Bechtel Prize Judge Garth Greenwell selected Abriana Jetté’s essay “Flexing Our Rhyming Muscles: Introducing the Ghazal” as the 2024 Bechtel Prize winner. The Bechtel Prize is awarded for an essay describing a creative writing teaching experience, project, or activity that demonstrates innovation in creative writing instruction.

Of Jetté’s essay, Greenwell shared: “This essay brings us excitingly close to particular moments of writing while also immersing us in a sophisticated and appealing philosophy of the creative act. Along with the writer’s students, readers are lured from a space of seemingly chaotic play to an intricate and richly embedded (in history, in place) understanding of form. The essay beautifully dramatizes the dialectic of freedom and discipline that animates all art.”

The Bechtel Prize is named for Louise Seaman Bechtel, who was an editor, author, collector of children’s books, and teacher. She was the first person to head a juvenile book department at an American publishing house. As such, she took children’s literature seriously, helped establish the field, and was a tireless advocate for the importance of literature in kids’ lives.This award honors her legacy. Learn more about the Bechtel Prize here.

It is the Wednesday after Thanksgiving, and I am in a silly mood as I laugh to myself on my walk to class. It is the Wednesday after Thanksgiving, which means over 13 weeks have already passed. The end of the semester draws near.

It’s the Wednesday after Thanksgiving, so in less than two weeks, my students need to submit their final project, a chapbook of 15-20 poems they’ve composed this semester. I’m in a silly mood, laughing to myself about nothing while I walk to the classroom. I know they need to write, make that page requirement. We’ll write together, I figure, as I walk to class. We’ll make it silly.

I open the door, walk to the desk at the front of the room. The hour shifts. The students settle. We offer our ritualistic hellos. They look at me to begin. I begin:

“Write down words or sounds that rhyme with your name. As many as you can.” It’s one of the simplest ways I’ve begun class, and the simplicity begs questions.

“What do you mean, rhymes with our name? First name? Full name? Nickname? Surname?” they ask.

“Whatever,” I answer. “Whatever rhymes you can find.”

“Write down words or sounds that rhyme with your name. As many as you can.” It’s one of the simplest ways I’ve begun class, and the simplicity begs questions.

Some open their laptops right away. Some stare into the center of the classroom, at the abyss of emptiness our quasi-horse-shoe-shaped desks create.

“Here, I’ll model some ideas for you,” and I start the same way I start any poem, with the alphabet. “I’ve been doing this forever,” I confess, listing the alphabet as my header, going through each letter until some soundscape clicks.

“You could just go to a rhyme dictionary online,” one retorts.

“You absolutely could. But there was no internet like that when I was younger,” I say, dating myself, and continue to model the strategy.

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

“So most people call me (Name Removed),” So I start there. (Name Removed). Babe. Brave Blade. Cave. Claim. Cage. Dave. E? . . . eh, hmm, when it gets tricky I move on to the next.”

One of them hollers “vape!” and some roll their eyes. I stop and say, “Get it?” They offer a collective nod to signal yes, they do get it, and they begin to do it, list words or phrases that rhyme with their name.

After a few minutes I stop them, all 20. Twenty poets huddled in a horseshoe on a cold, late November afternoon, or morning, depending on what you think about the 11:00 hour. They come, each class, these 20 poets, the majority of whom are not English majors. They do the reading. The writing. They’re really good students. After a few minutes, I ask them to awkwardly stare at me when they have reached a minimum of eight rhymes. Sooner then later, they all start to stare.

“OK. Now ask a question. Any question. Doesn’t have to be philosophical. Can be like ‘What’s for dinner?’ or ‘Where did I park my car?’ or maybe even ‘What type of shoes are those?’”

They write their question. Another pause comes, and I ask them to turn and talk, which means turn to the person to their right or left and share with them what they wrote. Some of them share the question with the whole group before we get back to the exercise.

“OK. Now answer that question with an anti-answer.”

That’s our job. To weave. Piece together. Discover the connections. The poem.

We use this prefix often. We write anti-sonnets and create anti-titles and so when I say anti-answer they know that I mean an answer to the question you typically would not offer. If the question posed is “Should I cut my hair?”, the anti-answer might be “Don’t forget to buy lettuce.” It is disconnected, so to speak. But that’s our job. To weave. Piece together. Discover the connections. The poem.

“OK! Are we all together? We’ve rhymed with our name. We’ve asked a question. We’ve written an anti-answer.” I offer a few collective moments for those who are still typing.

