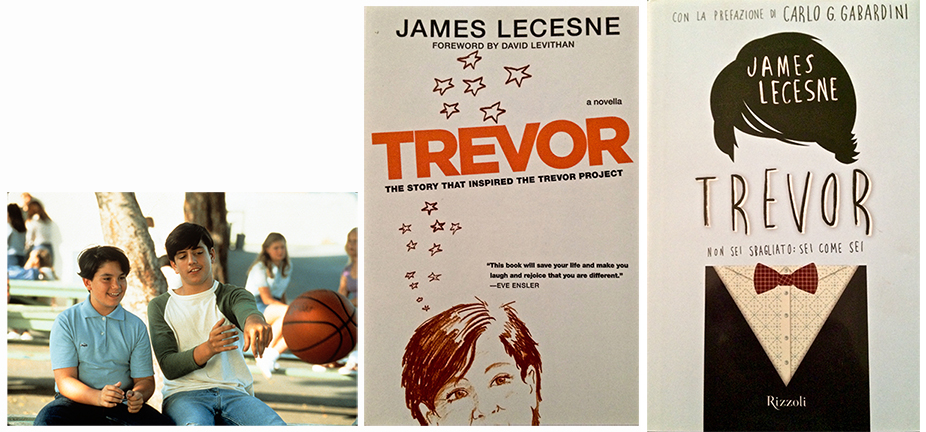

James Lecesne has been ranked “among the greatest storytellers of his generation” by the New York Times in a review of his most recent Off Broadway solo show, The Absolute Brightness of Leonard Pelkey. He wrote the short film TREVOR, which won the 1995 Academy Award for Best Live Action Short and inspired the founding of The Trevor Project, the only nationwide 24-hour suicide prevention and crisis intervention lifeline for LGBT and Questioning youth. He created THE ROAD HOME: Stories of Children of War, a play which was presented at the International Peace Initiative at The Hague. For TV he adapted Armistead Maupin’s Further Tales of The City (Emmy nomination) and was a writer on the series Will & Grace. Lecesne has written three novels for young adults and created The Letter Q, a collection of letters by Queer writers written to their younger selves. He is the executive producer of After the Storm, a documentary film that tells the story of twelve young people living in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. Lecesne teaches story and structure at New York Film Academy and he leads intensive workshops called The Story Net.

Matthew Burgess interviewed James Lecesne on August 31, 2015, at Matthew’s apartment in Brooklyn, New York.

Matthew Burgess: You’ve taught in a variety of settings to students of various ages, and your subject is usually “storytelling.” What attracts you to this term?

James Lecesne: Everybody knows how to tell a story. One of the first things that you begin to do, as a human being, is to try to tell a story. There are studies that show that you start telling stories before your second year of life. You attempt to construct the basic working models of story. It’s in our DNA.

MB: So, in your classes and workshops, you give people tools for telling their own stories?

JL: I think that every story that a person tells is basically their own story. Whether you tell a story that’s strictly autobiographical or whether you tell a story that’s fictional, you are telling some aspect of your story, which is based on what you believe.

Basically, you’re creating this little spaceship and the better the structure, the further it can travel out and withstand the pressures of time and space. It’s an amazing thing to watch a story travel. You never know how far it’s going to go.

A story is like the intergalactic spaceship that you construct that will travel out through time and space. What’s inside of it is what you believe. That’s why you’re making a story-because you believe something to be true, and you want to either warn people or pass on valuable information and wisdom. Basically, you’re creating this little spaceship and the better the structure, the further it can travel out and withstand the pressures of time and space. It’s an amazing thing to watch a story travel. You never know how far it’s going to go. You may feel like, “Oh my God, I hope it gets beyond next week.” Then it goes out maybe years and keeps doing its business. That’s amazing. The reason that I teach story and structure is to help people construct a better vessel that can hold what it is that they believe.

MB: I’m not sure if my students have arrived at what they believe. Many don’t have that kind of certainty yet.

JL: But that’s why people write. We write to find out what it is we believe, which is often surprising and confounding and enlightening. Some people may start with a belief, but I think the best writing and the best storytelling is a process in which we surprise ourselves and learn something from our own story, something we didn’t know prior to writing.

