Ryan Skrabalak remembers late poet, writer, and artist Bernadette Mayer and reflects on her influence in his writing and life. Learn more about Bernadette Mayer and her work at www.bernadettemayer.com.

1.

I moved to New York City in 2009 at 20 years old and enrolled in three classes at Brooklyn College. I loved Allen Ginsberg’s poetry, which more or less guided me to Midwood, where I knew he had taught in the 80s and 90s. There was even a poem of his left preserved on a strip of chalkboard on the third floor of Boylan Hall, in the classroom where Carey Harrison taught. I lived with my best friend from high school in a two bedroom apartment just off of Flatbush Avenue, across from Lenny and John’s Pizzeria, for $900 a month. I took the B41 bus to school and ate red velvet cake from Lord’s Bakery. As a boy from upstate New York, I felt supremely out of place on a 2009 local 2 train in a holey Grateful Dead parking lot tee, loss-fitting pants, and muddy, peeling boots (times change, I suppose). I so desperately wished to shed my clunky yokel-ness for a new, reinvented urban slickness. My friend Jenny said, bluntly and suggestively, “you need a pair of black skinny jeans.” In that year I remember reading Mayer’s Sonnets for the first time. “What could it be? / Friends? Purpose in life? To live / And breathe, I don’t know.”

2.