“Next, write a declarative statement. Begin it with I am _______, then fill in the blank. I am on campus. I am beyond confused. I am lonely. I am despondent. I am in need of coffee. Whatever.” A few minutes fly. The whole time, I’m playing around, too. Feeling silly. Rhyming with (Name Removed). Asking questions that refuse answers.

I gather them together again. I ask “Are you ready?” They nod their heads. I say, “I can’t hear you!” as if we are on a gameshow.

“Are you ready to transform these lines?” I say again but with more enthusiasm, voracity.

“Yes,” a few of them say loud enough for me to hear.

I give them the following directions, and I offer appropriate time in between each step. I encourage them to reread the lines with each new step, to add or delete or revise accordingly. All together this part takes around 20 minutes. The directions are as follows:

- Move your question to the first line. Begin your poem with the question.

- Write a rhyming line. Break the stanza after this line. The poem will be in rhyming couplets.

- Add a moment of epizeuxis. Make a rhyme scheme that echoes the sound of your name. (Choose from your word list.)

- Write until you get to the 4th or 5th line of the poem, depending on what you are doing with linebreaks. Try to work towards a minor rhyme sound. Make the 4th or 5th line your anti-answer to the question posed in the first line.

- Write your declarative statement.

- Now answer the question you posed in the first line with a real, honest answer. Include the rhyme sound of your name. Modify lines accordingly.

- Write a final line/couplet. Make the last word of that final line, make the last line of the poem, your name.

They do as told when told to do it. Some eyes become dizzy throughout, rearranging, rethinking, busy with the work of the poet. Some eyes are doubtful. What’s the point here? What are we doing? But they do it anyway. When the music of their keyboards commences, they look at me again, the same way they did close to an hour ago when class first began.

I know what they want, why they’re looking. They want to know what they’ve made, the reason for the making. But I am feeling silly. So I hold off on the giving.

“Now remember, this isn’t finished yet. It’s not perfect. But it’s playful, and it’s something. And it’s got your name in it! How fun!” I ask them to turn to the person they spoke with earlier and share what they’ve created.

They take a few minutes, share their work. Afterwards, the poetic urge within them begins to rise. From the horseshoe whispers of: “Are we going to revise this?”/ “Can we work on this some more?”/ “Does this really have to rhyme?”

They think I’m being silly, trying to level with them. But I’m being earnest. Sometimes I take poetry too seriously.

“You know,” I tell them, “sometimes I stop myself from writing because I only have 30 minutes, or the laundry needs to be done, or I’d rather write an email, or the idea isn’t fully developed. Sometimes I give myself any excuse not to write a poem.” They laugh. They think I’m being silly, trying to level with them. But I’m being earnest. Sometimes I take poetry too seriously.

I tell them about a poet I know who would write 15 minute poems on the notes of her iPhone. I always envied that, I told them. Sometimes, I take poetry too seriously, I tell them, I tell myself, again. “Today we’re going to be like O’Hara. Write our poems quickly and let them be as they are. Maybe drink a Coke!” (I am the only one who chuckles.)

Before today, before this Wednesday after Thanksgiving, it was the Wednesday before Thanksgiving. During that session, we worked on internal rhymes, and I promised it would lead to ghazals.

Doubt grows on their faces. Eyebrows raise. Lips curl. After 12 weeks, they know me better. Why was I sticking with rhymes as rhymes as rhymes? What was this nonsense of leaving the poem as is? Where was the form—FORM!—they had all come to expect?

I give them 10 seconds. Maybe 15. I let them rest in discomfort.

“Or . . . ,” I say.

Together, they exhale.

Another option.

I tell them when they’re home, when they leave me, to revisit what they have written. I offer this advice while simultaneously distributing a worksheet on the ghazal, which is a photocopy of the first two pages of the chapter on pantoums and ghazals from Wendy Bishop’s Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Poem, one of my all-time favorite poetry anthologies, a description of the form from the Poetry Foundation, and my own paraphrasing of these definitions and descriptions. My notes remind them that the form is not natural to the English language, but to Arabic, and so there is some maneuvering we might experience in terms of end-stops and caesuras and ensuring rhythms and cohesion from one couplet to the next. I mention how contemporary perceptions of love may differ from seventh century Arabia, when the form began to come into fashion, and to lean towards their own understanding of how a love poem might behave, if they are interested in sticking to traditional themes.

