It’s no secret that many college graduates lack competence as writers. Too often students enter the university with poor writing skills and leave four years later having made little or no progress at improving them. Debates about how we can best change this run the gamut. Some say we should return to the basics, especially in the first-year writing classroom. They suggest that teaching sentence structure, readability, clarity, and style, instead of rhetorical strategies, will produce better writers. Others argue that teaching the basics of sentence structure and grammar to college students is a waste of time and money. They believe that college writing courses should instead be geared toward teaching students the best strategies to write successfully in the workplace.

While these and other approaches must be considered and evaluated further, there is one important truth that we should remember when it comes to understanding why many college students struggle with the subject.

Writing is hard.

Young adult novelist, Walter Dean Myers describes it best in his craft book, Just Write: Here’s How. He says, “Writing is a sometimes joyous, sometimes difficult trek through words, sentences, pages, and chapters. It is no task for the fainthearted.”

As a college writing teacher and an aspiring novelist, I know that writing tests your grit. To be a writer requires having the willingness to take feedback that is often like a punch to the gut, and the fortitude to get up and do it all over again. It asks you to put yourself on the line, to reveal truths about yourself, to be vulnerable, only to be told that you did poorly on an assignment because your structure or message lacked clarity.

In discussions I’ve had with students, I’ve found that many struggle with writing because they misunderstand what it means to be a writer. They see writing as a natural talent—you either “got it or you don’t.” Since many assume that they “don’t got it,” they feel that they lack control in this area and are subject to the whims of fate. They say, “What’s the point in trying when the next teacher will just judge my writing based on their own set of ‘random subjective rules’?” Or they argue that the quality of writing isn’t something you can actually measure, that “It’s only a matter of personal taste.”

What these students fail to realize is that just because they have had negative experiences with writing doesn’t mean they are “bad writers,” that their writing identity has been set in stone. But before they can hope to change their writing identity, they need to be persuaded that writing is not a passive endeavor; that becoming a stronger writer is even possible.

The first step in helping students become stronger writers is getting them to change their attitudes toward and perceptions of the most dreaded and time-consuming parts of the writing process—feedback and revision. Students often find this stage of writing painful because of the red pen’s fearsome slashes. It is understandably easy for them to feel personally attacked by this initial feedback. The thoughts and ideas they struggled to put down on paper suddenly appear defenseless, bloodied, and “defeated.” The pain of writing is why many students just look at the grade on the paper without reading the feedback.

But writing is actually a very forgiving process. It offers us second, third, fourth chances to get it right. A first draft doesn’t dictate your worth as a writer. In my classes I have seen that if students can learn to accept feedback with their defenses down and embrace the art of revision, they can see how it’s possible to become better writers. By actively engaging with the process they not only strengthen their writing skills but develop a more confident writing identity as well.

In the past, I’ve had students email me, contesting a grade they received on a paper. Based on the questions they ask me about my rationale for the grade, it soon becomes clear that the students have not looked at my feedback or understood its purpose. I point them in the direction of the feedback and grading rubric, and I walk them through specific parts of the paper that could be strengthened, giving them resources, examples, and tips to help them learn and review writing principles. I ask them what their peer reviewers said and what they personally thought of that critique as well. They are often surprised when their peers have made suggestions and comments similar to mine.

I always let my students know that they do not have to accept every piece of feedback that reviewers or teachers give them, but that they must consider it carefully, and learn to use feedback to help them see where their writing needs more clarity, where it falls short of achieving its stated aims.

Once we have walked through the revision process together, I often notice that students will actively start to seek out feedback from instructors, peers, tutors, family, and friends. They are better able to understand what makes a piece of theirs succeed or fail, and to use the feedback they get to see where and how to make improvements.

When the feedback and revision stages of the writing process are taken seriously and when clear guidance is given to students about the importance of this stage, students’ perceptions of themselves as writers begin to change. They are able to see how this part of the process allows them to find their voice, refine their thinking, and clarify their thoughts and ideas. Many find this understanding extremely liberating.

As a teacher, I realize that I can only do so much when it comes to helping students transform their writing identities and become stronger writers. In my feedback to them, I point out ways they can work on the goals they have set for themselves. I offer tips, guidelines, resources, and examples, but then it is up to them to figure out their writing process, to find what works best for them. Once I give them the tools, I work with them so that they can learn to identify on their own the areas where they need improvement. This can be hard to do. It takes a great amount of effort to take control of your writing, and sadly, many students do not put in the work needed to master their struggles with writing.

But even if this is the case, I want them to understand that writers are made, not born, and that to think that no one else struggles with writing or writes multiple drafts shows a true misconception of what it means to be a writer.

We can teach the fundamentals of writing and strategies for writing in the workplace, but at the end of the day, we’ve got to acknowledge that the main reason many college students struggle to write well is because the task asks a great deal of us personally, emotionally, mentally, and physically. It asks us to do hard things, to confront our weaknesses head on and to find strategies to conquer them. To learn how to write well, students must first believe that it is possible to become better writers, and then use the tools and strategies they learn to construct their new writing identities.

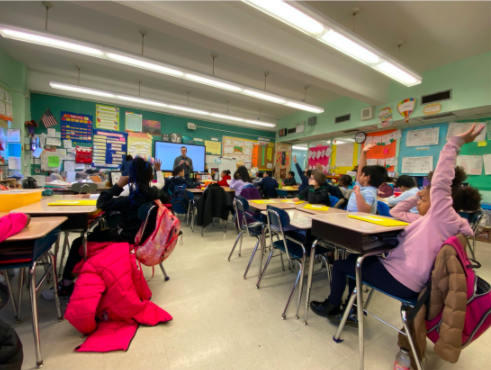

Photo (top) by imgix on Unsplash

Angela Lankford lives in Provo, Utah, where she teaches basic composition courses as an adjunct instructor for Utah Valley University by day and works as an online adjunct instructor for Brigham Young University–Idaho by night. She also works a literacy specialist for a community adult literacy program called Project Read where she teaches life and employment skills, reading comprehension, grammar, and vocabulary. She enjoys writing young adult fiction in her spare time.