Picking at the

soil

grains

of my childhood

play

a little longer

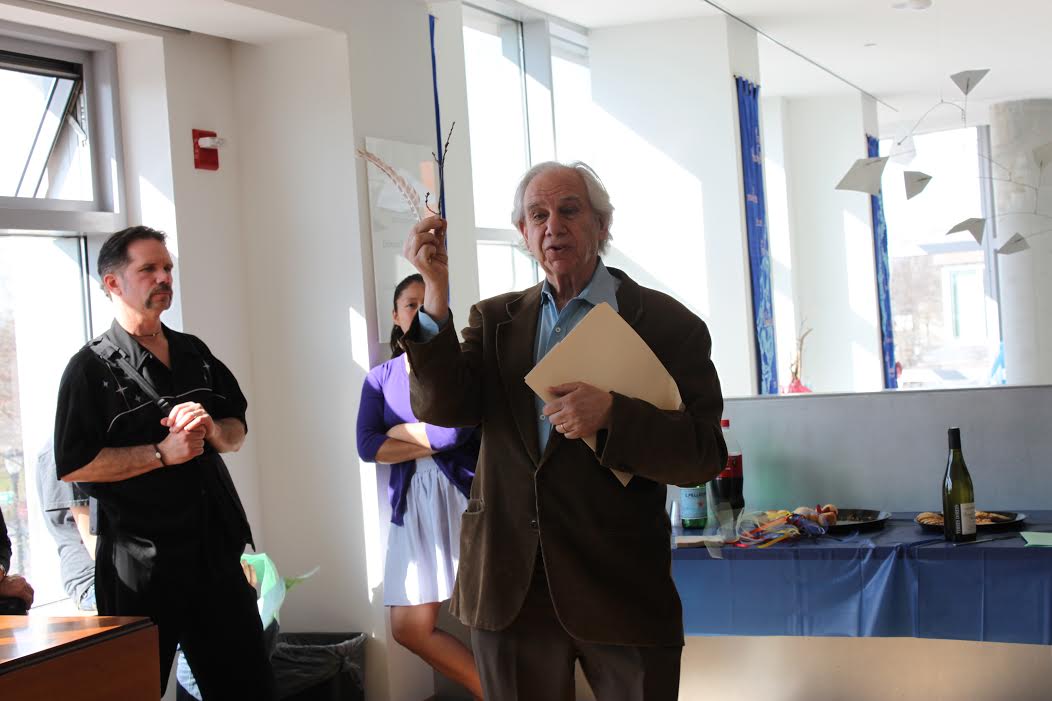

Richard Lewis, 83, left his door open for me. It is on the fourth floor of a strange old office building in Astoria, Queens that houses three funeral parlors and a museum. Short, quiet, compact, like his poetry, he offers me a seat amidst the companionable clutter of his Touchstone Center for Children, fifty years old in 2019 and still functioning as a kind of stubborn song tree beneath which children are taught poetry.

The poet, author of over thirty books for children and adults, is the grandson of European Jewish immigrants who settled in Manhattan. His mother was immersed in literature, his father painting. His father’s childhood, he recalled, was difficult. “When [my father] was twelve or thirteen, his father deserted the family. He had to go out and find a job. He roller-skated up and down Lexington Avenue delivering flowers.”

I was struck by Lewis tying together tragedy and work with an image normally associated with play. In his essays on children, play and poetry weave in and out of each other organically.

“Play,” he said, “or the language of play, deals with the intense way children have of building bridges to the unknown and the known.”

At his workshops, before getting down to writing, Lewis may comment on the blueness of the sky and have his students—their age range can vary from five to fourteen—take some of that blueness and rub it into their hands, or onto their knees. If they want, they can safeguard it there and take it out again at night for a glimpse of the blue sky beneath the black sky.

“It’s a way of going straight to the poetic, of transforming their world. They are given the freedom to use objects any way they want.