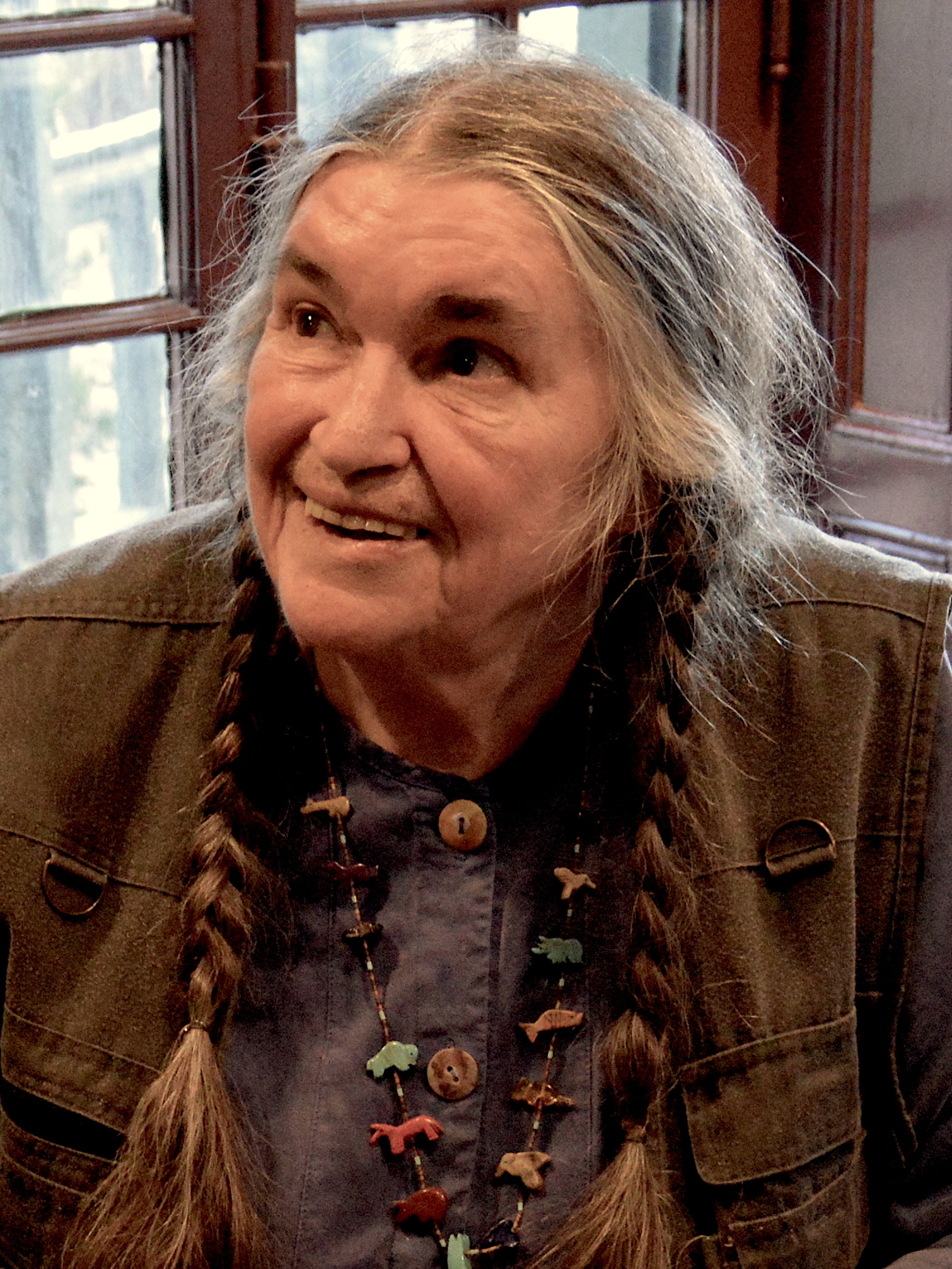

Later that same year, back home in Albany, it dawned on me that I had seen Bernadette Mayer read at a number of local venues—Valentine’s, the Albany Social Justice Center on Central Avenue, Albany Center Galleries, the Upstate Artists Guild, etc. I recalled her as the woman with the vest and the braids who had a marvelous laugh, huh. And Phil, partner and poet Phil Good, with his omnipresent blue Buffalo check plaid. I had been, up until then, completely unaware, led astray by my need to ditch my odd “rural” skin. She was, and remained, deeply local, ever-collaboratory, wearing different states of consciousness and time as if they were work clothes, and in many ways they were.

She was, and remained, deeply local, ever-collaboratory, wearing different states of consciousness and time as if they were work clothes, and in many ways they were.

3.

Bernadette gave me permission—not literally, as much as that would be in pocket to grant verbally—rather, permission via poetic osmosis. Permission to write “actual” poems, actual inscriptions of living, proof of living, proof of loving out in our social formations. Around the time I learned of her proximity to the social and cultural topography of my childhood—in high school we’d go swimming out in Nassau on summer days and drink beer under the bridge on Route 20—I subsequently learned of her “porch school,” poetry workshops for $75, lunch often included, or bring a 12 pack of Sierra Nevada Pale Ale. I was too taken with my own early-20s projections of Bernadette’s fame and my amateurish poetic self to join in. And I was even perhaps too broke for $75, or didn’t realize the value of this meeting, or all three at once.

Bernadette gave me permission to write about cake, to develop a deluxe attitude to perspective, to make sure there is laughter threading the lines at times, the wonders and sublime textures of dailiness, honing a mechanics of instinct in language, an instinct in the punctuations of experience, the practice of writing poems is the poem. Walking around the campus of The University of Tulsa last month, the poet Lewis Freedman asked me: “Who showed you how poets live when you were of the age to conceptualize a poet’s life?” Well.

—Bernadette Mayer

4.

“Forget about value as its perceived . . . and hurry to change the world in small performance as others like John Cage have done, since you can’t stop f***ing writing anyway,” writes Bernadette in a short essay entitled “Mimeo Argument” as a rebuttal to Eileen Myles’ “Mimeo Opus,” published in the April 1982 edition of the Poetry Project Newsletter. When I hold a book of poetry, I often think of this text, which I first saw on a faded PDF scan from Paul Soulellis. It is essentially the reason I began to print books, with this specific ethos in mind.

5.

“Reason studs desire with the thought of what they call complications, I heard that often enough . . . I’m going to eat a potato and read Pride & Prejudice,” letter to Bill Berkson dated June 29, 1985, from What’s Your Idea of a Good Time? (Tuumba, 2006). I heard that often enough, too. Maybe meaning: you can dream for the people you love, and you should, be magnanimous always, or: “we kiss, we plan a trip / When we awaken the night has gotten longer for our free pleasure / & though we stayed up so late examining every known desire / We still got plenty of rest.”

I find it is impossible to not begin to obsess with perspective, with encounter, and with learning when reading her work.

6.

I’ve taught Bernadette’s work to burgeoning poets, to practiced poets, and to first-year composition students alike. On my syllabus for both, for all: “The moon is coming up / I have something to do with that” (from Midwinter Day). Of systems. I find it is impossible to not begin to obsess with perspective, with encounter, and with learning when reading her work. Invariably, the questions that circulate the learning space are as dense as Bernadette’s material of which the questions are borne: “How do we know what poetry is?” “How do we remember things?” “Does the memory or the action come first?” “How much can language hold?” When I hit a pedagogical roadblock, I scan and rescan her list of journal ideas, with some favorites from students:

- Journals of: dreams, dangers, skies, answering machine messages, rooms, mail, food.

- “Write a soothing novel in twelve short paragraphs.”