MB: Doesn’t the process of writing often involve changing or revising your beliefs?

JL: It’s the experience of encountering yourself. Your true self. Your authentic self. As opposed to changing your mind. It’s about, “Oh, that’s who I really am.” Of course, it’s a process of recognition. That’s the excitement of it. It’s not brand new information. It’s information that’s deeply embedded and encoded within your being that comes to the surface.

MB: I’m curious about the connection between storytelling and your Buddhist meditation practice. It is my understanding that, in meditation, one comes to observe the “stories” that our minds construct about who we are. On some level, isn’t the goal to recognize these narratives as fictions?

JL: Exactly! But as a teacher, my job is to help others recognize that their “fictions” are expressions of who they are on the deepest level. I once had a student in a week-long story workshop with about ten students in the group. Every time there would be a new person to workshop their story, she’d say, “You know, I’m not ready,” so we’d move on to the next person. Finally, I asked, “Why aren’t you ready?” She replied, “I just can’t decide between these two stories. I’m trying to decide which story to do.” On the last day, I said to her, “Why don’t you just tell us very briefly both stories?” She told us that one story was autobiographical and the other one was a fictional story. Without getting into the details, ten people sat in the room and looked at her and responded the same way. “They’re the same story.” “No, they’re not,” she said. “One is made up and one is my life. The story of my life as a twelve-year-old, and the other one is about a boy who’s thirteen and lives in a kingdom.” But they both involved the same issues that she was dealing with and she could not see it. She kept insisting that they’re totally different. It took us about a good half hour to convince her, to show her that they were exactly the same. She just couldn’t see, because she was so invested in the idea that the made-up story was not her and so invested in the idea that the autobiographical story was so revealing. She couldn’t understand that, in fact, they were both equally revealing and equally concealing.

MB: Did you lead her in the direction of the autobiographical telling or the fictionalized version?

JL: What I do is to connect people to what is underneath; the rest is up to them. The belief that you’re trying to communicate is what I’m interested in, what is enlivening or animating the story. Whether you choose autobiography or fiction or science fiction, it doesn’t matter. It’s coming from the same deep center, which springs from what you have experienced in your life. Out of those experiences come the beliefs and out of those beliefs come the premise for your story. That’s all you got. Where else would you go? The Akashic records?

MB: Do you find the classroom to be an effective laboratory for story-making?

JL: It works with a strong teacher to guide it. I find that individual feedback is not so helpful, because people are always trying to find solutions to other people’s stories. Like, “I know what should happen. He should kill her.” “I know what should happen. They should have sex.” People often want to move directly to the solution as opposed to being able to hang out in the mystery.

MB: Who are your great storytellers?

JL: Charles Dickens is one. When I was about nineteen, I read through all of Charles Dickens’ works. It was an education in terms of character and story and structure. He’s just unbelievably brilliant.

MB: What about children’s books?

JL: When I was really young, I was crazy about the series of books called The Borrowers. I recently had a conversation with our friend, Brian Selznick, about this because he was obsessed with them too. The Borrowers were very tiny people who lived in the floorboards of a house of bigger people. They lived this sort of secret life as little tiny people living off the droppings and scattered things. The big people would lose a spool of thread, and they would take it in and use it as a table.

Now I’m convinced that I needed this story to get me through that period of my life, that period when I was feeling-these people I’m living with are not my people. I had to live a secret life at eight or nine years old. I didn’t have a name for it, but suddenly there was The Borrowers, and I became obsessed with them.

I was talking to Brian about this and we were talking about how the story of The Borrowers was a metaphor for the secret life of us, secret gay kids. Growing up with another identity underneath the main family identity. Now I’m convinced that I needed this story to get me through that period of my life, that period when I was feeling-these people I’m living with are not my people. I had to live a secret life at eight or nine years old. I didn’t have a name for it, but suddenly there was The Borrowers, and I became obsessed with them.

MB: Were you also telling stories at this early age?

JL: I was part of a group of kids on my childhood block. We were pretty busy with stories like radio programs and films. We had circuses, fun houses, shows, plays. We were very, very busy queens. Actually, I think I was the only queen. I was very into it. It was essential to my early story-making life.