Lewis’ early life would seem to make him an unlikely apostle of play, which, in its spontaneous leaps of imagination, he regards as a form of poetry. As a boy, he was fascinated by Arnold Schoenberg’s atonal twelve-tone music, and also the poetry of Dylan Thomas and William Blake. His creative life as a young man was a balancing act between music and poetry. At Bard, he majored in music composition and studied philosophy with Heinrich Blücher, Hannah Arendt’s husband.

“On the first day of class, in his beautiful German accent and smoking a cigarette, he looked around at us with these keen eyes and asked, ‘What is life?’ And we all sat there trembling. ‘This is what we are going to be talking about’.”

Essentially, it is what Lewis talks about with children. Only instead of beginning with philosophical exploration, he begins and ends with imagination. “Give me your thought,” he said to one child. “Put it in my hand.”

His confounding simplicity, his radical questioning of conceptual reality, make him sound at times like Richard Lewis Roshi. But he claims no immersion in Zen, profound or superficial. He cherishes its poetry. He loves Bashō, and has taught Chinese Zen poetry to grade school students in Hingham, Massachusetts. Mostly, his assignments come from the New York City school system, but he’s also done workshops for Poets House in Lower Manhattan, which offers poetry programs to children as well as adults.

Lewis tells his evolutionary story slowly, as if in fact we were sitting across from each other beyond the pull of time. I discovered that he could be as comprehensive about the details of his life as he is concise and mystical in drawing me into the world of children and poetry.

I learn how he almost made music his life’s work after graduating from the Mannes School for Music. He gave thought to becoming a composer, but concluded it was financially unfeasible. One could detect a slight wistfulness in his voice.

He went into publishing and got a job with Simon & Schuster as an editorial assistant from 1962 to 1963. Leonard Bernstein was doing a book on music for children. Lewis worked with him on the book.

“I was still struggling with where I was going, with what I eventually wanted to do with my life. I knew I didn’t want to be an editor or a music critic. I felt myself being pushed towards simplicity. I was walking in Central Park one day on my lunch break and had one of those intuitive moments one comes upon sometimes without knowing where it came from or why. I thought to myself, I’ve got to start thinking about children. I wouldn’t describe it as a thunderbolt, but it was a definite yearning. Something was awakened inside me.”

Lewis recalled that his very early poetry dealt with the beginnings of things. Notions about his childhood, about the childhood of culture itself. Invisible threads that became visible at precisely the right moment. His first workshop was in back of an antique shop in Englewood, New Jersey. A small group of families with children had set up an art center for their kids, and they agreed to have Lewis teach a Saturday afternoon poetry class. He recalled his nearly calamitous first-day mishap with a rueful smile.

“The kids ranged in age from eight to eleven. I had a whole outline of what I was going to say and do and teach. I began by reading some poems, and immediately saw their eyes glaze over the way children’s eyes do when they are not interested. I got the sense they felt they were back in school. I thought to myself, No no no! This is not what I want to do! So, I said to them, ‘How did you get here today?’ That got the curtain to go up. Some said their parents drove them. Others said they walked. That was all it took. Someone relating to them directly and listening to what they had to say. After that, I’d begin each session with conversation, then weave in the poets I’d brought with me, like Emily Dickinson. Eventually, this evolved into poetry workshops, where we would talk about feelings, and they would write about them. All of that grew out of the question, How did you get here?”

A couple of the poems from those first workshops appeared in Lewis’ classic collection of children’s poetry, 1966’s Miracles, culled from the UNESCO-sponsored world-wide tour he embarked on that included India, Kenya, and Australia, as well as the US and Canada. This voyage marked the deepening, as he puts it, of “the encounter between the child that is me, and those children I am in relationship with.”

I asked him about that relationship, a relationship in which the teacher-student dichotomy seems to lose itself on the path of imagination talking to imagination. Has he remained in contact over the years with any of the children? He says, with an apologetic smile, that he hasn’t.

“The children go very quickly from one grade to the next, from one stage in their lives to the next. Children’s lives are very busy. You are always hoping that what you have taught awakens in them a life within a life, and that in some way part of it remains.”