- “Attempt to become in a state where the mind is flooded with ideas; attempt to keep as many thoughts in mind simultaneously as possible. Then write without looking at the page, typescript or computer screen (This is “called” invisible writing).”

- “Find the poems you think are the worst poems ever written, either by your own self or other poets. Study them, then write a bad poem.”

- “Structure a poem or prose writing according to city streets, miles, walks, drives. For example: Take a fourteen-block walk, writing one line per block to create a sonnet; choose a city street familiar to you, walk it, make notes and use them to create a work; take a long walk with a group of writers, observe, make notes and create works, then compare them; take a long walk or drive—write one line or sentence per mile. Variations on this.”

7.

I think of the inescapable generosity of Bernadette’s thinking, poetics, way of living, “an act of utter tell beyond the call . . . the endlessly inclusive Bernadette,” as described by Clark Coolidge on his back cover blurb of The Desires Of Mothers To Please Others In Letters (Hard Press, 1994). The way the words and the nodes between the words reel a reader into warmth, but not without some arcane invitation first, a letter from an admirer you know, but not in this realm, and not on this plane, but simultaneously next door, someone making a grilled cheese with sliced apples inside. To have her missing on Earth is like removing a color from the 120 count box.

To have her missing on Earth is like removing a color from the 120 count box.

8.

I’m unsure of the date, but Bernadette read poetry one evening with a smattering of other local incredible poets from Albany: Douglas Rothschild, JP García, Michael Peters, James Belflower, and others. Or some collection of them. I don’t remember where, either, which would help cement this memory in a way that would actually make it fall apart for me, so to speak. Bernadette read a sonnet about maple syrup from Scarlet Tanager, and upon finishing it, more less roared with laughter.

9.

I found a gentle didacticism in Bernadette’s work that felt like a color to use. Or a temperature to comfort the world. Her directives felt necessary: be anti-war, invert your private properties, give everybody everything, invite your friends to dinner and kiss them, eat radishes with butter when they are in season, don’t pay rent, it’s your job to mangle the language for everyone if you can, and you should. These teachings were, and continue to be, alluring in their suggestions. They orbit my thinking incessantly.

10.

In that way, and in finishing the above story with the maple syrup sonnet, after she finished the poem and laughed, she said, “Gosh I love that one so much, I think I will read it again.” And then did that. I like to think she was stepping into the work and moving around in it, feeling the haptic contours of the plethora of experience, living in its brief taut electricity. Magic on earth exists in this way, and expressed like that. Maybe magic as a concept is subjective, but I felt something beyond the terrestrial. I said hello to her and Phil on the way out, they both beamed. She had a fancy half-eaten chocolate bar in one vest pocket and an open can of beer in the other.

11.

“I think of writing as an athletic, physical activity that has to do with bodily states, being high, getting high, going on, being fast, being quick, knowing everything & being a philosopher which is of course a complete physical state of being—hands, torso, head on top of body sort of lilting and nearly falling off, moths flying at head, eyes peering into mirror, feet cross tailor-fashion, ass levitating off of uncomfortable chair, light in eyes, window if it’s night only showing self up. What an odd question,” letter to Bill Berkson dated July 4, 1981, from What’s Your Idea of a Good Time? (Tuumba, 2006).

12.

We can hope that the famous cucumbers are ever arriving, so crisp, laid perfectly glossy and pristine. Eat, eat, eat with friends, as much as possible, to enrich and deepen the feast, strata of friendship, memory, language, in the accretive way that characterized Bernadette’s approach to nearly all things, that the aforementioned things are not separate at all. We loved her so much; I hope she knew that, I think she did.

“in this really huge world in / which I woke up this morning / Thank you very much.”

That she is alive in memory experiencing us, in us experiencing each other, in continuously experiencing our memories.

Featured photo of Bernadette Mayer is courtesy of Kelly Writers House/Wikipedia Commons.

Ryan Skrabalak

Ryan Skrabalak is a poet, educator, and organizer from so-called upstate "New York," currently living in "Kansas" with his dog, Donkey. His recent work has appeared or is forthcoming in Trilobite, Denver Quarterly, NEW: The Journal of American Poetry, baest, Works & Days, and queer.archive.work, among others. He is the author of several chapbooks, including the forthcoming ASSEMBLED CLIMATE (NEW Books) and The Technicolor Sycamore 10,000 Afternoon Family Earth Band Revue (Ursus Americanus Press). He runs and edits the poetry micropress Spiral Editions in Lawrence, Kansas, where he is also an instructor at the University of Kansas and a member of AFT 6403.