Founded in 1967 as one of the first writers-in-the-schools programs, Teachers & Writers Collaborative once required its teaching artists to submit diaries of their experiences in the classroom. T&W’s founders believed, as we still do, that the knowledge and expertise of teaching artists would be valuable to teachers of creative writing across the country. Sharing this knowledge through our publications was a tenet of our work then, and we continue to publish the work of teaching artists today.

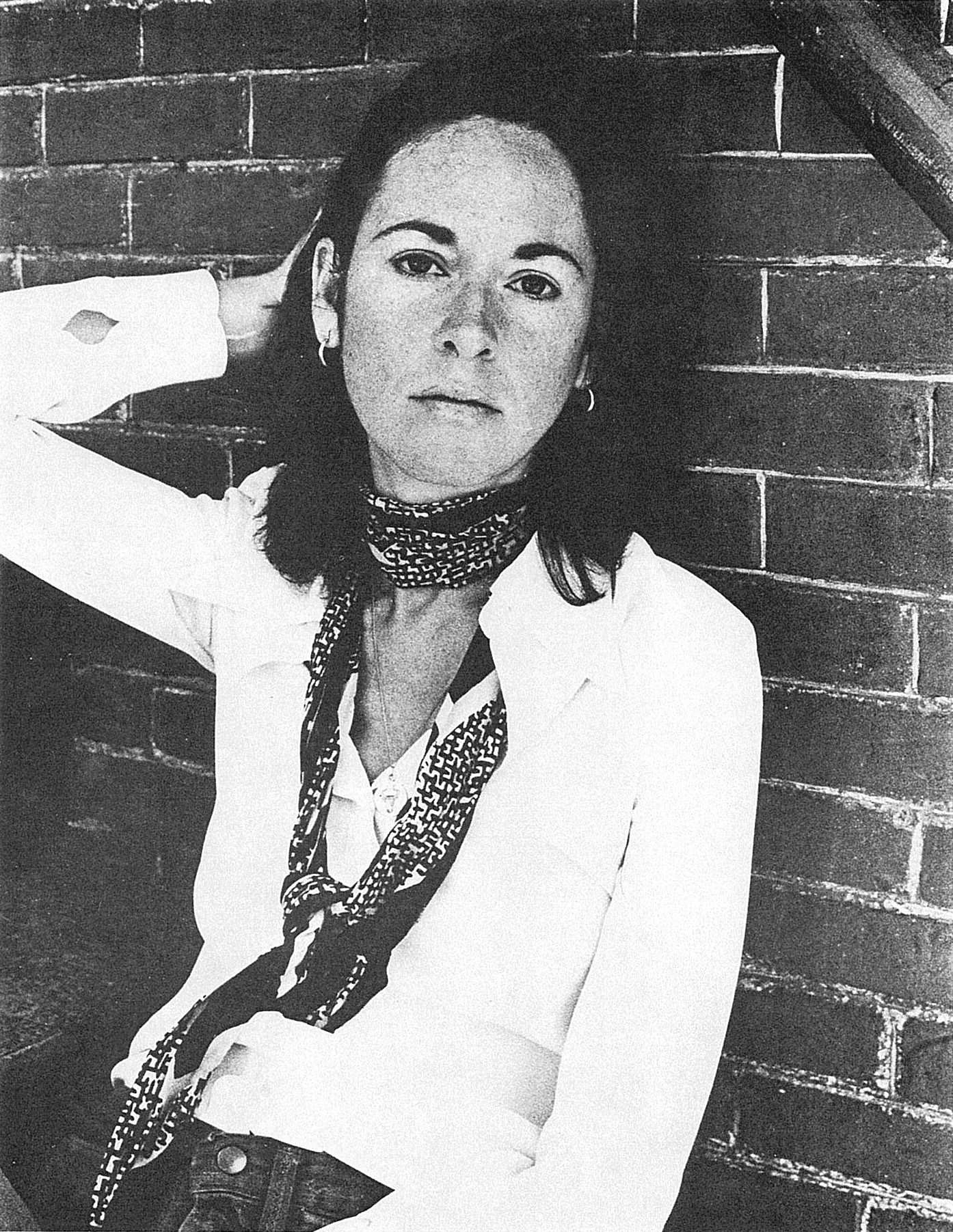

I first heard the news of Louise Glück’s passing in a Teachers & Writers Magazine editorial meeting. We were discussing the usual business when, upon seeing a notification, editor Matthew Burgess said: “Louise Glück died.” The gravity of this news was immediate. Glück, who received many of the highest literary honors, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2020, the National Book Critics Circle Award (1985), the Pulitzer Prize (1993), the National Book Award (2014), and served as Poet Laureate of the United States (2003–2004). Yet it was not her accolades that made the news of her passing as deeply felt by as many people as it was; it was how personal her work is to her readers. A fan myself, that famous couplet—“At the end of my suffering / there was a door.”—has lit my path in some of my darkest nights. It’s for this reason that, upon discovering her teaching diaries in the T&W archives a few months ago, I held them as carefully as if I had found a lost sacred text.

