About 20 years ago, I took a two-day class with the writer Harry Mathews that promised to “eliminate the reticences writers face about their work.” Amazingly, the class did just that, curing me forever of so-called writer’s block. In the decades that followed, I’ve brought what I learned from Harry into my own creative writing classes, sharing with my students Harry’s wisdom and magic.

At the beginning of the first day, Harry asked us to close our eyes and remember what it felt like when we were first learning how to write. Harry meant this literally, directing us back to the early stages of the process, when we began to make marks on paper. What I remembered was gripping a fat pencil, writing on newsprint printed with blue lines and red dashes. I remembered frustration and clumsiness as I tried to make the correct shapes of letters. Perhaps unsurprisingly, my memories were remarkably similar to those of my classmates and to Harry’s. Harry offered the hypothesis that because our first mechanical experiences with writing were difficult, writing ever since has been at least partially associated with struggle. When I have students do this exercise, what I want them to take to heart is that however fun writing can be sometimes, it’s unreasonable to expect it to be pleasurable all the time.

Harry had only two rules in class. The first rule will be familiar to teaching artists. When given an exercise, we were to write continuously until the allotted time was up. The second rule was that when we weren’t writing, we weren’t allowed to take notes. Taking notes is another way of not paying attention, Harry said, adding that we were, however, encouraged to doodle as much as we wanted. There’s research that backs up Harry’s second rule, the idea being that if you’re taking notes, you’re always a few beats behind, whereas if you’re drawing, you’re integrating knowledge in a way that’s more closely aligned with how the brain remembers and creates.

With writing, there never is a right way to do anything, and if we want to continue to write, then the sooner we can make friends with this idea the better.

The class consisted of a series of exercises drawn from Harry’s many years working with the Oulipo—the Ouvroir de Literérature Potentielle, or, in English, the Workshop of Potential Literature—a French writers’ group of which Harry was the only American member, a fact always mentioned in his bio. The Oulipo’s most well-known member was the writer George Perec, who famously wrote a novel in which the letter “e” is never used, a seemingly impossible task, though consider the fact that someone managed to translate the novel from French into English, also avoiding the letter “e.” Many of the Oulipo constraints are almost mathematical, like “N+7,” in which the nouns of a text are replaced by the nouns found in the dictionary seven entries later. The Oulipo exercises, like the ones we did in class, are intended to make a game of writing, allowing the writer to focus on the playing of the game rather than on the “reticences” that make it hard to write.

Here’s one of the games we played: Harry passed out copies of a part of a poem written in Greek. He then asked us to translate the lines. I think the text was from the Iliad, but it doesn’t really matter, since neither I nor anyone else in the class could read Greek. My first thought was that it obviously wasn’t possible to translate the lines, my second, that it was rude and mean of Harry to ask us to do such a thing. But I knew the game was to write no matter what, and staring at the shapes of the unfamiliar letters, I started to see syllables that hinted at words. I wrote these down, feeling silly and embarrassed at the nonsense that I then had to share out loud with the class. I was surprised by what the other students in the class read. In their translations, I heard an echo of real poetry, something wild and exciting in the language, something that maybe couldn’t be reached by more conventional means.

Because I’ve taught this same exercise over the years, I’ve come to expect resistance from students, especially those, like me, who want there to be one correct answer. But with writing, there never is a right way to do anything, and if we want to continue to write, then the sooner we can make friends with this idea the better. As writers, we’re always translating things imperfectly, we’re often on the edge of embarrassment and most of the time feeling unsure of what we’re doing. This is where the tension in stories, poems, and essays comes from, the moments when the writer walks the tightrope of expectation and desire, uncertainty all around.

That’s not the whole story, editing and revision being separate and important parts of the process. But first drafts and last drafts are related to each other, sharing a DNA of language, intention, and shape. It’s on the topic of shape that Harry’s class and his writing have influenced my philosophy of writing and teaching the most.

