“Can’t the dream also be used in solving the fundamental questions of life?”

—André Breton, Manifesto of Surrealism (1924)

Dreams are the poems that everyone writes. Available to the literate and illiterate, to the successful and to the outcast, dreams by their nature suggest that everyone has the capacity for poetry. As Freud pointed out, dreams are “represented symbolically by means of similes and metaphors, in images resembling those of poetic speech.” André Breton loved to talk about dreams not only because of the way their leaps in logic and strange juxtapositions subvert conventional ways of thinking, but also because they bolstered his egalitarian approach to literature. It may not be strictly logical, but there’s something appealing about the faux proof his thinking suggests: 1) Everybody dreams.2) Dreams are like poems. 3) Therefore, everyone is a poet.

Because the similarities between dreaming and writing poetry can make poetry seem more accessible to students who might be skeptical, I usually start my teaching residencies in New York City public schools with a lesson on dreams. “How is a dream like a poem?” I’ll ask my students. They will often respond with “Anything can happen,” “They are weird,” or, “They don’t make sense.” I like this last answer because it creates an opportunity for us to have a conversation about different ways of “making sense.” Beginning writers sometimes focus so much on trying to “make sense” that they lose sight of what I believe is most important in writing poetry: the feel of vowels and consonants in one’s mouth and the multi-sensory images that words make manifest. Poetry invites us to relinquish our desire to “make sense” and to think about the other possibilities and qualities of language.

When I was in middle school, a camp counselor (who happened to be a T&W teaching artist during the school year) introduced me to the Chilean physicist-poet Nicanor Parra’s list of dreams. Three decades later, I still return to this straightforward list poem of images from real or imagined dreams. In the English translation by Miller Williams, the poem, titled “Dreams,” begins:

I dream of a table and a chair.

I dream I’m turning over a car.

I dream I’m filming a movie.

Before I ask my students to write their own list poems, we talk about the different meanings of the word “dream.” I tell them that sometimes a dream is another way of saying “a wish,” but in Parra’s poem, each line is clearly a sleeping dream, as opposed to a hope. I ask my students to point out lines in Parra’s poem that create a picture in their mind. In his poem, the images are primarily visual, but we talk about how sometimes we hear or taste things in dreams. Together we write a group list of dreams, which gives me an opportunity to challenge them to add details to their lines. Then the students get to work on their own poems, following the dream list model.

For a long time, I had been looking for another list poem about dreams to use as a model for a follow-up lesson I could teach after having students write their dream poems inspired by Parra. I recently discovered this witty poem by Elaine Equi from her book Click and Clone. I find myself returning to her work often when I am thinking of lesson ideas because her poems often start with an interesting and fun concept that students could try their hands at.

Everybody Has Dreams

Last night, the cook dreamt a giant mouth dribbling blood

or ketchup. He has trouble relating to women.The woman in the beige pantsuit dreamt of a computer that

transports objects into the future.The woman by the window was a little girl holding her mother’s

hand.The guy near the door followed a melody into a forest.

The busboy was driving a sports car fast.

The skinny girl was a military general in a country ruled by a giant

inflatable cat.The waitress murdered somebody. Even now, she looks guiltily

over her shoulder as she wipes the silverware clean.

I like the way the speaker of this poem has the ability to know what everyone around her is thinking. I tell my younger students that this poem suggests that being a poet gives you magical powers. The poem is a model of the power of the imagination in daily life. After we read it aloud, I ask my students to imagine that they, too, have the ability to know what strangers are thinking, and then introduce the lesson below, in which I ask them to write a poem that travels into the heads of multiple characters. I have taught this lesson—with variations—to fifth-graders in Brooklyn, and to advanced high school students studying poetry at Sarah Lawrence College, as well as to my post-graduate level private workshop.