I tell them what they already know, that they’ve got the bare bones. Maybe some of their lines do not concern love. Maybe some are downright silly. Come to think of it, maybe they’ve written anti-ghazals. But here we are, this Wednesday after Thanksgiving, building something together. I’ve given them form. What they’re working towards is the poem.

When class ends, when they leave me, when they come back to those lines, that’s when they start to figure out the difference.

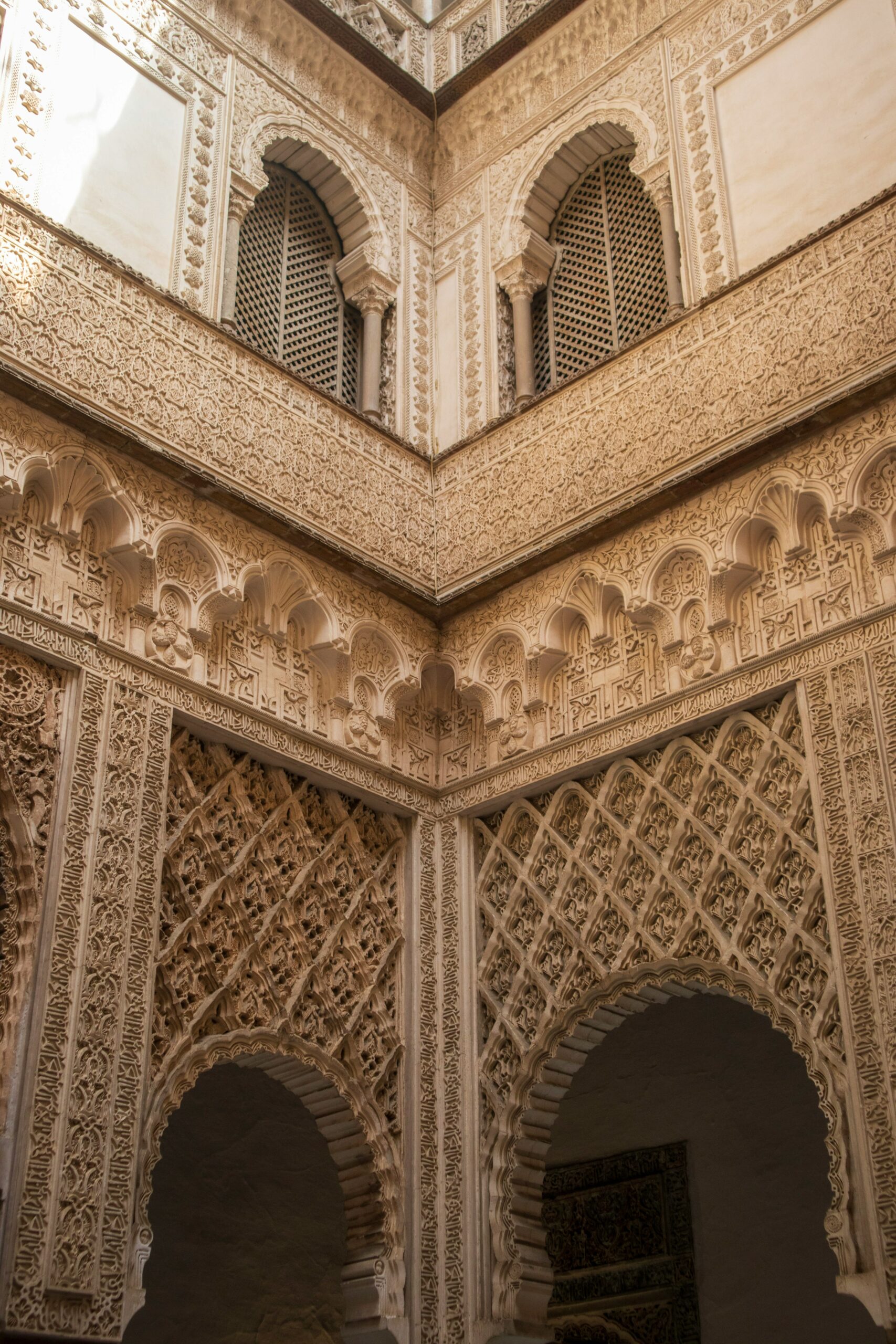

Featured photo by Clark Van Der Beken on Unsplash.

Born and raised in Brooklyn, New York, Abriana Jetté is a poet, essayist, editor, and educator. Her writing has been featured in Best New Poets, Poetry New Zealand, River Teeth, The Moth, Plume, and other places. She teaches various writing courses for Kean University, where she also leads the Common Read program.