If uncertainty is unavoidable for writers, the same thing can be said for failure. But what does failure mean? If a piece of writing doesn’t work out, that’s not failure, that’s an experiment. Real failure is not being able to write at all. For one of the exercises in Harry’s class, we wrote sestinas, my first attempt at the form. There was nothing redeeming about my efforts, but I did manage to write a complicated poem in a short amount of time because the format of the class didn’t give me the chance to second guess myself. If in your first drafts you’re willing to write a mess, to not worry about making sense, to not be afraid to write something embarrassing or dull or dumb, then it’s not all that hard to understand on a fundamental level that there’s always something there. Writer’s block doesn’t exist for me because I know that I can always write crap.

If uncertainty is unavoidable for writers, the same thing can be said for failure.

One exercise in Harry’s class involved each of us compiling a list of food words, making sure to include nouns, verbs, adverbs, and adjectives. Harry then told us to write down a sex dream. When we were done with that, we shared our lists of food words with each other, so that we each had longer lists to refer to as we replaced all the nouns, verbs, adverbs, and adjectives in our dreams. We then read these “translations” of the sex dreams out loud, and though all words having to do with sex had been removed, the results were unaccountably filthy and very funny.

Harry’s idea with this exercise is that syntax—the arrangement of words in a sentence—matters more than the words themselves. Yes, more than. This is a slippery concept and a radical one. In his book of essays The Case of the Persevering Maltese, Harry illustrates his contention by performing translations on the opening lines of Willa and Edwin Muir’s English translation of Kafka’s The Truth about Sancho Panza. First, Harry rewrites the lines so that the vocabulary is preserved, but the sentence structure is changed. The result is a stilted, unrhythmic mess. The second translation makes use of the formula N+7, which, like the food exercise and the Greek translation, produces something that shouldn’t make sense but somehow oddly does. Syntax is the arrangement of words in a sentence, and Harry’s argument is that this ordering communicates something on its own, unconnected to the words that are slotted into the form.

I’ve thought about this idea a lot over the years, but only recently has it occurred to me that what Harry calls syntax could also be referred to as voice. We recognize people we know by their patterns of speech. The same goes for writers or for characters in books, except that when we read, we also have access to thoughts, which possess their own patterns. The refining of the patterns of speech and thought is the process of revision.

As a writer and a teacher, I’m very aware that when we first write something, we are not completely sure of what we want to say or how we want to say it. The only way to figure it out—to find the syntax, the voice—is to keep experimenting, writing, and editing until the pieces settle into place. Exercises like the ones I learned from Harry invite in the unexpected, disturbing our normal patterns of syntax. A different syntax equals a different voice equals a different meaning.

Maybe it’s not surprising that when an unfamiliar syntax presents itself in early drafts, it can be easy to discount, or worse, to react to with horror. As a teacher, it’s my job to say, “Listen, there’s your voice, keep going.”

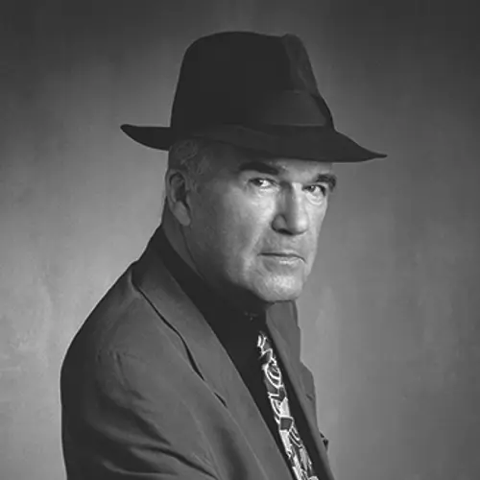

Luis Jaramillo is the author of The Doctor's Wife, winner of the Dzanc Books Short Story Contest, an Oprah Book of the Week, and one of NPR's Best Books of 2012. His novel The Witches of El Paso is forthcoming from Atria Books in the fall of 2024. He is an Assistant Professor of Writing at The New School and is the Chair of the Board of Directors of Teachers & Writers Collaborative.