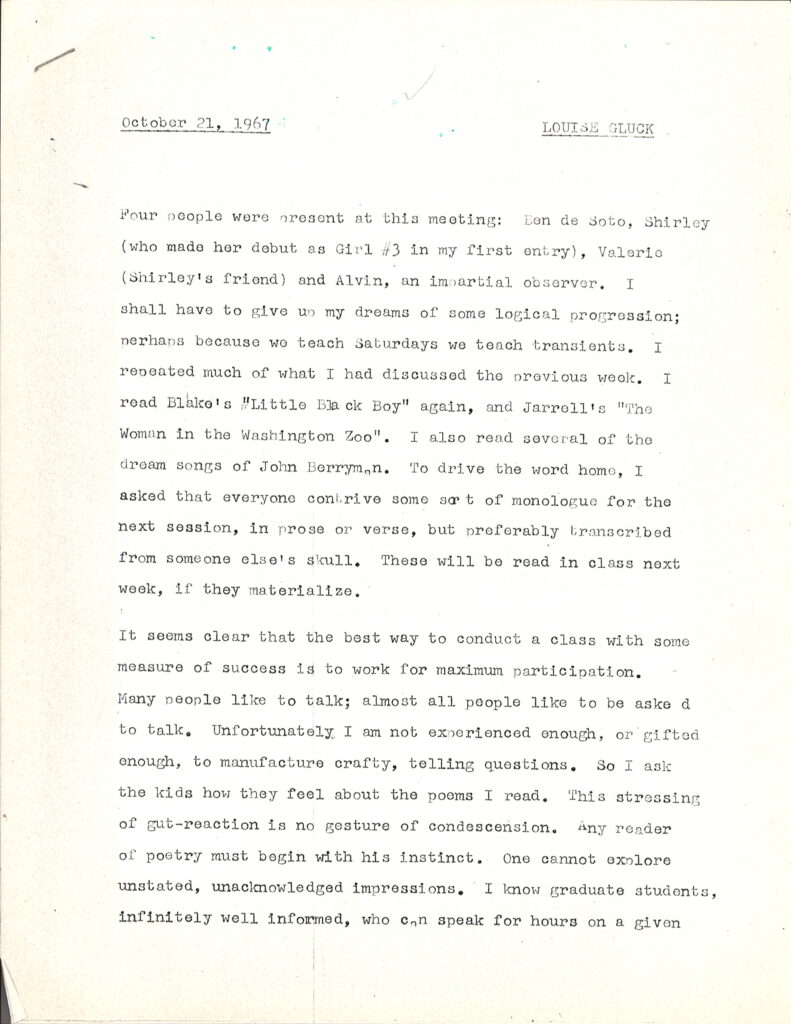

Typewritten on thin, yellowed paper, Glück’s entries begin in T&W’s inaugural year. Her entries are few (October 1967 – January 1968), though the first entry we have indicates that there were more. In them, one finds Glück’s discerning eye, conviction, and the infamous wit she would become known for. But they also reveal the humility of a young writer—24 years old, her first book had not yet been published—and the absorbent mind of a teacher in the making. Glück’s confession that she was “not experienced enough, or gifted enough, to manufacture crafty, telling questions” surprised me. I was not fortunate enough to know her, but she had developed, even from afar, such a wise, commanding presence that it was almost a shock to remember she, too, was once a young writer and teacher at the beginning of her powers.

In these entries, Glück describes trying to engage a sparse crowd of young students during weekend programming and discovering that one student defected to another writer’s room (imagine there not being a line to learn about writing from Louise Glück!). It seems she was eventually paired with the more experienced Peter Sourian, and she records her observations of his pedagogy as well.