MB: Were you the ringleader?

JL: Walter Stevens was the ringleader. He always had a great idea. He always masterminded something. I’m so grateful that he was there in my life early on, because he really got things going.

MB: And all of this was happening in the neighborhood-on the block?

JL: Yes. It was a little dead-end street in suburban New Jersey. There were maybe twelve or fourteen houses all exactly alike, and we played together every day.

MB: What did you use as a stage or a playhouse?

JL: Backyards, garages, clubhouses. We once made a film with a Super 8 camera. We must have been in between sixth and seventh grade, and we decided to make a horror film with a reel-to-reel tape recorder for sound. We had to sync it up ourselves. Can you imagine? Every day, we would go into somebody’s house, because our parents were at work. We’d go into the living room and we’d make a scene from the film, and then we’d get in trouble so we’d have to move to somebody else’s house. The film took place in the same living room, but the décor was completely different from shot to shot, because we kept getting in trouble and having to move to someone else’s living room down the block.

MB: Do you remember when you first thought you might become a writer?

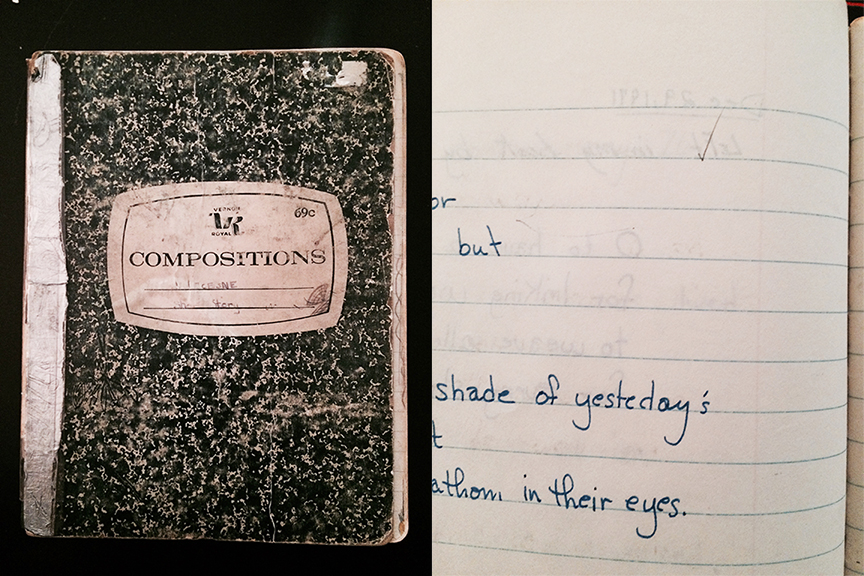

JL: Yes. In my junior year of high school I had a teacher named Mr. Shust. He was really strict. He made us keep a journal. There were two things that happened. The first was that I began to write in the journal and it was just like, “Okay, here we go.” He would collect the journals-I think once a month-and read them. He would just make a check on things that he thought were good. He didn’t write in the book, but just knowing that he was reading it was enough of a relationship. It developed in me very early a kind of relationship between the interior and the exterior. Me and my audience. It wasn’t like I was writing for him, but I was aware that he was going to read it.

The other was that I read an E.E. Cummings poem aloud in the class and he was amazed that I understood the poem and had a grasp on its meaning. He was rarely amazed. He was very bored with us-if you could amaze him, that was really something. It was the only time I did, but it made me understand that I had an “in” to language.

MB: Do you remember the poem?

JL: “In Just Spring.”

MB: That’s incredible. I just finished writing a lesson plan based on teaching “In Just-“ with my second-grade poets.

JL: He also introduced us all to a book of short stories called Point of View. It has John Cheever and Dorothy Parker and Eudora Welty and Katherine Mansfield. We read them all, and that was my adult introduction to the world of story. They were all so brilliant and they all had something to say. Each one of them had a very strong point of view, but they also had an incredible voice. It’s not just about the belief-it’s also about the voice that can back it up. That was the year I discovered the theater and I wrote my first play.

MB: What was it called? Do you remember?