For Lewis, children and their poetry remain part of an ever-evolving present moment. There is no nostalgia, despite his advanced age, as there is no sense of a past lost. He will sometimes awake at 4:00 in the morning, he says, with thoughts about his twin subjects, and immediately enter them into the ongoing journal he’s been keeping almost from the beginning.

It is hard to get him to talk about specific children. Perhaps he feels that by mentioning one he will be effacing so many others. But after a long, thoughtful silence, he remembers Paul, age seven at the time, who he met in San Francisco during his Miracles tour.

“I don’t recall the full context of my conversation with the children that day, but it was about the world. This particular child was hunched under a piano, writing. He didn’t say anything afterwards as I went around the room. He was shaking a bit. This is what he wrote: I love you big world. I wish I could call you and tell you a secret. I love you world. It’s a child’s love poem.”

Lewis looks up, his face full of love. The poem from the distant past alive in his face, in his voice. The boy, now a middle-aged man, becomes that boy under the piano again.

“It’s not a complex poem. It’s a gesture of embracing this thing called the world. What resonates for me is the way he and other children are equipped with this amazing quality of perceiving life in all its beautiful complexity, the good and the bad, and finding ways to make sense of it. It is genius. That desire to reach out, to connect, is one of the things children have to teach us. Children are our most profound teachers.”

In The Journey Within, a late-80s film about Lewis’ workshops at the Louis Armstrong Intermediate School in Queens, the poet raised the question, What is bigger, the world inside or the world outside? A boy replies, “The world inside, because there is no end to it.” The imaginative scope of his answer so impressed me I penned a question for Lewis in my notebook: What have been the effects of computer technology on the imagination of children?

Lewis did not answer right away. He seemed to follow the question’s path with a knotted inward gaze. His answer came with meaningful gaps between the words, as if wanting to leave space for possible revisions.

“For one thing, it has certainly affected concentration. If you are constantly looking at a cell phone, and your world is focused on that square, that box, I think you tend to forget what’s around you. Your life becomes more and more dependent on the experiences being shown in that piece of equipment. I try to free my students from the gravity of that little box by opening them up to the world around them—the sky, the clouds in the sky, the light in the room. What happens with the computer is that it’s directed at you, not with you. It’s a different kind of shaping of the imagination. You push this, and do that, and an image comes up. Of course, one can argue that the computer too was created by imagination. That is no doubt true. It is the product of one of the many levels of imaginative thought. But I sense that’s what is happening is that the machine is becoming the substitute for the interior imaginative process.”

Undaunted, he labors in his office, with the help of an intern, digitizing fifty years of film, tapes, manuscripts, odd notes. Boxes filled with stuff seem to climb out of the walls above a lonely bag of peanuts resting on his desk. After his pilgrimage of fifty years, the poet must eat. I smiled. It was a very small bag. Lewis makes me happy.

Read more about Richard Lewis’ influence on the teaching artist field here.

Image (top) via Poets House

Robert Hirschfield is a New York-based poet and nonfiction writer. Much of his nonfiction work are feature pieces on poets such as Chana Bloch, William Stafford, Tuvia Ruebner, Muriel Rukeyser, and Robert Hass. His work has appeared in Salamander, The Jewish Review of Books, Tricycle, Sojourners, and The Writer.

One response to “How Did You Get Here”

In the mid 80’s, I was an Art Teacher Intern at the Lewis Armstrong Middle School in Queens,

I was a student teacher and helped in the schools art museum. Paul Longo’s name comes to mind. I believe he is the person who put me on to your book, MIRACLES. When I left the program, I worked as an Elementary Teacher as well as an Art Teacher in several public and private schools.

Your book inspired me to teach poetry to my students. Today I am retired in a small home in Woodstock, NY.

I was unpacking and found MIRACLES to our aside for safe keeping. It reminds me of some

special moments working with children. I now have three school aged grandchildren who will enjoy reading your precious collection of poetry! (If I can steal them away from their laptops! )