If the beats were made of meat, then they would have to be mince is one of the many fine lines from “Rock the Bells” by L.L. Cool J—a song on his seminal record, Radio, released in 1985. It’s a shout-out to L.L.’s D.J. Cut Creator, but, for me, it marks an important moment in my on-going love affair with language. A 16-year-old, growing up in downtown New York, during those nascent days of hip-hop and a thriving punk scene, I spent most weekends traipsing around bars and clubs. Living with a single dad who worked nights, I also spent a lot of my time unsupervised and sitting on stoops. Like many city kids, I had a handful of favorite spots which my friends and I used like open-air living rooms. Each set of stairs had its own vibe. Each threshold offered a different view of street life. Everything I saw and heard contained some kind of lesson that would ultimately constitute a crucial part of my education. “Rock the Bells” is but one cut from the soundtrack of my moody, unruly adolescence.

It wasn’t until years later—when I realized I wanted to be a poet—that I fully appreciated how much the music I listened to while hanging out or biking around with my Walkman had informed my love of language. L.L. Cool J’s playful, boastful, beautifully balanced lyrics hooked me from the get-go. I loved singles like “Rock the Bells” and “I Need a Beat” for their quick-witted couplets, juxtaposition of images, and alliteration, for their humor and surprising allusions. Even pedestrian rhymes—like “was” and “cuz”—were buoyed by a driving beat that kept me returning to certain tracks over and over. To this day, I joke: Ask me what I had for dinner last night—I can barely remember. Ask me to recite “I Can’t Live Without My Radio”? That I can do.

Music by artists like L.L. Cool J, KRS-1, David Bowie, and groups like Sugar Hill Gang, Run DMC, and The Clash was just as instructive to me as anything I was learning in school. While I may have been a teenager inclined to skip class, I was also a teenager inclined to read. I read anything and everything from F. Scott Fitzgerald to Marguerite Duras to Maxine Hong Kingston and James Baldwin. It was my deep love of reading—fused with the rambunctious self-expression and rough lyricism of early hip-hop and punk rock—that primed my ear for poetry.

By the time I was 19, I was ready to receive lines like Walt Whitman’s:

Do I contradict myself?

—from “Song of Myself, 51“

Very well then, I contradict myself

I am large

I contain multitudes.

Worlds apart, Whitman and Cool J were—to my mind—working from a similar artistic impulse fueled by musicality, lyricism,and vigorous assertion of the self. It was the gift of receiving messages from all corners of all the cultures that helped me recognize this and also validated my own sense of amalgamation.

Another gift came in the form of Margaret Edwards, a professor at the University of Vermont, whose 20th-century poetry course I took during my senior year. Professor Edwards—who swept in on the first day of class wearing a black cape, riding boots, and wispy silver hair pinned back à la Emily Dickinson. Professor Edwards—who spoke of herself in the third person as she explicated the stringent requirements for success in her class—which included using a fresh ink cartridge to print our papers so she wouldn’t have to strain her eyes. With a Southern drawl and a lucid stare, Edwards made it clear she didn’t suffer fools. While her formidable bearing scared off a few students—there were a couple of empty seats the following week—she fascinated me. And so did the poetry.

It was the sense of real-world relevance and immediacy she created around the poets and their poetry that made the poems feel as alive to me as music did.

Under Edwards’s guidance, we dug into poems by Frank O’Hara, Gwendolyn Brooks, John Berryman, Sylvia Plath, Sharon Olds, Galway Kinnell, and others. Peppering her lectures with personal anecdotes, Edwards created context for their work by sharing her own experiences of the era. It was the sense of real-world relevance and immediacy she created around the poets and their poetry that made the poems feel as alive to me as music did.

When Bob Dylan came up in connection to the Beat generation, Edwards recounted her own experience of how after Dylan played one of his earliest gigs near Stanford University—where she was a college student at the time—she left with the impression that “the guy couldn’t sing and was going nowhere.” And when she sought to capture 1960s counterculture and rising opposition to the war in Vietnam, Edwards characterized the student protests she attended as ardent but often devolving into stoned people arguing about who left the beach towels in the car. I loved her irreverence. I also appreciated being disabused of my romanticized visions of the past, of poets, and poetry. I realize now that it allowed me to begin seeing myself as a possible poet.