With the entries we have chosen to share, I have attempted to mirror their typewritten state as closely as possible, choosing archival accuracy over house style or technical correctness (readers will surely notice the mostly absent umlaut from her surname). Some entries are shared in full and others have omissions indicated with bracketed ellipses [ . . . ]. Omissions were made for length and where the focus may have veered from pedagogical interest.

Glück’s teaching diaries were rich with wisdom and promise, and we share them now as a tribute to her singularly gifted mind. It is also our hope that by sharing her early teaching diaries, young teachers and writers will find something of themselves—their self-doubt and limitless potential—in a writer who, even in her lifetime, established herself as immortal.

Joshua Garcia

Managing Editor

Teachers & Writers Magazine

Early Teaching Diaries of Louise Glück

October 21, 1967

LOUISE GLUCKFour people were present at this meeting: Ben de Soto, Shirley (who made her debut as Girl #3 in my first entry), Valerie (Shirley’s friend) and Alvin, an impartial observer. I shall have to give up my dreams of some logical progression; perhaps because we teach Saturdays we teach transients. I repeated much of what I had discussed the previous week. I read Blake’s “Little Black Boy” again, and Jarrell’s “The Woman in the Washington Zoo”. I also read several of the dream songs of John Berryman. To drive the word home, I asked that everyone contrive some sort of monologue for the next session, in prose or verse, but preferably transcribed from someone else’s skull. These will be read in class next week, if they materialize.

It seems clear that the best way to conduct a class with some measure of success is to work for maximum participation. Many people like to talk; almost all people like to be asked to talk. Unfortunately I am not experienced enough, or gifted enough, to manufacture crafty, telling questions. So I ask the kids how they feel about the poems I read. This stressing of gut-reaction is no gesture of condescension. Any reader of poetry must begin with his instinct. One cannot explore unstated, unacknowledged impressions. I know graduate students, infinitely well informed, who can speak for hours on a given line, contriving elaborate cases for its excellence or its failure; they have their “yes” votes and “no” votes constantly on tap. And they have no idea at all what they think. I will not be party to this sort of bravura.

The Blake went over best. Everyone liked it; Alvin was particularly articulate. The Jarrell poem, with its Roman senate sentences – those single breaths bloated into paragraphs – is perhaps difficult for them to grasp at reading. I went through the tricky places slowly. No one knew quite what to make of the Berryman.

I ended with Ben’s poem. The girls had heard it already. They are unwilling to criticize each other. It is my hope that these children will eventually find a security that allows for really strenuous discussion. But it’s a question of atmosphere as well. The atmosphere in which useful, fierce criticism flourishes is one of mutual respect. We must effect it.

NOVEMBER 18, 1967

LOUISE GLUCKValerie, who is winning all points for promptness & loyalty, was the only one of my assigned four who showed up. She did not, however, show up with her assignment (now in its second week). She said she had to finish a book for school. The book was To Kill a Mockingbird. I haven’t read it; I could not respond to Valerie’s “Do you understand it?” I might not have, even if I knew the book. I can conceive of Valerie’s accepting my impressions as fact, or accepting them as better than her own, at any rate. And she could set my views down in her paper with no hesitation. What if she still got a low grade?

We talked for a bit about her school. She seemed quite open & somewhat garrulous. She claimed to find her teachers uniformly adequate. I asked if she had any particular ambitions; she replied that she wanted to be an executive secretary. We talked for a bit about executive secretaries.

I had brought a volume of Emily Dickinson. We read several poems – Valerie was more interested in these than in anything I have brought in to date. She said she didn’t understand them, which claim I find most reasonable. Mid-way through our readings one of her friends walked by, a boy who had apparently been in one of the upstairs groups. He mocked Dickinson; I was afraid his inappropriate generalizations would make it impossible for Valerie to stay interested. But she did.

I asked that she try the dinner table assignment, and also that she bring in a paper she had written on success for her English teacher. I should add that I have not reproduced any of the critical conversation because the comments were invariably my own. [. . .]

Hell, she shows up. That in itself is quite a virtue these days.

LOUISE GLUCK

DECEMBER 9, 1967I joined Peter Sourian in the upper regions. Now I see what this sort of class can be. There were enough people – about ten, I should say – to turn the problem from drumming up comment to controlling chaos. It is easier to control chaos. Or channel abundance. As I have pointed out before. Peter was extremely gracious.