JL: It was called Never More the Wind. I had come back from my first experience in theater, in summer stock as an apprentice. I came back to my all-boys high school and said, “We have to have a theater. We have to have a theater department.” I got a teacher and got some students together and I was like, “Let’s put on a play and I’ll write it.” It was just really terrible. I don’t think we ever actually did the play, because it was so bad, but then eventually, we did stage a play.

What literature and what the worlds of language and the theater gave me was the opportunity to be genderless and to be all-sex. Not sexless, but to be anybody. I could read Jane Eyre and I could be Jane Eyre.

MB: So you became Walter Stevens at that point? You just gathered people together and said, “Let’s make this happen”?

JL: Yeah, although I didn’t think of myself as that. Once the theater came into the picture, that became my thing. That was going to be my means of expression one way or another. One of the things that was so important to me at that period of my life-as a junior in high school-was that I was just beginning to understand the seismic difference between me and all these other boys I was with. Because I grew up during a time in which nobody was talking about “being gay.” It was unspoken, but I knew it. And so did everybody else. What literature and what the worlds of language and the theater gave me was the opportunity to be genderless and to be all-sex. Not sexless, but to be anybody. I could read Jane Eyre and I could be Jane Eyre. I could be her. I could then inhabit the world’s literature in a very real way. In that sense, reading really saved me. It gave me the ability to create a kind of imaginative, interior life that was rich and vital, especially at a time when my exterior life was not that vital and not that satisfying. At a time when kids were exploring, I was building an interior world.

MB: Writing in the journal must have helped this process. It’s interesting that Mr. Shust’s reading of the journals made such a difference for you. Just the check mark was enough to say, “I’m reading this. I’m following.”

JL: He checked the passages that he liked. You never knew why. It wasn’t like he was correcting. Looking back on it now, I think he was responding to your voice. It wasn’t about grammar. He was able to like say, “I hear you. I hear this one.” I think it’s because he saw me. He had an ability to see everybody, and I allowed him to see into me by writing more. By trying to write as honestly as I could. That was his thing- just write honestly. He didn’t teach us grammar and stuff like that.

MB: Could you write about being gay?

JL: No. Not back then, but I could encode it. Which is, of course, what we do all the time anyway. Now we have a lot more acceptance towards the gay community which makes it a lot easier to write about. The fact that there are gay dating sites and gay marriage is legalized makes it much more understood subject too so the audience can connect with it.

MB: Do you still have that notebook? With his checks in it?

JL: Yeah. I have all of them.

MB: In your current project, The Absolute Brightness of Leonard Pelkey, you play nine different people. Do you see these characters as aspects of yourself or are they somehow distinct?

JL: As an actor, you only have yourself. It’s the same thing as we were talking about for writers. All you have is your own self, your own body, your own experience, and you make it do things. What makes it come to life is that there is some aspect of you in the character that you’re playing. I would say that these are probably nine fractured versions of me, but one hopes that each one of them is as alive and fully animated as I am myself. In that sense, I think of these characters almost independently of me. I don’t think of them as parts of myself. I think of them as real people who I happen to know. I have the good fortune to play them on stage, but I also feel like they’re actually real people with real lives.

MB: How did you learn to do this kind of performance?

JL: When I was nineteen years old, somebody gave me a recording of Ruth Draper. She was popular in the 30s and 40s, and she was huge. She toured the world and played Carnegie Hall. She portrayed hundreds of women as a solo performer. Somebody gave me that record and it completely changed my life.

MB: So Charles Dickens and Ruth Draper?

JL: Yes, and Lily Tomlin, who did a show called Appearing Nightly when I was nineteen. It was the convergence of those three things that made me think, “This is what I’m doing and I’m going to do it for the rest of my life. I don’t know how but I’m going to do it.” I was obsessed.

MB: So is this your favorite mode of expression?

JL: It’s my favorite mode. Because it uses all the skills I’ve learned-writing, acting, story, directing, producing. They are put to the best use through this form. So in terms of teaching, who knows what is going to set somebody off on their original path. I think the best thing that any teacher can do is to make as much available as possible to their students. You just lay it all out there and try to get them excited about all modes of storytelling. Or at least that’s what I try to do.

MB: Do you have a favorite lesson that you do with a group of students? A favorite activity that readers might be able to try with their students?