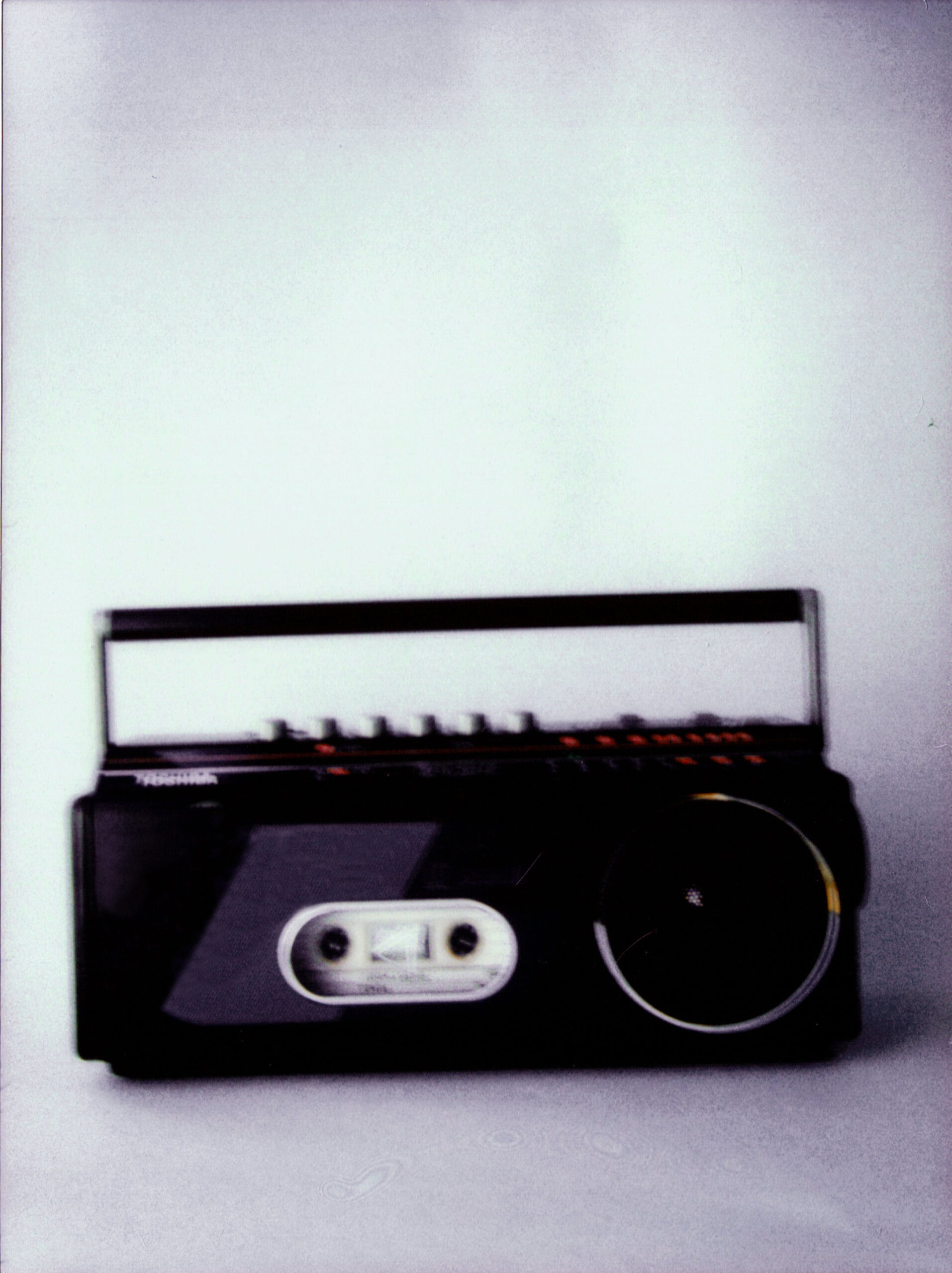

Another memorable moment along the way remains the day Professor Edwards walked into class, placed a boombox on her desk, and proceeded to play “It’s Tricky” by Run DMC:

It’s tricky to rock a rhyme

To rock a rhyme that’s right on time

It’s tricky tricky tricky

It was an arresting, incongruous image: Professor Edwards nodding her head to the beat as her students shifted in their seats, eyes wide in disbelief. The music itself—out of place on a campus steeped in Grateful Dead and Creedence Clearwater Revival—made me feel instantly connected.

While I considered “It’s Tricky” one of Run DMC’s weaker tracks—”Rockbox,” a personal anthem off their 1983 debut album, would have been my choice—I was nonetheless delighted—galvanized even—by this unexpected happening in poetry class. If Edwards meant to shock our systems a bit, she did. But what she really did was awaken her students to soundwork in all its forms while bridging the canonical divide between “high” and “popular” culture. It was a deft move, for not only did it inject levity—propelled by heavy bass—it served to highlight the prevalence of literary device in everyday life.