Photograph & Dreams Lesson

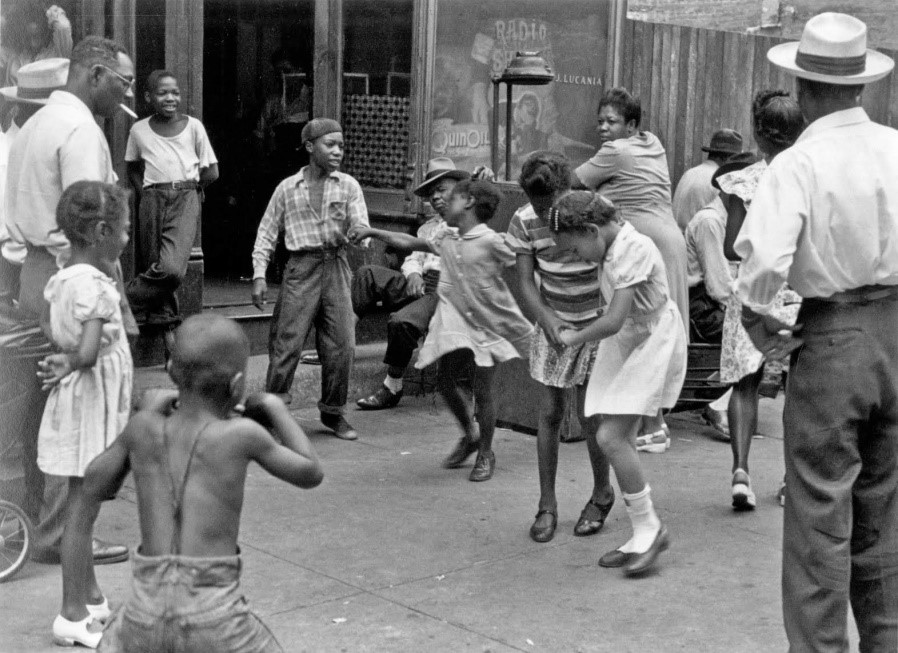

- I start by projecting a photograph on the board or handing out copies to share. When I taught this lesson to fifth-graders, I used Helen Levitt’s photograph of children dancing in Harlem and projected it on the board.

- Once they’ve had a chance to study the photo, I ask my students to tell the class what they think the various people in the scene might be dreaming. I invite them to use their imaginations to make up the dreams and remind them that in the world of a poem, even objects or animals can dream.

Or, I might ask them to tell us the secrets or thoughts of the people in the photo. What are they thinking about, but can’t say?

- Next, I ask them to give me lines about various people in the picture. These are the sort of questions I use to get the students started:

What did the man in the hat dream last night?

What about the girl with socks and dancing shoes?

Who else do you see in this picture?

How do you want to describe them?

Then, to follow up:

What do you think he dreamed?

What is she thinking about?

- If, in response to these questions, students say something like, “The boy with the striped shirt wants to be at home,” I follow up by asking, “What do you think he would want to be doing at home? Can you use your words to paint a picture of what in particular he is imagining?”

- After I compile their suggestions into a class poem, and write it on the board, I give each student a printout of a different photograph I found online and tell them to try the activity on their own. (For my fifth-grade class, I found the photographs by Googling “Harlem street photography of children” and “New York street photography.”)

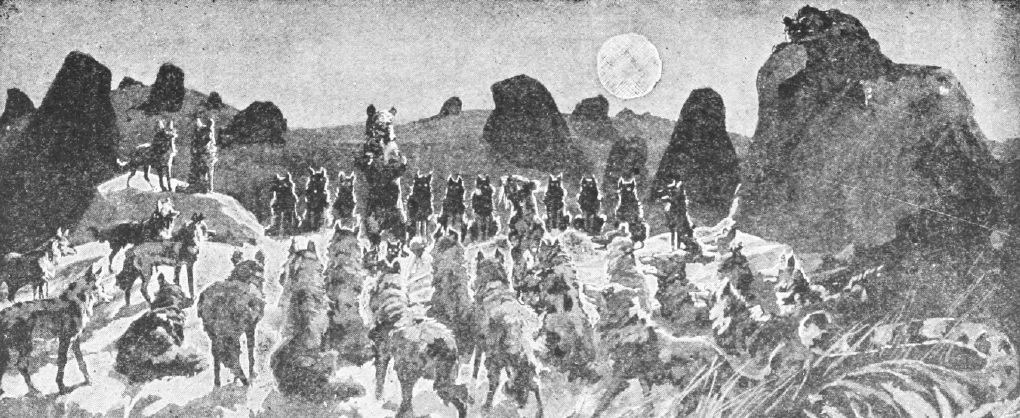

- For the high school students last summer, I led this exercise the day the class went on a trip to the Whitney Museum, where an exhibit by the documentary photographer Danny Lyon was being shown. Instead of doing a group poem, I projected Lyon’s image of an Occupy protest on the board. (I didn’t give the students the context beforehand because I wanted to leave the image open to interpretation.) I then had them each write their own poem inspired by this image, using Equi’s poem as starting point.