JL: I always start with people writing down five things that they absolutely believe to be true about themselves. “This is who I am, it’s non-negotiable.” Then I ask them to write five things that they absolutely believe to be true about the world. After students write these down, then I ask them to tell the story about how those beliefs came to be.

MB: Can you share a personal example?

JL: Something I know about myself is I’m an advocate for the underdog. Like, if I see somebody who’s struggling, I’m on it. I have to help them up the stairs with their things or I have to write about the injustice.

This nexus between personal experience and belief is where the best stories are. If you can locate that on a person’s personal map and get them to see it, they are on their way. Whether it’s fictional or autobiographical, that’s where the juice is.

MB: With the underdog example, what would you offer as the story of how it began?

JL: I was the underdog! I could probably point to twenty examples of when I was a kid of being the underdog and being the “under-gay” and no one coming to my rescue and how painful that was. I could write twenty stories right there, either fictional or, as in the case of TREVOR, which is fictionalized. Or really fictionalized, which would be the Leonard Pelkey story. This nexus between personal experience and belief is where the best stories are. If you can locate that on a person’s personal map and get them to see it, they are on their way. Whether it’s fictional or autobiographical, that’s where the juice is. That’s where the really good stuff is.

MB: What is one of the things that is on your “what-I-believe-about-the-world” list?

JL: One of the things that I absolutely believe about the world-which is basically the premise of The Absolute Brightness of Leonard Pelkey-is that from great evil comes great good. I absolutely believe that. I would go to the mat defending that belief. But I didn’t know that that’s what I really believed when I started telling that particular story. I just had an idea of a story that I wanted to tell a story about a kid who disappears from a New Jersey town. What I began to understand as I was writing the story was that the terrible tragedy of Leonard’s disappearance allows the people of the town to discover who this boy was and, more importantly, who they are to themselves. They didn’t understand Leonard’s goodness until evil took over. Out of that evil, they all found their own brightness. Not only did they find him, but they found their own voice.

We all know how hard it is to get anything into the world. Any story, any book-it takes a lot. If it’s just an idea you have in your head, that will get you to the corner; but you want to be able to go years sometimes fighting for a project or trying to finish it and get it out into the world. That requires something that’s really deep inside you, that you’re going to fight for it.

I just find this is a really good exercise for people because it gets them in touch with what it is they believe, which is where, for me, the energy is. We all know how hard it is to get anything into the world. Any story, any book-it takes a lot. If it’s just an idea you have in your head, that will get you to the corner; but you want to be able to go years sometimes fighting for a project or trying to finish it and get it out into the world. That requires something that’s really deep inside you, that you’re going to fight for it.

MB: TREVOR is one of those stories that continues to move through the world years after it was written. How did it begin?

JL: TREVOR was part of a solo show called Word of Mouth that I wrote in 1990. At that time, I heard a story on NPR about teen suicide. They casually mentioned the fact that a third of the suicides were attributable to homosexuality. I just thought it was insane. Plus, at that time, I was living through a plague. So many people of my generation were dying. In the midst of this, there was a younger generation of people that were killing themselves. It felt like a massive kill-off of two different generations of gay people. So I went back to my journals-those very journals we discussed. I also interviewed a bunch of people and that’s what TREVOR came out of.

To me, it was the actual proof of how powerful a story can be in the world. What it can do. It can save lives.

The incredible thing to me is that when I performed Word of Mouth-it was just me performing in a little theater downtown in Manhattan-I never imagined in my wildest dreams that anything would happen with it. I couldn’t have, because I used all the actual names of my grammar school and high school people and never imagined that years later they would contact me and be like, “Oh my God, I’m so sorry.” I had no idea that this little story would later inspire the founding of The Trevor Project, the only national suicide prevention and crisis intervention lifeline for LGBT and Questioning kids. To me, it was the actual proof of how powerful a story can be in the world. What it can do. It can save lives. Not only can it move through time and space and do things without you-it’s not like a puppet, you don’t have to have your hand up underneath. It’s out there doing its thing without you present.