As the semester progressed and our scholarship deepened, I came to see that “boombox moment” as a metaphor for what 20th-century poets themselves were doing. Professor Edwards’s act of pressing “play” on Run DMC disrupted our expectations by embodying the fragmented whimsy, linguistic play, and expanded parameters that characterized poetry of the post-war era.

Edwards’s ability to illuminate the workings of a poem tempered her rigorous standards and formal comportment. It was her humor, however, that rounded out the experience, making both her and the poetry more accessible. I came to see her opening act on that first day of class as somewhat tongue in cheek—good-natured subterfuge.

All this to say, I don’t have a particular teaching strategy from Professor Edwards to pass on. I remember the semester with her impressionistically—as one sometimes does when it’s the totality of an experience that leaves its mark. The principal facet that shone brightest for me was her presence—authoritative yet generous. It’s what I sought to emulate when I later became a teacher myself. I wanted to convey a similar mix of authority and levity as a way of connecting with my students. In order to exert that kind of presence, however, I had to open up—the way Professor Edwards did. She established trust by giving us glimpses of who she was—with humor and humility. Her example proved more useful to me than any exercise or activity.

While I never walked into class wearing a cape or with a boombox in hand, I came to understand the power of disrupting students’ expectations as way to keep them interested. And, if I can find a personal correlation to what I am teaching that might speak to them, I incorporate it. If I can find a way to poke fun at myself or highlight my own fallibility, I do so. If I want to raise the bar from the start, my expectations must be conveyed as a form of respect and faith in their abilities—not as a form of control. In short, I have to give of myself to inspire their investment.

The principal facet that shone brightest for me was her presence—authoritative yet generous.

Without the tension of Professor Edwards’s perceived incongruities—that entertaining yet exacting appeal—I might never have dared to show her some of my earliest poems. Writing in solitude—practically in secret—I was hungry for feedback. Since there were never any “participation awards” on her watch, I knew she would be a discerning and forthright critic. I felt vulnerable taking the risk, but I also sensed munificence. One day after class, I handed Edwards a folder of my poetry with a plea for advice.

A week later, Professor Edwards called me up on the phone to tell me she had read my poems. Twice, in fact. The first time, after enjoying a couple of glasses of wine. The second, just before hunting down my number. Then she invited me to a dinner party at her home. I didn’t know what to make of the invitation. Did this mean she liked my poems? Or that I needed an in-person intervention to make me stop writing them?

It was a Saturday in March, still quite cold in Vermont. I remember standing on Professor Edwards’s porch, feeling intimidated, reluctant to ring the bell. I could hear laughter coming from the living room, where a gathering of her older, more seasoned graduate students was underway. I also remember being taken aback when Edwards answered the door wearing an over-sized tie-dye, her silver hair down around her shoulders. Brandishing a water gun, she smiled and promptly shot a dose of Jack Daniels into my mouth. We’re bowling for books! she announced and beckoned me in. Initially, I was stunned. But, in retrospect, the scene made perfect sense. I should have imagined that a rambunctious get-together was much more in order than a buttoned-up, tweedy event. What I didn’t expect was that Margaret would see something promising in my poems and that we would end up friends. Or that we’d be writing each other letters across three decades ever since.

Tina Cane

Tina Cane serves as the Poet Laureate of Rhode Island where she is the founder/director of Writers-in-the-Schools, RI. Cane is the author of The Fifth Thought, Dear Elena: Letters for Elena Ferrante, poems with art by Esther Solondz (Skillman Books, 2016), Once More with Feeling (Veliz Books 2017), Body of Work (Veliz Books, 2019), and Year of the Murder Hornet (Veliz Books, 2022). In 2016, Tina received the Fellowship Merit Award in Poetry from the Rhode Island State Council on the Arts. She was also a 2020 Poet Laureate Fellow with the Academy of American Poets. Her debut novel-in-verse for young adults, Alma Presses Play (Penguin/Random House) was released in September 2021. Her second novel-in-verse for young readers, Are You Nobody, Too?, is forthcoming from Make Me a World/Random House. Cane is also the creator/curator of the distance reading series, Poetry Is Bread, and the editor of Poetry Is Bread: The Anthology (forthcoming from Nirala Press, 2023).

Author Photo by Cormac Crump.