If you expect to engage hundreds of kids in your workshops, it may not be realistic to include every piece of writing in a project publication. If that’s the case, be sure to let the young writers you work with know the ways in which their poetry may be shared, such as a print publication, a website, a reading, or a video. This will enable you to build excitement and interest while avoiding making promises you may not be able to keep.

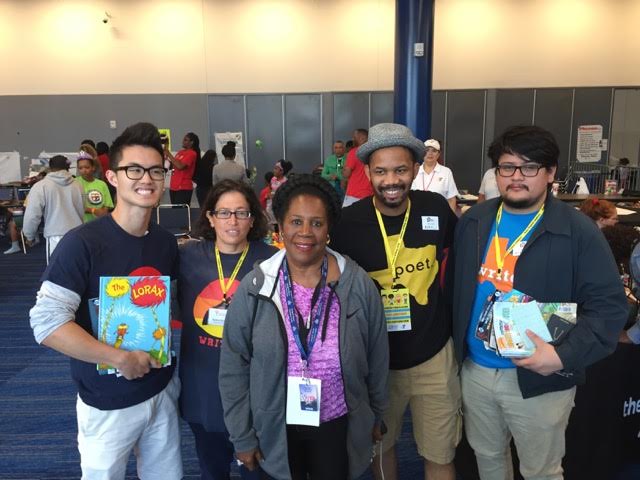

Finally, be sure to document the workshops, not only by collecting the poems that are written (along with the poets’ full names and contact information), but also by taking photos, videotaping sessions, and interviewing a few participants after several of the sessions about what the project means to them. The material you collect can be used in your project publication, on your website, in press releases, and in reports to funders and other project supporters.

Putting It All Together

With your workshops completed, it will be time to read all the poetry written in the project and decide how to put it all together. While you should have a vision of how you want to share the work with the community even before your first workshop, be open to adapting your plans based on how the project plays out and the opportunities that arise. For example, if you planned to adapt portions of poems into a single narrative but had fewer workshops than originally anticipated, you may decide that an anthology of complete poems is your best option. Perhaps a local cable TV station will hear about your project and want to turn what you thought would be a small reading for program participants’ friends and families into an on-air event.

A well-planned community poem project can accomplish many things: highlight the importance of arts education, draw attention and resources to the groups that provide it, foster collaboration among diverse local non-profit organizations, provide an opportunity for children and teens to be a part of a positive and creative community project.