MB: So TREVOR evolved from your high school journals, turned into a theater piece, and then evolved into a screenplay of a short film that won an Academy Award…

JL: Yes. After performing it in Word of Mouth, [producers] Peggy Rajski and Randy Stone came to me. They asked me to adapt it as a screenplay and I audaciously agreed. Then it was made into a film that Peggy directed and Randy and Peggy produced. It won the Academy Award in 1995, incredibly, and two years later, HBO offered to put it on TV. We thought it would be a good idea to put a telephone number at the end of the film in case there were kids out there in America who recognized themselves in the character of Trevor. We got Ellen DeGeneres to do a wrap-around presentation for it, so it got a lot of play. That first night it aired on TV on HBO, we received over 1,500 telephone calls from around the country-that first night! Unbelievable. In August, this month, The Trevor Project is seventeen years old. These days, we get over 44,000 phone calls a year, but we also have TrevorSpace which is like a Facebook for LGBT kids and TrevorChat and TrevorText.

MB: Meanwhile, you’ve written and published another novella version of TREVOR.

JL: Yeah. I updated the story to include text messages and social media. That book came out in the United States, and four years later, it got translated into Italian. Somehow, over there it’s news and it’s needed. I’m constantly amazed by the staying power of that particular story. Such a tiny little story.

MB: What do you think teachers can do to help prevent teen suicide?

JL: Recently, I have been reading this book titled One Teacher in 10 about the challenges of gay teachers all over the world. One of the things that comes through so clearly is that the more authentic the teacher is, the more a teacher brings themselves to the room, their full self, the more emboldened the kids are to be themselves. Every good thing comes out of being your authentic self, and I think bad things happen for a kid when they’re not allowed to be their authentic self. There is no way you can keep that authentic self down. It’s going to find a way.

Research shows that a kid is eight times less likely to attempt suicide with just one sympathetic person in his or her life. Any teacher can be that person. That’s an awesome responsibility, and it’s an even more awesome opportunity to know that you could be that person if you want to be, but you have to want to be.

In answer to your question, I think it is important to make it really clear that as a teacher, you are a safe space. If you see some kids struggling, to say, “You know what? You can come and talk to me any time. If you’re having a hard time or if you’re trying to figure something out, you can come see me after school.” It’s not like teachers don’t see kids struggling. Research shows that a kid is eight times less likely to attempt suicide with just one sympathetic person in his or her life. Any teacher can be that person. That’s an awesome responsibility, and it’s an even more awesome opportunity to know that you could be that person if you want to be, but you have to want to be. That doesn’t mean you have to save everybody’s life. It just means you have to be the one person who sees that kid and says, “Talk to me.” Sometimes it’s the difference between life and death.

The next thing is to open students up into a world that is out there. I think there’s a way to be able to direct kids toward solutions without you being the solution. You don’t have to come up with the answer. You don’t have to figure it out, but you can make available to them literature that is amazing. What TREVOR taught me was that that story which was so deeply personal is not my story alone. It is everyone’s story. Not just a gay kid’s story. It’s every adolescent’s story. It belongs not just to me, it belongs to everyone.

MB: Yes. Reading and writing can lead to a recognition of our interconnectedness. The revelation is that you are not alone.

JL: What’s so interesting is that that is the TREVOR motto: You are not alone. It is also true of literature. I think one of the things that literature does is that it teaches us how to be human. In a sense every adolescent is an underdog struggling to come up in the world and become fully human. What was so pivotal for me about reading Dickens at that point in my life was that I didn’t know how to be a human being, and I certainly didn’t know how to be out in the world. Reading can gives us the tools and the stories about how to be a human being and about what’s valuable. What do you value?

Matthew Burgess is an Associate Professor at Brooklyn College. He is the author of eight children's books, most recently The Red Tin Box (Chronicle) and Sylvester’s Letter (ELB). Matthew has edited an anthology of visual art and writing titled Dream Closet: Meditations on Childhood Space (Secretary Press), as well as a collection of essays titled Spellbound: The Art of Teaching Poetry (T&W). More books are forthcoming, including: As Edward Imagined: A Story of Edward Gorey (Knopf, 2024), Words With Wings & Magic Things (Tundra, 2025), and Fireworks (Harper Collins, 2024). A poet-in-residence in New York City public schools since 2001, Matthew serves as a contributing editor of Teachers & Writers Magazine.