By Marissa E. King and Karen Sheriff LeVan

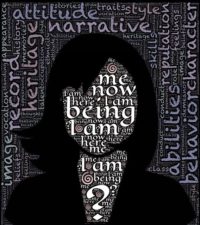

I am what I am. I am the sun after a storm, fireworks at night, and finding a shooting star. But when you see me in English, I am the bottom of the lake, in the closet, and under the bed. Like a prism, I am multi-sided.

—Machi, college student

In our work with first-year college students, we’re struck when otherwise confident students wince when it comes time to write. Even those bursting with personality among friends or brimming with confidence on the athletic field can shrink when we ask them about their previous writing experiences. Like many teachers, we’ve searched for ways to make writing practice a more inviting and positive experience for students.

In new environments, especially ones that involve evaluation, self-identity can suffer. The student writer Machi, quoted above, contrasts her self-identity—fireworks! shooting stars!—with the dreary images of how she thinks others see her. Kortney, a cheerful freshman and tenacious volleyball player, describes her own contradiction: “I may have swung hard on the court, but I tiptoed in class.”

Writing-inspired angst is a clear block to the imaginative sparkle we look for on the page. In order to move forward, it’s worth taking a moment to examine writing-identity formation.

Several years ago, we started asking students transitioning to college to describe their relationship to writing. The stories were as diverse as the students who plunked into seats on our two-year college campus, but we found ourselves lingering on the descriptions of being unseen, dismembered from their own writing voice, or, as one student put it, “like an eight-year-old lost at Walmart.” A new mother in class likened writing experiences to being wheeled down the hall in labor: breathlessly grasping her own mother’s hand for comfort and bracing for inevitable pain. Still another student remembered feeling like “a faint noise in the background” of her writing classroom.

As teachers, we can’t sweep away the pain associated with past writing experiences. But we can give students more opportunities to write about themselves on their own terms.

Our first days of class often focus on identity exploration. The goal is to harness student voice and imagination to show glimmers of multi-faceted self-identity. With a little guidance, a tiptoeing writer can uncover a helluva swing.

We like to start courses with an adaptation of the “I am what I am” lesson described in Tom Romano’s Crafting Authentic Voice (2004). Students start with “I am what I am” and then repeat the “I am . . .” sentence structure in a series of self-descriptions that draw on multiple aspects of their identity.

Unlike Romano’s longer, multi-paragraph approach, we use just one simple paragraph with a focus on writing identity as seen in metaphors, with an emphasis on strong, mic-drop endings. We’ll get into details in a minute, but the exercise is simple and short:

- Begin with the sentence “I am what I am.”

- Repeat the “I am . . .” sentence structure to develop a one-paragraph self- description as seen in metaphors that incorporate multiple aspects of identity.

- Use “show, don’t tell” strategies (concrete nouns, active verbs, and sensory details).

- Don’t waste a wisp of breath on punctuation or grammatical worry.

- Finish with a strong ending or image that emphasizes an important part of your identity.

To flesh this out a little more, we begin with a planning stage. First, we instruct the students to list as many parts of their identity as they can. These might be hobbies, sports, locations, or significant events. We don’t require students to draw on any specific aspects of identity, but we encourage them to relate their writing experiences to parts of identity they find particularly influential.

Next, we model using action verbs and concrete, sensory details to tease out the intended meanings from the brainstormed lists into strong and punchy metaphors. We push a student who lists “athlete” or “basketball player” or “an optimistic person” to find far more specific images to illustrate that part of their identity: Is he a sprinter on the blocks—with an untied shoe? Or a basketball swooshing through the hoop, two seconds after the final buzzer? A rainbow after a storm?

In the face of writing fear, it’s also worth prompting students to remind themselves and others of the situations where they feel capable, even fierce. In just one paragraph, students can address aspects of their identity they worry may be overlooked or misinterpreted. They describe themselves as “the beat in the music,” the “the door holder, the how-are-you,” and the “fireman breaking down the door.” When one student wrote about the stamina needed for a full game of play on her five-member high school basketball team, “no breaks” quickly became her writing mantra as well. Especially in contexts where writers carry hard-worn stigmas of frequent mistake-making, the assignment offers a chance for students to write about themselves in a direct, powerful way.

We keep the lesson as simple as possible, since we use it as a course opener, but by its nature the assignment demands that students think within specific contexts and across contexts. Finally, students examine their lists of images and select the most important ones for their “I am what I am” assignment. Here are two student examples:

I am a White Mexican enduring the suburbs… a shook-up can of pop. I am a tidal wave gaining speed and power twenty feet from shore. I am release: the cool moist earth pressing through damp toes. I am nostalgia drifting by, begging to be seen.

—Adrienne D.

I am facing the wrong way at bat. . . I struck out without even knowing a pitch was thrown, receiving the worst grade I have ever gotten on a so-called English paper. I found I was riding a bike in a pool this whole time.

—Alex R.

We’ve used the “I am what I am” exercise in fifth-grade writing workshops, in retirement community writing groups, and in the college classroom. In just a few manageable, creative lines, writers have a chance to choose the ways they describe themselves.

Not all writers decide to reveal information that makes them as vulnerable as the student who describes how she feels in English or the student who “faces the wrong way at bat.” Many describe themselves with the hope of “a rainbow after a long heavy storm” and the resilience of the “boxer going all twelve rounds.” In the brevity of the assignment, students reveal contexts and relationships they care about. They fill in brush strokes as writers who are much more than the GPA that trails behind them or the red marks that haunt their English class memories.

Our adaptation of Romano’s “I am what I am” exercise isn’t just about identity, of course. Students get a healthy taste of “show, don’t tell” writing strategies. As they’re inviting parts of their identity onto the page, they’re reaching into the archives for specific, compelling images. Feeling lost in a crowd is an emotion worth mentioning, but writing about “intimidating letter jackets, a tangle of earbuds and smartphones, and clashing cologne vapors” is also an adult-sized step toward precise evidence selection. Like adjusting a kaleidoscope, writers explore ways that the smallest details can change meaning.

“I am what I am” is an identity-exploring prompt that can be as short as one class period or as long as three if students revise and share the statements aloud as ours do. It’s a quick exercise with big benefits for the voices it supports. We’ve seen students transform the way they talk about themselves, like the volleyball player who “tiptoed in class.” She finished her statement with the closing lines, “College, get ready. I’m coming in swinging.”

About the authors:

Karen Sheriff LeVan teaches English at Hesston College, a two-year college in central Kansas. With zeal for writing identity across the lifespan, she currently researches and writes about the struggle for words in the fifth-grade classroom, college writing culture, and older adult creative writing groups.

Marissa E. King teaches, spills coffee, and writes with students in Tulsa Public Schools. In her former role as Hesston College Education faculty and in her current studies with the fifth-graders of room 108, she wishes and works for a world where ZIP codes do not determine the quality of education.