It seems that it is to his classes that Desiree has disappeared. I am obliged to admit a hurt. We spent much of the class time discussing a poem she had written. The discussion lead to speculation & dogma: one line in the poem was vastly better than the poem. The line went “We are pushed together, but not the right we”. The rest of the piece was not so telling; it was vague, general, evasive. The speculation that followed the reading was an attempt to articulate the difference between that true line & those preceding & following. The dogma drawn out of the old stew pot of literature for this occasion was the one stressing the force of the particular. We spent several minutes underlining that phrase.

Peter went on to speak about the search for story material. He did research on a quiet boy. He asked the boy where he had eaten his dinner the night before. And what it was. He’d eaten at home, with his father, in the living room. They’d had spaghetti. (He answered the questions with a certain embarrassment; he seemed unconvinced that this scraping would yield ore.) Peter asked, finally, if the spaghetti had been good. The witness grinned briefly. He said it was awful. He said his mother couldn’t cook anything. Peter said, “Did you tell her?” “Tell her what?” “That her spaghetti was awful?”

He hadn’t. But he could see, after some more talk, that the incident had interest, that something could be made of the enraged silence in which he & his father stuffed it down.

It was an impressive hour. I learned. Ben Soto, who has borrowed my Antiworlds, failed to show.

January 13, 1968

Louise GlückPeter Sourian is a remarkable teacher. I should like to say that I learn by watching him. But I wonder if it isn’t a good deal more basic: those qualities which seem to make his presence so effective among adolescents – a kind of esprit, energy, evident concern – are not qualities which I stock. I suppose the point is that he cares and it shows. I don’t fake. And I don’t really care as he seems to. I do make myself useful; I pay attention, I comment when moved, when not moved and generally try. I have to. I have no rapport to fall back on.

A boy named Eddie handed in a story he had done which Peter thought constituted a breakthrough. It seems Eddie had refused consistently to deal with anything of import, to confront his past or his feelings about his past. He wrote about leaving a reform school. The episode was written quite badly, and it was not necessary to be silent about its flaws. The atmosphere of this class is so really loving that one can say the truth and watch it swallowed whole; we are not obliged to lie tenderly. In spite of expositional flaws Eddie’s piece had great interest & force, & honesty. He looked away or down when it was read. He knew what was in the lines.

LOUISE GLUCK

SATURDAY, JANUARY 27, 1968Today was poetry day. As a special treat we celebrated with undiluted Gluck. In point of fact, that arrangement was less a product of hubris than a lack of time. You up there are living to hear a poet complaining of the sparcity of machines. Indeed.

Peter had asked me to be responsible for the poems to be read and discussed. He suggested rather strongly that my own work be included in the harvesting. Unfortunately, my schedule was abruptly adjusted around mid-week; the Xerox I had expected to use was not to be available. In the end I simply gathered in those pieces of my own making already reproduced. I passed out four poems.

No one was awfully interested. Eddie had come in with a disturbing story: Lydia had run away. [. . .]

Peter made an effort to direct the group through two of the poems. They are less at ease with me than with him, with poetry than with prose. I rather think my presence on this particular morning acted to inhibit.

LOUISE GLUCK

March 2, 1968Much of the hour was given to discussion of Joe Barthell’s induction. The group was small: Eddie was there first, then Peter Kelly. At about quarter to one – we had begun at eleven – Lydia arrived. She’d been on an errand.

[. . .]

The literary discussion centered on the re-print of my diary entry and on a poem of Eddie’s. Peter called the attention of the class to the diary which he called an example of good writing. Naturally I declined to comment. Peter Kelly had not arrived. Eddie was forced to react for the whole crew. He tried to look concerned. No wonder he doesn’t want to go to school. His poem was interesting. It was extremely uneven, but one can predict that. Effective phrases are constantly juxtaposed with cliches. But what is important to state is that Eddie’s poem, like his story, was strongly felt.

[. . .]

Learn More about Louise Glück

• Louise Glück – The Poetry Foundation

• Louise Glück – American Academy of Poets

• “Louise Glück Remembered by Writers” – The New Yorker

• “Louise Glück: Revenge Against Circumstance” – What It Takes podcast

Teachers & Writers Magazine is published by Teachers & Writers Collaborative as a resource for teaching the art of writing to people of all ages. The online magazine presents a wide range of ideas and approaches, as well as lively explorations of T&W’s mission to celebrate the imagination and create greater equity in and through the literary arts.