I like using this photograph with more advanced students because it brings the social and political into what at first seems like a whimsical exercise. I was happy to see that many of my high school students took my suggestion to imagine what the objects and animals have dreamt, and not just the humans.

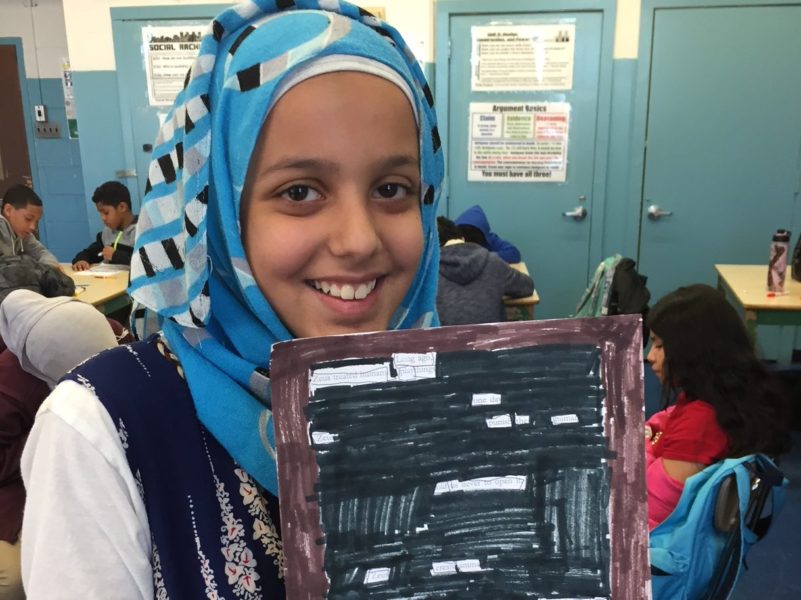

Here’s a poem by a student in the fifth-grade class in Brooklyn. She wrote it in response to an image of an assortment of people of different ages, races, and backgrounds in New York City’s Herald Square.

Dreams

The woman in the black dress

dreams that she is going

to the mall on a skateboard,

flying through the aisles

in the mall snatching clothes

and walking out the store

without paying for anything.—Nasirah

Nasirah creates an interesting ambiguity in her poem by combining the two meanings of dreams. Did the woman actually dream this scene, or is this her secret desire? I love the surprising contrast between the black dress (a symbol of mature elegance) and the skateboard (a marker of youthful exuberance), and I also love the word “snatching,” which is such a specific verb and is almost onomatopoeia for the sound of enthusiastic grabbing.

Here’s a poem by one of my high school students this summer:

Nighttime’s Reverie

The policeman, he honestly wasn’t honest.

Lying to him was a game,

One that kept him up at night.The one with the Nike shoes, she had a nightmare,

The type that wakes you up in a cold sweat,

It was going to school 24/7.The anonymous man, he dreamed he was famous,

but he could never remove his mask.If he wore boots, the man in the flannel could’ve

been a cowboy but he’ll continue to unconsciously

hope for a new stuffed animal.Her.

Yes, her.

The one with the ponytail, she dreamed of a whole new world,

one where her dog might reply when she asks a question,

or her friends might laugh when she made a joke.The man in the suit, he closed his eyes and hoped for something small,

wrapped in the exact same manner as a large burrito would be—

the large, warm burrito would be named Gabriel, or maybe Michael,

but just maybe the tiny bundle would be named Ruth.The four footed ones were different.

They dreamt

and dreamt

like no other

they saw. They saw

what is,

what was,

and what will be.They are always sleeping.

—Maria Castellanos

I like the way each image in Maria’s poem perfectly captures a moment of pathos, and the animals in the poem possess a wisdom the humans can only long for. I imagine Breton would approve of her vision of sleep as the source of peace and wisdom.

Joanna Fuhrman is an Assistant Teaching Professor in Creative Writing at Rutgers University and the author of seven books of poetry, including To a New Era (Hanging Loose Press, 2021) and the forthcoming Data Mind (Curbstone/Northwestern University Press, 2024). Fuhrman's poems have appeared in Best American Poetry 2023, The Pushcart Prize anthology, The Academy of American Poets' Poem-a-Day, and The Slowdown podcast. She first published with Hanging Loose Press as a teenager and became a co-editor in 2022.